“Most people would sooner die than think; in fact, they do so.” ― Bertrand Russell (UK writer, historian).

Steve Forbes (of Forbes magazine fame) once said (apparently) that you make more selling advice than following it. “It’s one of the things we count on in our business, along with the short memory of our readers”. An article I recently read (in Forbes, ironically), suggests that this continues to be the case. It once again takes the line that there are alternatives to Indexing, and that Dividend investing is the answer. Let’s look under the bonnet to see how it arrives at its conclusion.

The article begins by highlighting the low yields on offer in S&P 500 ETF’s (currently around 2%). It then informs us that a drop in prices will wipe out the yield, and follows up with the revelation that the Fed may raise rates in December, pointing to a fund paying a 7% dividend, at a discount to Net Asset Value as the alternative to owning the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO). This fund is called the Nuveen S&P Overwrite fund (code SPXX), which sells call options on its stock holdings to provide an income for fund holders. A long as the share price does not go above the option’s strike price, the fund gets to keep the premiums received for the option, and this serves as additional income for shareholders.

There are a number of in-built assumptions with this recommendation:

1) Stock prices are currently “precarious” according to the author; a US rate rise will lead to selling of shares and buying of bonds. Thus, one should not own an Index fund, which would obviously fall in that scenario.

2) It is possible to increase income yields with no effect on the Investor’s risk profile. If 2% “isn’t going to cut it for most retirees”, then this fund will do the trick. After all, a 10% fall in the market will wipe out an amount equivalent to five times the annual yield of the Index fund.

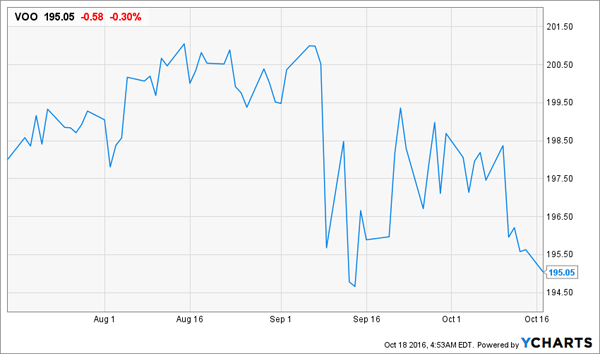

The charts below show the relative price performance of the two choices (these are ones he uses – we shall gloss over the rather short term nature of this information).

.png)

It sounds superficially plausible, but it contains some problematic assertions, which we shall address in turn.

1) In what way are stocks “precarious”? The notion of rates rise = stocks fall is far too simplistic. Unanticipated rate rises may cause stock price declines, but the history of the last 10 years is that Central Banks take enormous care NOT to surprise markets (as if the latter has some sort of veto over the former’s decisions):

The Fed raised US interest rates in December 2015, and the Dow fell -2.77% on the day of the announcement. But one week later it was up from the point of the rate rise. US Treasury bonds were up nearly 1.5% in the same period. The speculation regarding the next rate rise in the US (now expected to be in December 2016), has been on-going for so long now that markets ought to have discounted that event also.

If markets were to fall, Index funds would surely do likewise; but the charts above show that it may not support the investment thesis. Taking the performance from the early September (8th) respective peaks, the Vanguard Index ETF was down -2.96%, but the suggested alternative fell by -6.2% in the corresponding period. So, this Fund (code SPXX) provided no downside protection whatsoever. Over a 5-year horizon, the situation is even worse; 5-year annualised returns for SPXX is 2.31% (+7% yield), compared to VOO, which has returned 10.8% p.a. (+12.8% if one includes a 2% yield). So, contrary to the assertion made in the article, the fund does not out-perform in either downturns OR up-trends. This is quite easy to reconcile – in a downtrend, the discount to NAV widens, as investors become more cautious generally, whilst in an up-trend, the fund loses money on its’ call options (as the shares rise in price), offsetting at least some of the capital gains made. In summary, the fund participates in ALL of the market’s fall, but only around 75% of the corresponding gains – surely a lose-lose proposition in risk-adjusted terms.

2) The advent of QE has lowered risk-free rates of return, leading investors to look for yield, but implicit in the income strategy is that capital gains are taken as read. In reality, risk, to paraphrase the law of conservation of energy, remains constant – it is merely converted (into something else). An increased yield comes at the cost of risk to capital, or as shown above, in lower expected returns. A higher yield now would mean lower returns later since total returns are a function of both Income and Capital Gain. A higher level of one inevitably means a lower level of the other – anyone who says otherwise is fooling us (and themselves).

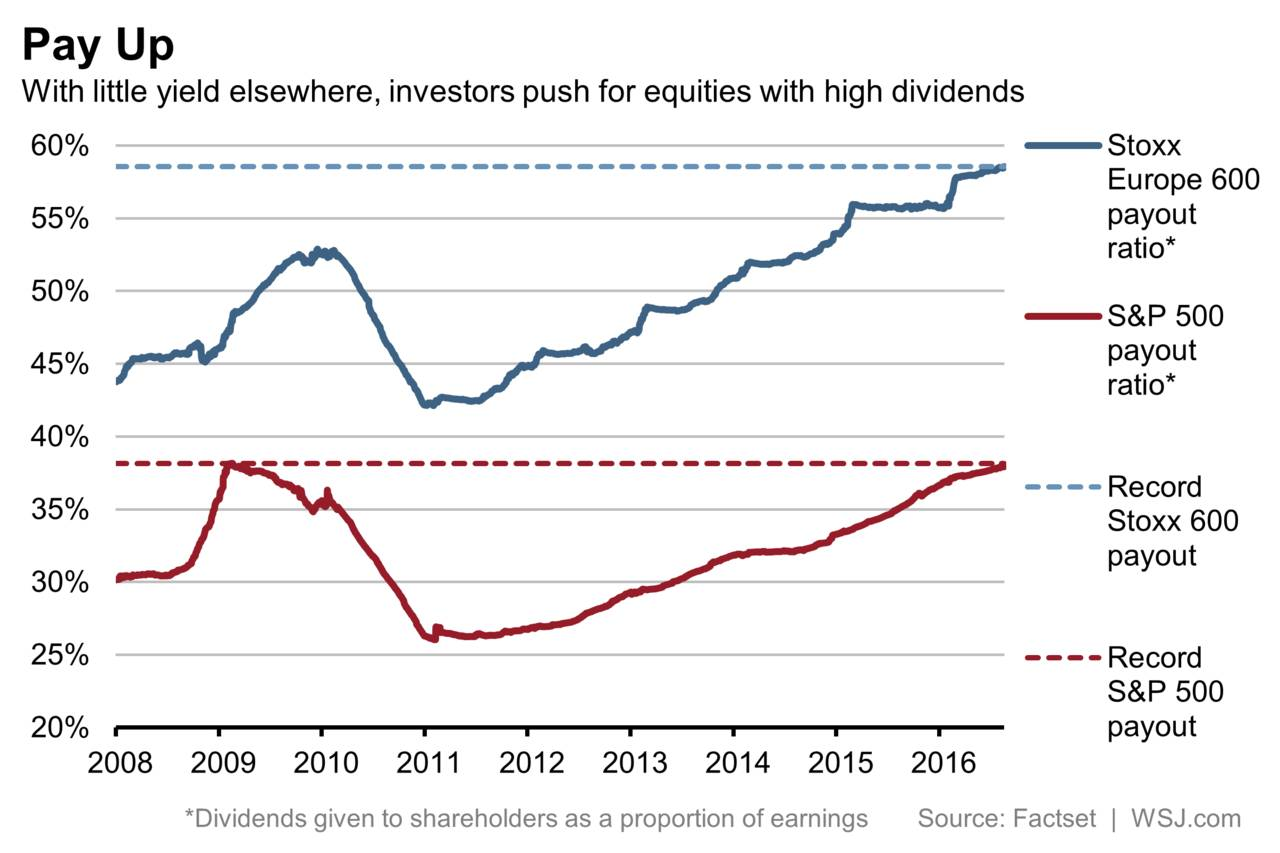

The argument contains some huge assumptions, such as “buying on dips means huge upside”, he notes the “divergence” between the prices of the two funds, believing that SPXX “will revert to VOO’s trend line” – why? Is it “inevitable”? If so, wouldn’t much cleverer investors than us have already bought it? We are left to wonder… According to the article, “regular payout increases of 12% will boost yield on initial capital to 12% in a dozen years”, but again the inevitability of this is not questioned. (Increasing dividends lowers future growth rates, because it reduces capital availability for future growth opportunities, leading to less ability to fund future payouts, making it a zero sum gain in aggregate. The chart below suggests we are close to that tipping point once again both in the US and Europe).

The article itself does mention fees but seems to almost completely dismiss their impact. At 0.92% the fund is, as he admits, 18 x more expensive than the Vanguard alternative. (Mr Owens: it “sounds like a very big difference” because it is!). He asserts that “most investors don’t even notice the fees at all”, but we do and, judging by the latest fund flow data, so increasingly do other investors. The Year-to-Date returns shows a differential of 2.85% between the two funds, which is way above the fee discrepancy, in turn, implying that they (the fees) affect short-term returns too. Apparently, if “we” had bought during the February “jitters”, “we” would have made 3%+, but how many investors actually DID so? Very few (of course if many had, the low would have occurred BEFORE February). Judging by this post, he didn’t either [1]. I can find none of his previous postings that talked of this trade idea, which makes one wonder if he had it then (as opposed to now).

The premise of this and other articles seems to be that you can have it all – high yield, low risk, price appreciation in one easy step. The above suggests otherwise. It is amazing how few millionaire investor-journalists there are out there; as with Academics (see the history of LTCM), it seems much easier to propose strategies that should work in theory, than to actually make them work in practice. At the end of the article, it says “disclosure: none”; if he had positions in this fund, he would have to declare it – that he doesn’t suggest he is not invested this way himself. If he doesn’t believe in the strategy, it is not clear why investors should either…

If investing had a silver bullet, someone would have found it by now, but there is no sign of the de-coupling between risk and reward that is implicit in this article. If it looks too good to be true, it probably is. Investors would do well to constantly remind themselves of this, else they find themselves in products and strategies that they later regret. The odds are massively against out-performing an Index – according to Dalbar Inc, just 3% of money managers beat the S&P 500 over a 20 year period. It is not obvious why this journalist/pundit is going to be one of them, and so far, his (free) recommendation appears to be worth exactly what we paid for it, and by the time that this “trade” goes haywire, he will presumably have found another “big idea” that just cannot lose..

[1] The 4 recommendations made in this article have 2 gains and 2 losses contained therein: overall, investors might consider flipping a coin, rather than adopting this strategy to save time.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.