“The key issue is the shift of the centre of gravity from the West to the East, the rise of China and India” – Klaus Schwab. (Chairman of the World Economic Forum).

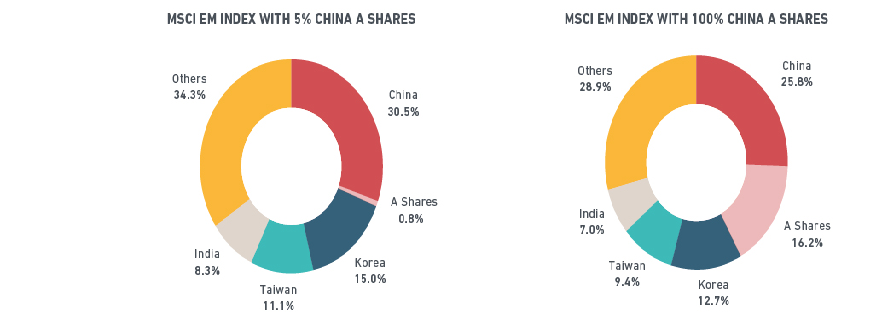

After a long period of vacillation, (which began in 2013), MSCI announced in June last year that Chinese “A” shares [1] will be included in their Emerging Markets Index, in a two-stage process, starting in June this year and again in September. It has been a tortuous process, but it could have massive “flow” effects. Inclusion in the Index at just a 5% weighting could lead to $22 billion inflows into these 226 large cap Chinese A shares because as of December 2017, $13.9 trillion is benchmarked to MSCI Indices globally. As the chart below shows, however, if market liberalisation warrants full inclusion, Chinese shares would represent 42% of the total Emerging Markets Index, with A shares alone constituting 16.2% of that amount – (if Mid Cap shares were also added, nearly 50% of the entire EM Index would be in Chinese firms though this may be jumping ahead a little). Analysts expect further inclusions to follow.

According to State Street Global Advisors, a 0.8% weightings rise in Chinese shares would give rise to an ex-ante tracking error of 0.1% vis-a-vis the EM Index (if none were bought) – the changes would see the maximum overweights of around 1% in IT and c.-1% in Financials, Some 50 or so of the new entrants to the Index also have H share listings, which could just be overweighted in the same proportion of the A-share weightings. Doing this reduces the potential tracking error to around 0.08%, but as the weightings of A shares rise, the effectiveness of this policy is reduced. For now, though, with brokerage and custody charges being higher than those in the West combined with the fees involved gaining QFII regulatory approval to buy these shares directly, the costs appear to be higher than the potential tracking error risk.

But this will not last forever; how quickly this changes is to a large extent dependent on the next steps. As they reach 100% IIF (Index Inclusion Factor), their weighting in the EM Index will rise to 16% and a country that represents around 17% of Global GDP, 11% of Global trade and 9% of Global consumption (but just 3.9% of the MSCI All Countries World Index ), cannot be ignored, (even if we DO ignore their growing political clout). Go forward 20 years (and assume some progress on market opening/democracy etc.) and there is no reason why China could not become a Developed Market subject to the caveats mentioned above, (though with the state of Western markets and economies at present they may want to reconsider that ambition). But politics (as well as trade) often gets in the way of economic progress, so this may require a sea-change in attitudes.

The process of inclusion is complicated by the fact that there are (at least) 3 Index providers (MSCI, FTSE Russell and S&P), all of which have different eligibility criteria [2] and re-constitution periods, such that not all Index providers’ benchmarks are created equal. They tend to focus on 3 main areas – 1) the stage of economic development, using a GNI (Gross National Income) per capita measure, 2) Size and Liquidity minimums (the members of the Index must be of sufficient market capitalisation and must be investable – if there are no shares available to buy, the constituent firm becomes uninvestable), and 3) there must be significant openness to foreign investment – and the ability to get out of the market should the investor wish to do so (so capital controls are very much frowned upon). Other factors would include legal and regulatory frameworks that enable investors to have confidence that their rights can be (and will be) enforced, which is where China has hitherto fallen foul of the Index providers – it is not clear that many of these issues have changed for the good, which leaves the impression that the decision was prompted by incentives that may not be entirely divorced from realpolitik.

Thus, one can have potential oddities, such as the fact that South Korea is still an Emerging Market (according to MSCI), whereas it moved to Developed status in 2009 in the FTSE Indices, and that Israel is no longer one; in the former case, currency controls are still in place (justifiably one might think, given the recent declines in Turkey, Argentina, and Brazil), but it also judged to be relatively corrupt, (worse than that of China) and the chaebols (South Korean conglomerates) behave in ways that might make RBS’s GRG blush. In the case of Israel, it does not appear to be as corrupt, has a per capita GDP around 30% above that of both Korea and Taiwan and is much more foreign investor friendly. (The stated reason for its inclusion in 2009 was the decision to abandon “geopolitical risk” as a factor, which would possibly exclude South Korea now also if it were still one of the criteria for Developed market status).

This would have implications for Institutional investors; if China is more heavily weighted in the Benchmark, there is less of everything else. (see above pie chart). It also means that there will be deviations of returns between the 3 Indices; only the MSCI Index has Korea in it, the consequence of which is that the MSCI weighting to India, South Africa, and Brazil, for example, are 3-4 percentage points lower in MSCI compared to the other two Indices. One could argue that a “purer” exposure to EM would be achieved away from the MSCI Index, (but the corollary is that any fund expecting EM to do less well might be inclined – if they were trying to “game the system” – to benchmark themselves against the MSCI Index instead. Heaven forfend that an Active Manager might think of doing such a thing! In any event, the risks of investing in any one of these Indices are markedly different, which requires a careful analysis when fund managers declare themselves “outperformers versus their Benchmark”.

What does this mean for EBI and its EM weightings? Not much really – Vanguard’s EM Index fund has already incorporated the change in their fund that we own and the iShares EM Index fund has done likewise (albeit at differing weights, due to the differing benchmarks being used to measure returns). Despite the above analysis, State Street have also chosen to raise their weightings in China (via their ETF) to match the Index too, so it appears much of the re-balancing has already happened.

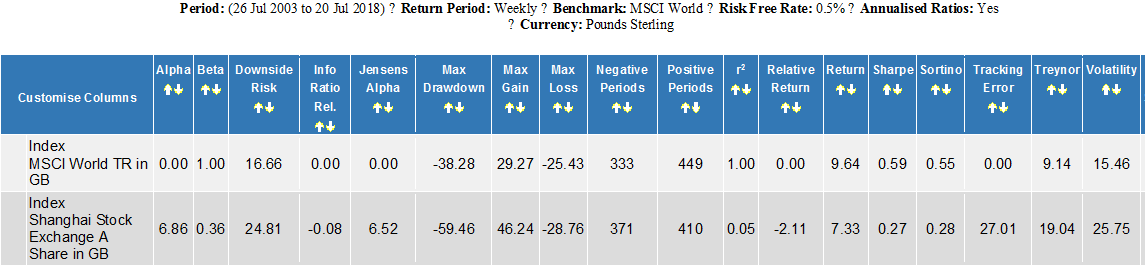

As their weightings in China rise, therefore, so will ours; what happens next will be a function of the Chinese state’s attitude towards adapting their markets to global standards, which will inevitably take time. But we are invested in Emerging Markets for the long haul and the extra diversification benefits of owning shares that were previuosly inaccessible is obviously a good thing. It has been a wild ride though, (as seen below) and is definately not for the faint of heart…

[1] A shares are a distinct class of shares; this pdf gives an overview of the different share classes available in China. Previously, A shares only were only available to Chinese residents or “Qualified” Institutional Investors (QFII). B and H shares could be traded more freely.

[2] See here for the FTSE, the MSCI and the S&P EM methodologies used to decide inclusion in their respective Indices.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.