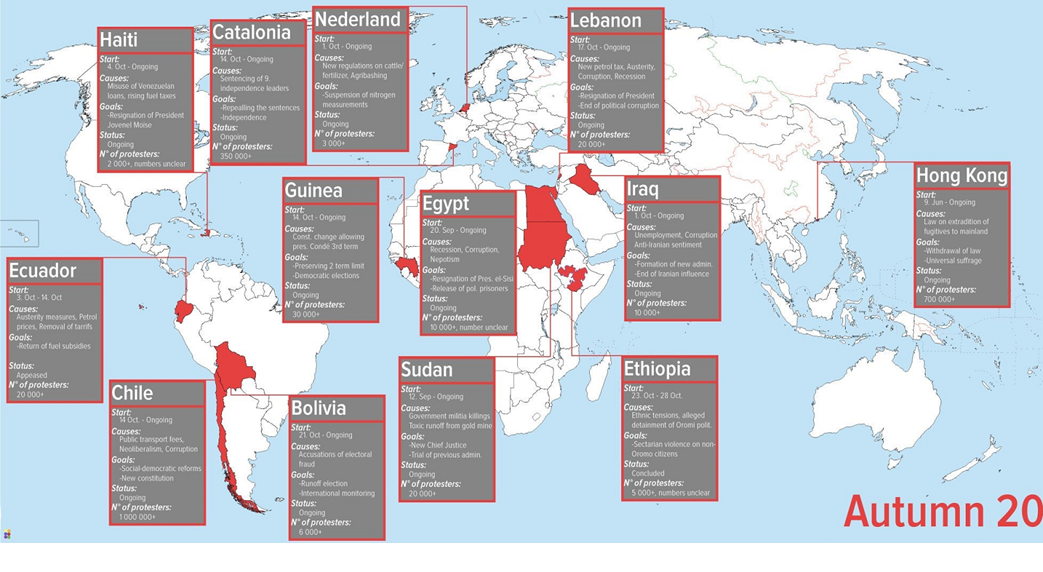

More than two years ago, we discussed the rise in social unrest across the globe as nations start to split apart. This has got much worse since then and it appears to have become generalised as the cleavage between populations has now spread to families. Why now and how will it all end?

Traditionally, it is an economic downtrend that initiates the trouble. Throughout history, revolutions have occurred amidst widespread financial stress. But with asset markets at (or extremely close to) all-time highs, this is clearly not the case at present [1]. In such diverse nations as France, Spain, Algeria, Lebanon, Hong Kong, Chile and Bolivia popular unrest has already claimed political victims. (For the sake of brevity, I will ignore, for now at least, the tensions unleashed in the US and the UK – they have not yet spilled over into violence; it is noteworthy however that in Germany, a recent regional election, Die Linke, a far-left party, won the state election in Thuringia, with the AFD (a far right party) second. Between them, they garnered over 54% of the total votes cast- as none of the centrist parties will deal with them it matters not, but it is quite a vote against the establishment political parties).

It is all starting to resemble the late 1960’s; as the level of discontent rises, demonstrations across the globe get more violent, which is course guaranteed to make the nightly news channels. Most of these countries have little in common- except maybe one thing. A popular revolt against the perceived corruption of the political classes, who appear untroubled by the day-to-day concerns and hardships experienced by the general populace. The well-off elites appear deaf to the impact of austerity, neo-liberalism etc. on standards of living experienced by many, inevitably leading to discontent, which then leads to unrest, as wealth inequality widens inexorably. Most recently, the Iranian government have announced that petrol prices would rise by 50%, as the government cut subsidies and introduced rationing. Presumably, the authorities wanted the blame to price rises on US sanctions, but as this BBC article suggests, the population are not buying it. Amnesty International have reported at least 100 deaths, but the government’s decision to cut off the internet makes accurate reporting difficult – it may be far higher than that. One is forced to wonder what the Iranian government imagined the response would be – the US attempts to enforce “regime change” in Iran have failed dismally over the years, but it is possible that the Clerical elite in Iran might just manage it themselves…

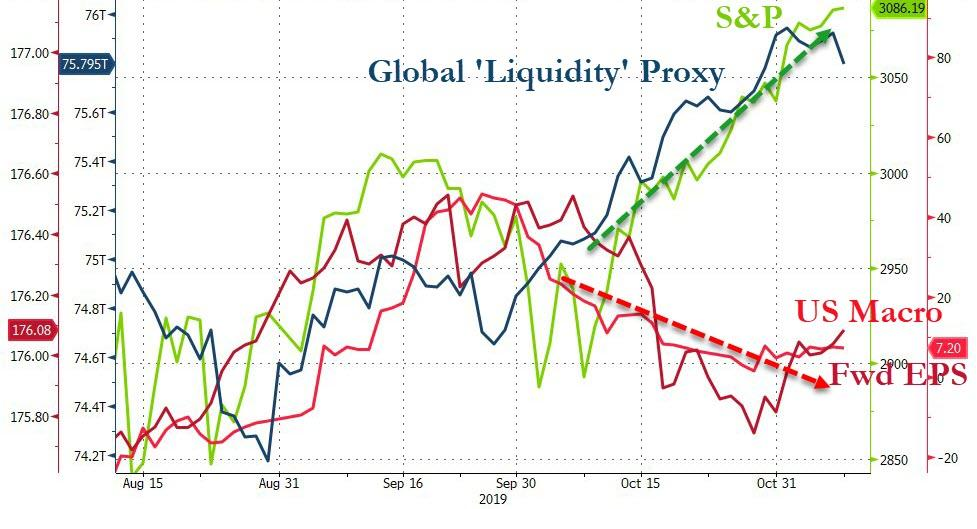

For the moment, markets have careened serenely on upwards, (helped by the Fed’s liquidity injections, totaling $280 billion in just 10 weeks. US markets have risen almost uninterrupted over this time, in contrast to markets more directly affected by the worldwide tumult (see below). Lebanese bonds at one stage last week reached 100%, as investors panicked.

This torrent of liquidity has pushed up US equity markets, despite the deteriorating economic fundamentals, as market continue to react in a Pavlovian fashion to cash injections, either via Repos, or outright QE operations.

But can this continue? The short answer is yes, but it may not do so, particularly as elections in both the UK and the US approach. Opinion polls are often wrong, but are currently pointing to both Boris Johnson in the UK and Donald Trump emerging victorious; should this change in either country, markets are likely to react negatively. In the short term, however, first of all nervousness will probably rise as the dates near.

What can an investor do? In truth, nothing. There are far too many uncertainites to deal with and acting at this point risks making returns worse, not better. The key is diversification. Neither the results of elections nor the response of markets to them are predictable, as both Trump’s victory and the Brexit vote have conclusively demonstrated. Stick to what you have in terms of asset allocation and preferably do not look too often at one’s portfolio. The danger lies in seeing what one wants to see – wishful thinking – alongside overconfidence, whereby we over-rate our ability to see into the future (or even see the present in some cases).

Things may get more volatile in markets, but the odds of successfully buying or selling in good time are vanishingly small, to the point that it is not worth the effort. The best (and realistically only) course is to wait and see what happens. As long as one has not taken a “view” on election results, there is much less to fear that meets the eye. An asset allocation that suits the investor’s time horizon and risk appetite will serve an investor far better than any amount of portfolio tinkering (and will end being cheaper). That is the main purpose of owning bonds – to reduce the risks associated with equity market volatility. A 100% equity content portfolio implies an acceptance of this potential volatility. This may suit many investors, but far fewer than the number of those who think they can live with it ex-ante.

Markets are far more resilient than they are given credit for (forecasts of a “crash” imply an inability of investment actors to process information accurately and in a timely manner). Several decades of price action shows this to be untrue, which is why major market declines are so rare. Betting on one is thus taking the wrong side of history…

[1] If one believes that the stock market IS the economy, that is.