FT Adviser article ‘How to Understand Factor Investing’ Click here to undertake CPD.

Factors Introduction; Quality and Minimum Volatility

Factor investing can be a challenging topic to navigate. With an alphabet soup of terms and explanations, it’s easy to lose sight of the bigger picture when seeking to understand what’s behind a factor-based investment approach. In this article, the first in a three-part series, we hope to shine a light on factor investing, explaining some of the history, key concepts, and drivers behind this investment style.

Put simply, factor investing is an investment approach that involves targeting quantifiable characteristics or ‘factors’ that can explain differences in security returns. A factor-based investment strategy will tilt a portfolio towards or away from specific factors, seeking to harness favourable characteristics in order to generate additional return, or reduce risk, in comparison to the wider market.

Factors are a set of properties common to a broad set of securities, and a factor-based strategy will typically approach these in a systematic and rules-based manner. Its focus on longer-term characteristics, and its rules-based mindset, is one of the key distinctions when compared to traditional active strategies.

The approach is quantitative and based on observable data, including security prices and financial information, rather than on opinion or speculation. As outlined in the book ‘Your Complete Guide to Factor-Based Investing’, industry pioneers Andrew Berkin and Larry Swedroe note that to be worthy of exposure, a factor should meet a number of criteria:

Firstly, it should be Persistent – with the factor working across long periods of time and different economic regimes. Next, it should be Pervasive – the factor should work across countries, regions, sectors, and even asset classes. Alongside this it should be Robust – it should work for different definitions of the factor (for example working for both Price/Equity and Price/Book for the Value factor). It should also be Investable – not just working on paper, but also after considering implementation issues like trading costs. Finally, the factor should be Intuitive – with there being logical risk-based or behavioural-based explanations for its premium and why it should continue to exist.

The origins of factor investing lie in the Capital Asset Pricing model (CAPM) introduced by William Sharpe (1964), with its focus on a single factor (Beta) in explaining investment returns. Over the years, there have been many contributions in the literature expanding upon this. This includes Stephen Ross’s Arbitrage Pricing Theory (1976), which made the case for security returns being best explained by multiple factors. Eugene Fama and Kenneth French (1992) made a seminal contribution with the introduction of their three-factor model, adding the Value and Size factors alongside Beta. This was then expanded upon in by Mark Carhart (1997) to include a fourth factor, Momentum.

Standing today, although the case can be made for a wider range of different factors, academics and practitioners have broadly coalesced around the following set of five widely accepted factors:

Value

Securities with lower prices relative to their fundamental value

Size

Securities with lower market capitalisation

Momentum

Securities that have outperformed in recent time periods

Minimum Volatility

Securities that demonstrate lower volatility

Quality

Securities that demonstrate higher profitability and resilience

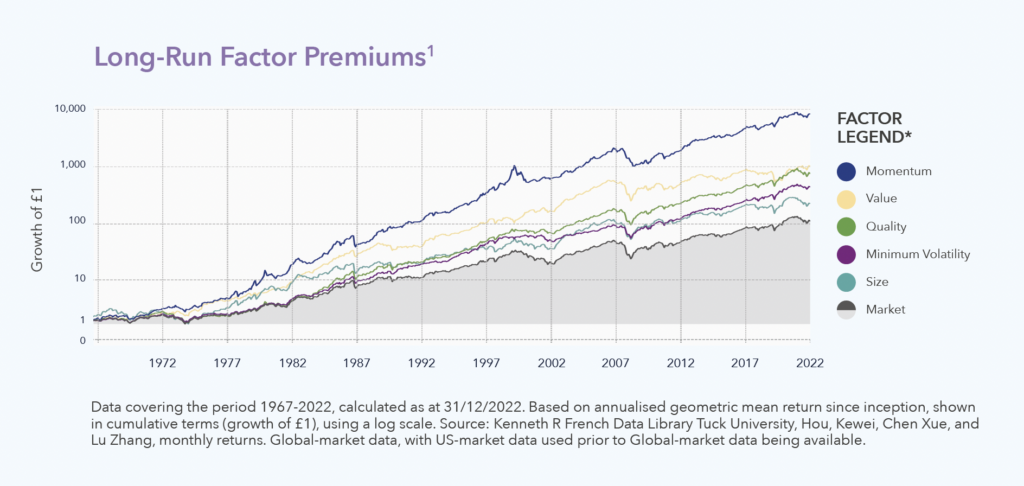

When observed over the long-term, academic research indicates that each of these factors delivers a premium to the wider market, as the following chart, based on equity market data from the Kenneth R French data library and other academic sources, illustrates:

This article series will explore each of these five factors in turn. Rather than beginning with the ‘classic’ factors such as Value and Size, in this first article we’re going to focus our attention on two of the factors of interest in the current economic environment; Quality and Minimum Volatility.

In response to sustained inflation, we have seen the Bank of England and other central banks around the world enact extremely rapid interest rate tightening cycles. With CPI in the UK falling from 6.7% In September to 4.6% in October, the Bank of England’s regime of higher borrowing costs appears to be succeeding, at least in the short term, in bringing down inflation.

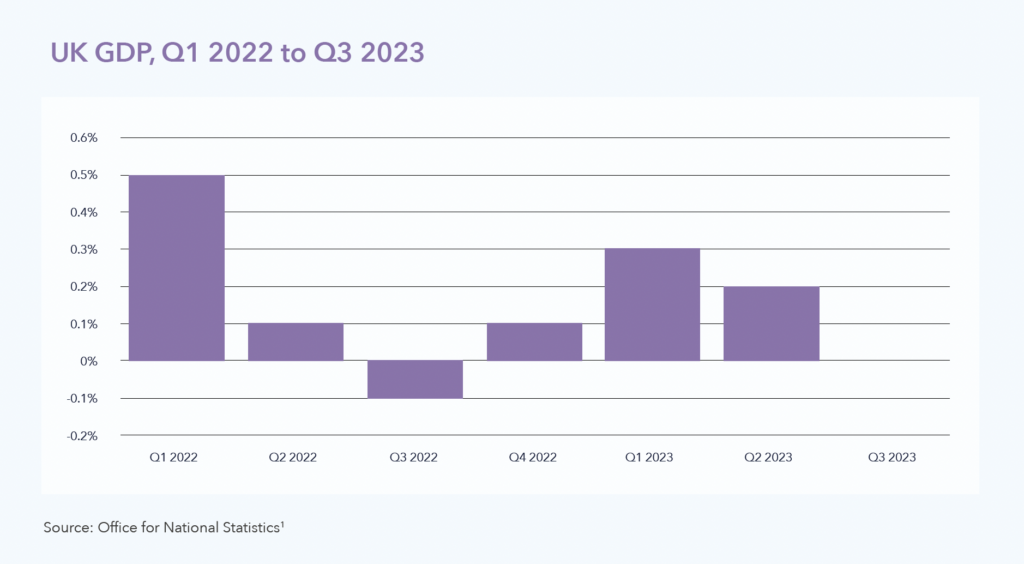

However, this sharp change from the historically low interest rates experienced just a few years ago, is beginning to have a real impact on growth. October saw retail sales volumes in the UK fall to their lower level since February 2021, an almost 3% reduction compared to the prior year. Alongside this we saw UK gross domestic product (GDP) come in flat over the third quarter, compared to a 0.2% expansion in the second quarter.

Despite the Bank of England’s forecasts of flat growth over 2024, an increasing number of analysts are predicting that the UK will tip into recession over the coming months, compounded by the expectation that UK monetary policy will remain tight for some time.

Turning our attention back to factors, we can observe that different factors provide relative outperformance compared to the market at different points in time, and at different points in the economic cycle. While it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to consistently identify economic cycles and resulting factor performance in advance (with timing being one of the most challenging aspects), historically Quality and Minimum Volatility have typically provided stronger returns in recessionary-type environments. We’ll now explore these two factors in turn.

Quality – The Quality factor focuses on profitable companies, with high returns on equity and consistent profitability over time. Through this focus on resilience and profitability the Quality factor can provide a defensive role in a portfolio, a characteristic in favour during recessionary environments – with firms demonstrating high returns on equity and consistent profitability over time being inherently more resilient in an economic slowdown. The Quality factor also emphasises companies with lower leverage, which again leads to increased resilience to a downturn in economic conditions.

There are a number of potential explanations2 behind why the Quality factor can add value compared to the broad market. These include risk-based explanations, which are founded on excess risk-adjusted returns being achievable due to investors undertaking financial risks, and behavioural-based explanations, which are founded on investor psychology and expectations.

Risk-based explanations for the Quality factor include the concept that profitable firms experience various dynamics, that require a risk-premium to be placed on them by investors. For example, profitable firms may attract greater competition due to the potential for greater profits by new market entrants. This increases uncertainty, leading to investors placing a risk-premium on such firms.

Behavioural-based explanations for the Quality factor include the idea that investors may expect that the prices of profitable firms to mean-revert faster than they actually do, which can lead to premature selling. Stated another way, investors might find it psychologically preferable to back the revival of unprofitable firms, than to expect continued strength in profitable firms.

Minimum Volatility – the Minimum Volatility factor focuses on securities with lower volatility compared to their peers. Through this prioritisation of less volatile securities, the Minimum Volatility factor is inherently defensive in nature and can outperform in recessionary environments, compared to the wider market.

However, risk-based explanations for the Minimum Volatility factor break down, as the idea that Minimum Volatility securities have a premium is counterintuitive to conventional investment thinking, which suggests higher rewards are inextricably linked with higher risk.

This leaves us with behavioural-based explanations3 for the factor. For example, we frequently see investors display signs of over-confidence, which can lead to sub-optimal investing, such as the over-paying for attention-grabbing (volatile) securities. Alongside this, we may see such securities generate significant media coverage, leading to increased volatility, and generating demand that leads to further overvaluation. Additionally, we see investor characteristics such as skewness preference, with investors preferring the lottery-like payoffs of high volatility securities, which have the possibility of large returns. This can lead to a premium for higher volatility securities that is not warranted by fundamentals.

In summary, factor investing is an investment approach that involves targeting quantifiable factors that can explain differences in security returns, tilting a portfolio towards or away from these factors in order to generate additional return or reduced risk. Quality and Minimum Volatility are two of the five most widely accepted factors, with their focus on profitable and resilient companies, and lower volatility securities, respectively. These two factors have typically performed well in economic downturns, and they play a core role as part of a diversified factor-based portfolio.

In the next article in the series, we’ll go on to explore other factors in the factor investing toolkit, and how these can add value as part of a diversified factor-based approach.

Blog Post by Jonathan Griffiths, CFA

Investment Product Manager at ebi Portfolios

1 https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/bulletins/gdpfirstquarterlyestimateuk/julytoseptember2023

2 https://www.nbim.no/contentassets/0660d8c611f94980ab0d33930cb2534e/nbim_discussionnotes_3-15.pdf

3 https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/1336482/Foundations_of_Factor_Investing.pdf