Hubris is interesting because you get people who are often very clever, very powerful, have achieved great things, and then something goes wrong – they just don’t know when to stop – Margaret MacMillan (Canadian historian and Oxford University Professor).

[The following analysis focusses on equities for the sake of brevity, but the points made are equally relevant to Bond Index funds and ETFs].

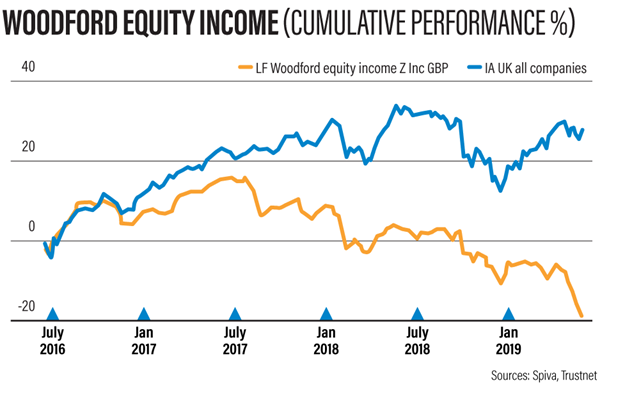

The news of the suspension of Neil Woodford’s Equity Income fund came as a shock to many investors – the immediate catalyst was Kent County Council’s decision to redeem their £250 million investment in his flagship portfolio, disappointed as they (finally) became with its performance (see above). In truth, he had little choice but to “gate” investors as the composition of the portfolio, heavily invested as it is in illiquid companies made an orderly selling off of his holdings well nigh impossible. There is a lot of blame to spread around; the FCA was, as ever, asleep at the regulatory wheel, Hargreaves Lansdown, (along with SJP), are also culpable, endlessly promoting his investment prowess, the former only removing the fund from its Wealth 50 list of recommended funds AFTER the suspension of the fund. The financial media do not come out of it well either, as they were as keen to fete Woodford as “the UK’s answer to Warren Buffett” as any broker, though they now seem to be rapidly distancing themselves from the fall-out, all claiming to have seen it coming. Last but not least, there is Woodford himself, whose strategy of investing in very small (sometimes unquoted) shares was clearly incompatible with the requirement to allow continuous trading in the fund [1]. It was a recipe for trouble, which duly arrived.

But we are where we are and for those still holding the fund, it is likely to be a long way back, though Woodford’s reputation may not survive the journey. Questions of trust are now paramount, as investors wonder whether this can happen elsewhere. Advisors (and their clients) are understandably worried.

Could this happen to EBI Portfolios? The short answer is yes, in theory – nothing has a zero-probability of occurring, but the circumstances of its happening are so unlikely as to have a negligible risk of eventuating. Here’s why:

EBI portfolios consist of two types of funds; mutual funds (OEICs and Unit Trusts) and ETFs. They are all index trackers or rules based index funds, dedicated to tracking the returns of specific Indexes, or capturing the returns of a specific factor from a revised universe of stocks within an index, which as we note below, have pre-defined limits on what can be invested in. For ETFs the same applies; in the latter case, it is normal for ETFs to continue trading, even when the underlying marketplace is closed – for example, Japan has a “Golden Week”, at the end of April every year, when the markets are shut, yet Japanese market ETFs still trade, (unlike mutual funds, which stop trading for the period – see this list of market holidays for Vanguard funds). Volumes are a little lower than normal and the spread on ETFs are a little wider, but not to any significant extent. So a transaction can always be done. It is just a matter of the price.

As Index funds/ETFs are merely tracking an Index, it makes little difference to the managers (or to an extent ourselves), where the market goes, as long as they track it closely, (as that is the job of the Index manager). There could be redemptions from investors but the fund would sell off the Index in the same proportion as the market capitalisation of the underlying holdings to maintain the fund’s exposure. For Value/Momentum ETFs any large demand for redemptions would probably lead to the ETF trading at a discount to NAV (Net Asset Value), but once the discount gets too wide, Authorised Participants (market-makers or Institutional trading desks for example) would step in and buy the ETF and sell the underlying holdings to offset their risk exposure, thus soaking up the excess selling pressure. Therefore they will almost always be a bid, it just may not be at NAV.

Assets and markets can become illiquid at times – this is a feature of markets, not a bug. But it is hugely less likely in an Index fund constituent than investing in Start-Up firms or SME loans etc [2]. It is also (theoretically) possible for an individual asset to rise such that it reaches or exceeds 20% of an Index’s total value, (which would mean that under UCITS rules it must be sold down to below that threshold). But should such an event transpire, the Index provider would most likely change the Index weightings to prevent this – it is not good for their reputation to have chaos erupt as a result of mass selling of an individual asset because it has outperformed.

What about Platforms? The assets are held by a ring-fenced Trustee company, to which neither the Platform NOR EBI have any access. Should either of these organisations fail, the assets are protected from any claim by creditors of the platform itself. So, for example, if Transact, Wealthtime or Nucleus (three of the most popular platforms with advisers using EBI) were to go out of business, they could not raid the assets of clients to pay off their debts. If EBI were to go under, the same would apply. The assets will remain owned by the clients (to which neither we nor the Platforms themselves have access) via a nominee account and all that would change would be the identity of the DFM/Platform running the portfolios. Any cash held via a platform would be covered up to the FSCS £85,000 limit (per person).

EBI Portfolios DO NOT hire “star” fund managers, we do not buy illiquid assets and we do not concentrate our portfolios. There is no guarantee that for example, the Vanguard FTSE All-Share Index unit trust or their Emerging Markets Index fund will not fall in price – they can and do from time to time. But to suspend dealing in these funds would imply a market collapse of such epic proportions that, frankly, we would all have much bigger problems on our hands. The same principle applies equally to ETFs. They both have, as part of their Index construction rules, limits on how liquid an investment must be – they MUST trade above a minimum average daily trading volume for an asset to be included in an Index (as a consequence of Index providers’ “free-float-adjusted” Index compositions). If an asset does not meet those requirements they are not included in the Index – full stop – and thus we cannot buy it even if we wished to do so, (which we wouldn’t).

Meanwhile, the arguments for Active Management are looking increasingly threadbare – Woodford has been described (repeatedly) as Britain’s equivalent to Warren Buffett (as this gushing BBC article did in 2015), but that praise has been seen to be misplaced. The confusion of skill for luck has been widespread, something that many (private) investors are beginning to realise. The idolatry will presumably move on to someone else – Nick Train (who recently bought a large amount of Hargreaves Lansdown shares prior to current events) is next in line for this role, but it is very likely that he will “blow up” in exactly the same fashion sooner or later and the whole cycle will begin once again. Plus ca change…

[1] It could be described as a liquidity mismatch; the ability of investors to redeem their holdings immediately is incompatible with the speed at which (some of) the illiquid assets could be sold. We saw exactly the same thing with the “gating” of Property funds in the aftermath of Brexit, as a run on those funds occurred much more quickly than the underlying assets (property) could be realistically liquidated. If a fund manager wishes to own illiquid assets, that is his/her prerogative, but a closed-end fund structure (i.e. an Investment Trust) ought to be more appropriate. Unfortunately, these types of funds are much less popular with investors and so limit a fund manager’s ability to grow assets.

[2] There IS a liquidity premium for investing in those sorts of assets, but for us, the risks are too high. These investments belong more correctly in Private Equity funds or other non-compliant UCITs schemes, not in open-ended funds, a reality Neil Woodford ought to have been well aware of. That he has moved a substantial proportion of the unlisted equity positions into his Patient Capital Trust vehicle suggests he does but begs the question of why he didn’t do this in the first place. He only acted once the roof was ablaze.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.