The phrase above dates back from John Maynard Keynes’ book, “A Tract on Monetary Reform” written in 1923. Since then, debate has turned on whether Gold is a store of value or just another commodity. Until recently, however, the debate looked settled; the price has spent nearly a decade going down from a high above $2,000 to around $1,100 in December 2015 [1]. Still, the “Gold bugs” kept the faith, continuing to warn of impending disaster (notwithstanding the failure of those disasters to actually happen). In the last few weeks, it appears that they may be getting their day in the sun. Last year, it was among the better performers, losing only around 2% in US Dollar terms and it’s up nearly 10% so far in 2019 – many investors are now starting to re-assess their views. Analysts are getting bullish, as indeed are Central Banks – Russia, for example, has 2,183 tons of gold held in their reserves, up from 600 tons in 2009. But Chinese, Iranian and Turkish CBs are also increasing their holdings of Gold – not coincidentally, all of these are currently in dispute with the US in one way or another, so it might merely be a currency hedge of some sort. But the IMF too has recently reversed its longstanding Gold sales policy and they are not (yet) in conflict with Donald Trump.

Why? Because it looks like a currency war is about to break out (openly that is, rather than the tacit version we have seen for the last decade). In a series of increasingly angry tweets, Donald Trump has attacked both the Chinese and the Europeans for playing the “currency manipulation game” and urged that the US should do the same to avoid “being the dummies who sit back and politely watch as other countries continue to play their games — as they have for so many years.”

[It must be noted that Currency Manipulation is an irregular verb, conjugated thusly;

* I am cutting interest rates

* You are trying to achieve a competitive devaluation

* He/she/it is manipulating their currency to obtain an unfair advantage].

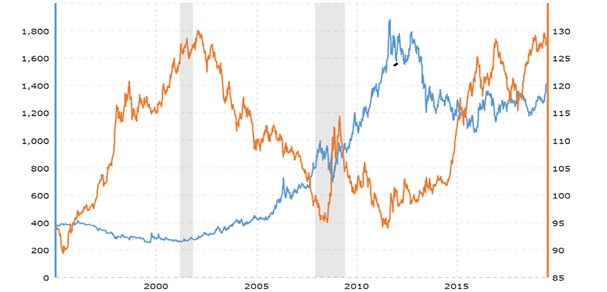

As Gold is priced in US Dollars, it tends to move inversely with the US currency, meaning that if investors believe that the Dollar will drop, Gold will rise (all else equal). Since the end of May, it has risen by 11%, as speculation has focussed on the prospects for Dollar depreciation, though only a little decline in the Dollar has occurred yet. Herein lies the problem for investors – the relationship between the two is not constant, as the next chart shows – in fact, it can be inverse. As such, there is not much correlation with subsequent inflation either [2].

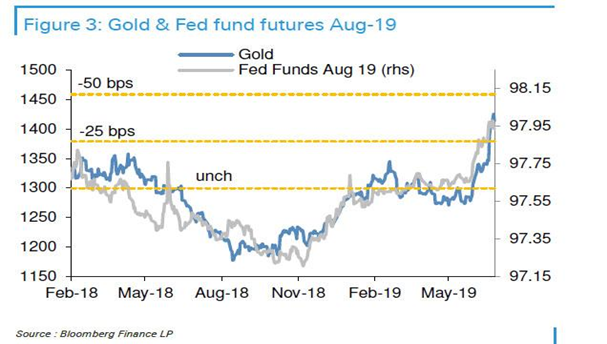

Another problem comes with how to value Gold – as there is no interest accrued by holders, we cannot use Discounted Cashflow, Dividend Discount or any other conventional financial analysis. The best we can do is to compare it to prevailing interest rates. As the chart below shows, the link has been quite close in recent years, but again, it is NOT constant. IF the current relationship holds, the lower interest rates go, the more attractive Gold becomes…presumably.

Putting these two (sometimes contradictory) factors together, it does appear that Gold is an investment asset much like all the others with time-varying drivers to returns. But it may serve as a confidence indicator – after all, why buy gold if you have no concerns vis-a-vis the economy or the credibility of the political/financial system? With the Fed seemingly ready to cut interest rates by up to 0.5% at their next meeting at the end of July at the same time as the S&P 500 is making all-time highs, either they know something that the rest of us mortals do not, or they are targeting asset prices (which is outside of their direct mandate). Neither of which is a good sign.

As it pays no interest, Gold’s performance relies on both a Dollar fall (which is by no means assured) and a new buyer to take the asset off one’s hands, as interest rates fall even further. To take the depreciation issue first, notwithstanding Trump’s (justified) complaints with regard to Europe, China, and Japan, how will the US Dollar devalue? Will the other Central Banks acquiesce in this and allow their currencies to rise? Not a chance. They will continue to “stealth” de-value all the way to the bottom if necessary to “protect” their economies – the only way Gold benefits is if ALL nations devalue in terms of the commodity itself and it is not clear how that helps them. The second factor driving returns (lower interest rates) is linked to the first – should investors decide that rates are too low, and need to rise, the Dollar would (possibly) gain, wiping out the effect of the first positive driver. It thus seems that a long Gold position is akin to a wager on BOTH a lower dollar AND lower (forever?) interest rates.

The final issue is how to accommodate it in one’s portfolio. If it is being employed for inflation protection purposes, it could be argued that equities, (providing they have “pricing power”), do the job just as well and (should) have a dividend yield as well, while one waits for the cashflows to arrive. If it is attractive due to low interest rates, one is effectively buying a bond proxy, which would presumably fall in value in the same way as a bond if interest rates rise and is thus not a hedge in a meaningful sense. If one is betting on the stupidity of central bankers and politicians (a regular event one might say), the exposure would need to be high enough to offset the potential damage to other asset classes, which in turn would drag on overall portfolio performance should these events NOT come to pass. What asset class would one sacrifice to include it? It is by no means a clear cut decision and as such we would probably pass on it. It may well be useful as a short-term trading vehicle, but for long term investors such as ourselves, it holds little appeal.

[1] I remember the low point in 2001 as Gordon Brown (the then UK Chancellor of the Exchequer) decided to sell over 400 tonnes of Gold, reaping an average price of around $275 per ounce). I remember because I bought some from him – one of the very few examples of the government actually helping the citizenry.

[2] If you are interested in playing with the numbers, there is an inflation-adjusted returns calculator for Gold available (here). Since the low point in April 2001, Gold has seen an annualised (inflation-adjusted) return of 7% per annum – around the long term return for equities since the early 1900’s – but a per annum loss of 4.27% pa. since the August 2011 highs. So, as with all asset classes, it does depend on when one buys it.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.