A fanatic is one who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject.

OK, I know I have covered this before (here), but in the cacophony of market forecasts arising from the brokerage industry, and dutifully repeated by the financial media, I feel the need to purge myself of the temptation to listen to them. (This may be a form of therapy – bear with me.)

We know that the experts get it wrong with monotonous regularity. Last year’s forecasts (and somewhat lurid headlines), kept investors constantly on alert for the bond market rout that never occurred, and in the UK the rate rise that never happened (as we said here in July). Meanwhile, having been completely wrong about the direction of US equities in 2015 has not prevented strategists from being resolutely (and uniformly) bullish about the prospects for 2016 (with one exception). This hyper-optimism can be seen in the area of economic forecasting too, with Bank of America getting it badly wrong on a one year GDP prediction, but seemingly able to see no recession over the next 10 years !

The more important question may be why the predictions are so wrong. Could there be a structural reason for their inaccuracy?

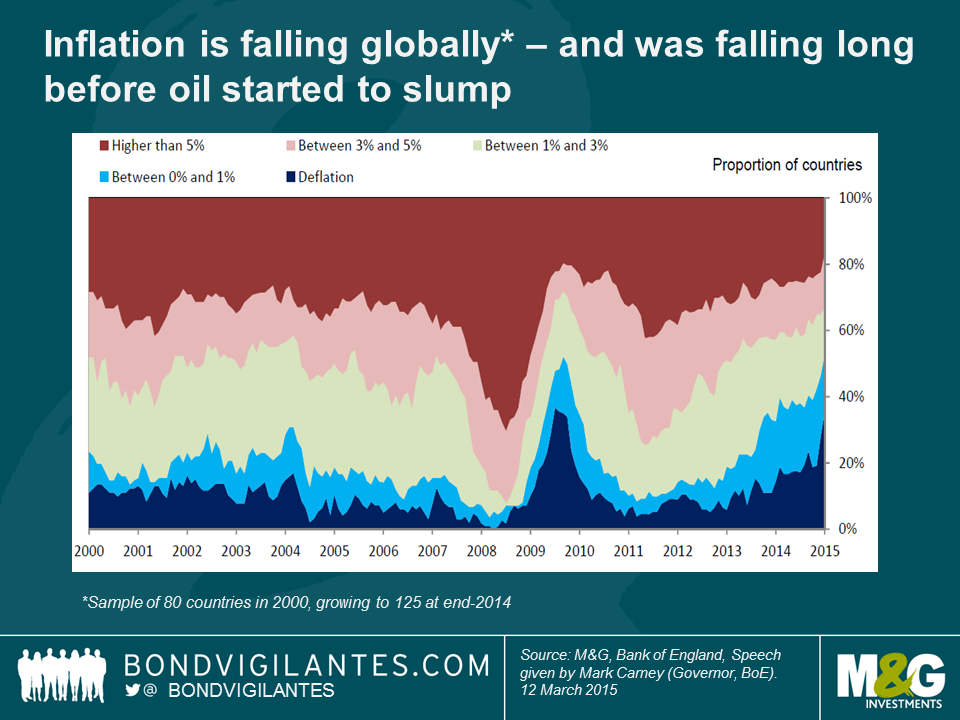

One of the striking things about the economics “industry” (for that is what it really is) is the uniformity of method. There are no significant differences of opinion concerning the framework within which analysis is undertaken. Since the Central Banks undertook QE as a policy tool, there has been a general expectation that it would lead to higher inflation. (Indeed , it was one of the Fed’s implicit aims.) The Bank of England also justified their QE programme in similar terms, to wit, “Without that extra spending in the economy generated by QE, the MPC thought that inflation would be more likely in the medium term to undershoot the target” . In reality, it had a major effect on asset inflation, but no impact on Global Inflation (or Growth) levels, as the following chart demonstrates.

Only in the last year or so has the realisation dawned that QE has had the opposite effect. This article was an early example of the genre, explaining that the lack of “creative destruction” leads to overproduction, oversupply and thus lower prices. This can be seen most obviously in the oil market, where brokers are now competing with each other to call ever lower prices, as OPEC countries continue to overproduce. With negative interest rates now widespread across Europe, even more bizarre scenarios are now unfolding.

Until recently, the name Hyman Minsky would have elicited blank faces. But his views came to prominence after the 2007-09 financial crisis. He promulgated the “Financial Instability thesis” (1), whereby attempts by the authorities to promote stability only lead to ever greater excesses, as market participants react to lower perceived risk, by taking still greater risks. This is a form of “risk compensation” (in the same way that car accidents do not decline as a result of the wearing of seatbelts -indeed, it is possible that the opposite occurs). Markets unfettered by regulatory constraints ultimately arrive at the same destination as those which are regulated, and thus stable, albeit by a different route. The process culminates in a “minsky moment“, whereby the long period of prosperity and asset price rises lead to excessive leverage and speculation. Once the cash flow generated by these assets is no longer sufficient to pay off debts acquired to own them, losses are made on these investments, which leads to a collapse in asset values as investors are forced to sell into a market with no bids. A sharp price (and liquidity) slump duly occurs.

The problem is, as this blog points out, is that prior to the financial crisis, “Mainstream DSGE (2) models in use in 2008 ruled out the very possibility of a crisis, whereas Minsky believed in their inevitability in some shape”. I remember clearly analysts’ (and my then-employer’s CEO) refusing to contemplate the possibility of a market downturn in 2000, which points to either 1. a refusal to accept reality or 2. vested interests. I have quoted Upton Sinclair before, but nowhere is it more true than in economics and markets, where people cling to theories long after they have been disproved in practise. Minsky died in 1996, thus not witnessing the seeming validation of his analysis, but his effect on central bank policy making has been surprisingly slight. Why?

Mainstream economists and strategists tend to “herd” in the same way as investors do, as getting a forecast wrong on one’s own can signal inability, or, as Keynes stated “Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.” The cost of being wrong alone is too high for most to be willing to take the career risk, so they hug the consensus position. The widespread use of similar models, assumptions and tools used to analyse the economy and markets, (for example regarding rational, frictionless markets) bear little resemblance to the real world. Market returns are as much a function of sentiment (or emotions) as logic (or “fundamentals”), which they cannot model. In this sense, it may be unrealistic to expect accuracy, but then why do they continue making predictions ?

The obvious answer is that it feels good – the prognosticator gets to fold forth, thereby stroking his (and it is usually a man) ego, whilst the listener is soothed by the authority of the speaker (and can justify their investment errors by pointing to the recommendation as being rational and sensible at the time). Humans have a need to believe, and as part of the bargain, we ignore the fact that the forecasts are consistently wrong. This of course is easier to do when it is not your own money that is being invested – fund managers have a different agenda to that of their clients. Forecasters forecasters are in business, of course, and so motivating trades from investors also features as part of their job description. Brokers are paid according to the volume of trades executed and not the value that they create thereby.

None of the last paragraph benefits the investor; indeed it is strongly against their interests to allocate funds in this way, but many do, mainly because the financial media tells them this is the way it is done. But the viewing figures for financial TV have been in decline for a long time, which suggests viewers at least are alive to the scam, as does the continued flow of funds out of actively managed funds and into index funds. This is likely to be a long term trend.

(1) See Biography.

(2) Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.