Events in Europe appear to be moving in a decidedly dangerous direction. The initial huge sympathy for the migrants has given way to concern (and in some cases alarm) amongst the local populations. From welcoming refugees unconditionally a few weeks ago, Angela Merkel has changed tack, limiting their “rights” and preventing further inflows (as far as possible). This puts them on a par with the likes of Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia and others who are actively seeking to offload the problem to others. Meanwhile the EU itself, according to the Washington Post, predicts 3 million more refugees will come to Europe by year end 2016. The almost total paralysis of leadership has created a credibility problem for the Eurozone elites. The more they point to the “positives” of immigration, the more the local populace gets worried about the effects on their already meagre economic prospects. Even some leaders expressed it: “A modern day mass migration is taking place…that could change the face of Europe’s civilization,” warned Hungarian President Viktor Orban.

This is having a profound effect on the European political landscape. No incumbents appear to be safe, as recent events in Canada and Poland attest, amid a widespread dis-enchantment with the EU – and the austerity policies that come with it. (A quick glance at the original intent of the European “project” shows that it has changed almost beyond recognition.) Europe traditionally sees protest groups coming from the Left, but the current migration issue is also the primary driver behind the rise of Nationalist/Rightist parties across the continent, as the very survival of Europe’s Judeo-Christian civilisation is seen to be at risk. If you doubt this thesis, we are told, look no further than the fate of the North American Indians…

One of the most important factors in the success of any polity, is the concept of consent. In order to comply, the population must be convinced of the right of the rulers to rule. The following chart suggests that this consent is in the process of being withdrawn.

One very practical expression of this discontent with the Establishments of Europe is the rise of separatism. The election of Syriza in Greece began the process (which we covered here), but the continuation of austerity and the subsequent huge (youth) unemployment rates have taken their toll on support for the European “project” – and, to a large extent, Syriza itself. Eight of the top ten OECD nations with the highest youth joblessness are EU states. The rise of Pademos in Spain, UKIP in the UK, the Northern League in Italy, along with the political advancement of separatism (in Scotland), has created an extremely volatile political environment.

Recent events in Portugal, where the President refused to allow a socialist-led coalition to form a government, despite them having won an election, has fed the impression of an elite attempting to void unfavourable democratic results. After the socialists voted down the resulting minority government and formed an agreement with communists and the Left Bloc, it appears that a potential downgrade to the country’s bonds would lead to the ECB refusing to buy Portuguese debt, thereby using the same threats that (seemed) to work with Greece.

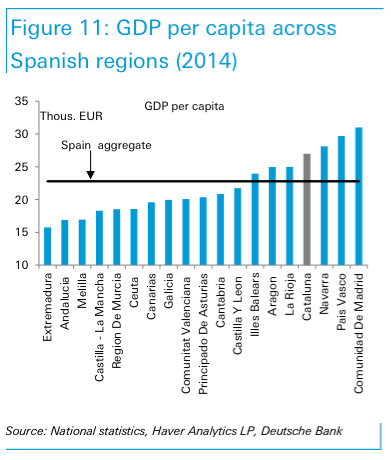

Meanwhile in Spain, the Catalans have now begun the process of secession from Madrid rule, with a view to a referendum on full independence in 2017. The Guardian reports that this has not gone down well in Madrid, with Prime Minister Rajoy responding quickly: “I’ve said it continuously and I reiterate it today – the government will not allow this to continue,” said Rajoy, “Catalonia will not disconnect itself from anywhere, and there will be no fracture”(1). The constitutional court is likely to quash the effect of the Catalan resolution on independence, but it is not clear that they can physically stop the process. Catalonia accounts for nearly 20% of Spanish GDP (see chart below), so this would have profound implications for Debt:GDP ratios. This brings the troika back into play, potentially facing an anti austerity alliance between Spain and Portugal. It may be more difficult to put so much pressure on two parties than on one (as happened to Alexis Tsipras). Indeed, with Spanish elections due on 20th December, the stakes are high and getting higher – Article 155 of the Spanish Constitution allows the national government to over-ride the authority, and even cut off the funding of recalcitrant regional governments. Too robust an approach from Rajoy may however merely lead to even more support for the separatist cause. This could be the political equivalent of an “El Clasico”(2), but even more bitter. The lessons from the Scottish referendum seems to be that once out of the bottle, the separatist genie is impossible to put back in.

What does this mean for markets? The main change that these events may engender is that the concept of political risk is now back on the agenda for the first time, for at least since the Greek crisis erupted, and possibly longer. The problem for the central banks is that they cannot intervene to remove this risk – indeed, the more they intervene, the worse it could become. This has an effect on asset pricing – if we now have to factor in the possibility of political unrest (as a result of opposition to austerity policies for example), bond yields will rise, possibly sharply. At the very least interest rate spreads between Eurozone countries will widen sharply. This effect will be felt most acutely at the longer maturity range (this Bloomberg page shows Euro bond yields. Compare these rates with Eurozone inflation rates since 2000. The average Euro inflation rate since 2012 is 1.07%, which implies less than 1% term premium for both Spain and Italy (0.78% and 0.58% respectively). This disaggregation of the components of a bond yield demonstrate that there is little room for political risk in current yields. The effects could be quite dramatic – if we take the currents yields as the discount rate, the Spanish bond price would fall 9.31% and the Italian version by 9.32% if one added just 1% political risk premium to the required rate of return for a zero coupon bond*. This would have the effect of wiping out several years worth of yield in one fell swoop. Of course, stocks have a duration too**, and it is a generally higher (since stocks are viewed as an asset with near infinite maturity). Thus the effect would be still greater.

How to deal with this?

1) Diversification (obviously). The greater the variety of bonds held (by issuer/region etc), the lower the risk of this factor affecting all bond holdings. A global portfolio has a much better chance of withstanding the dangers of upheaval in Europe.

2) Shorten duration/maturity: EBI Bond holdings have an average maturity of 5.38 years and an average duration of 4.7 years. This means that political risk is mitigated (and any rise in yields caused by this factor can be captured relatively quickly).

3) Accept it – most political risk occurs without warning. If this were not the case, the market would already have “priced it in”. On the other hand, it is an extra premium waiting to be picked up: the electorate may be in a very bad mood at the moment, but it won’t last long as memories tend to be short. That creates opportunity as well as risk…

* If required I can go through these calculations in greater depth, to show how these numbers are arrived at – please get in touch.

** It is approximated by the price to dividend ratio: an index at 100 paying out a dividend of 3 would have a duration of 33.33 (100/3=33.33). All else equal, as with bonds, the higher the dividend (or coupon), the lower the duration.

(1) This has led to several commentators referring to the Eurozone as a Hotel California: “you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.”

(2) The twice annual derby between Real Madrid and Barcelona – occasionally, during the fights, a football match breaks out!

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.