“Risk comes from not knowing what you’re doing” – Warren Buffett

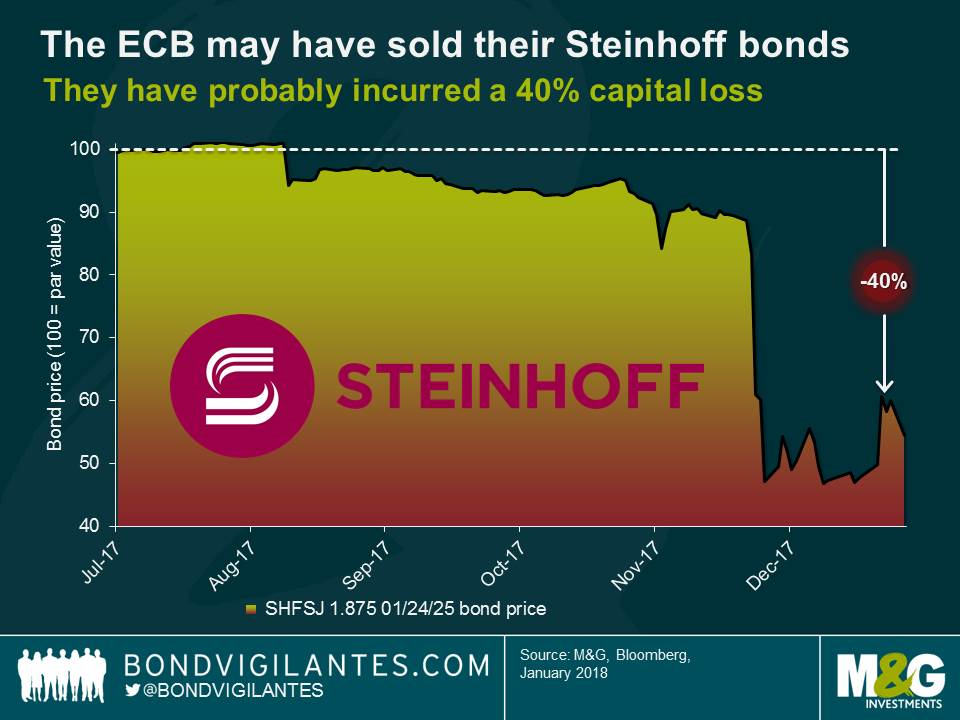

A week ago, a bond mysteriously disappeared from the list of ECB assets being held under the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP). The Steinhoff 1.875% bond due for 2025 had gone – the bond had neither been redeemed nor defaulted, so it would seem that it had been liquidated (i.e. sold).

Lets go back a bit – Steinhoff is an International retail holding company, (owning such trophy assets as Poundland in the UK), originally founded in Germany but it moved its Corporate HQ to South Africa in the 1990’s. The bonds were issued via their Austrian subsidiary (are you keeping up?), in July 2017. It appears that the ECB bought into the issue in that month (possibly directly from the Company). It has a 70% limit on the amount of an issue purchased, so it could only have bought c. €560 million maximum, though it has so far refused to confirm the actual value. The bonds themselves were eligible for purchase because they had (only one) Investment Grade (IG) rating, but news of an accounting scandal, stretching back several years, claimed the jobs of several executives and led to a swift ratings downgrade; (Moody’s dropped the rating by 4 levels to Caa1 – deep into Junk territory), leading to a price collapse in the bonds to the mid 40’s, from an issue price of 100. It appears that the ECB decided to limit their losses (and potential reputational damage) by getting out, incurring a loss which could have been as much as 40% of capital, though as they declined to comment, we will never actually know the true scale of the “inverse profit”, as an ECB bureaucrat might term it.

This has some interesting implications; it has heretofore been assumed that the ECB is a buyer (NEVER a seller) of Corporate bonds [1]. Does this send a signal to the market as to reliability and durability of the ECB’s programme? Secondly, are there any other time bombs waiting to explode? According to UBS, the ECB now owns around €18 billion in notional debt with a junk rating. They loudly proclaim the strength of the Euro-zone economy, but how much could they lose if another recession develops? It appears that the ECB now has little appetite for “fallen angels” (bonds that have fallen into junk status), but how will they account for (and explain) a generalised decline in Corporate bond quality in a recession, which would inevitably lead to more credit implosions? The balance sheet implications for the ECB are enormous and could lead to demands for them to end the policy, (potentially at the worst possible time for issuing firms).

What are the lessons to be learned?

Two spring immediately to mind.

1) Corporate bonds ARE NOT risk free, no matter who the buyer is. In a low interest rate world, many “zombie” companies lurk, sustained only by those same low rates, some seemingly bending the accounting rules to stay afloat. This cannot be spotted (ex-ante) as by definition, no Corporate Executive is going to advertise that fact. Active managers will no doubt point to the importance of credit analysis (“fundamentals” etc.), to reduce the risk of owning such toxic waste, but in realty, except in extremis, there is no reliable way to do so. In addition to owning the bonds, (some €18 billion), several US and European banks have loan exposure to the Chairman’s “investment vehicles”, to the tune of several € billions, all of which are now (as a result of the plunge in the Company’s shares, which were pledged as collateral) further underwater than one of Jacques Cousteau’s submarines [2]. It appears that the Dunning–Kruger effect is alive and well in the Banking industry-a little knowledge is, indeed, dangerous.

2) Diversification works – or at least it fails less often and less completely. Nobody ever went broke by being under-confident which is why EBI bond funds are as diversified as possible. The Vanguard Global Bond Index fund for example, has nearly 9,300 separate issues, whilst the Global Short Term Bond Index fund has 3,144. It may be inevitable that we (indirectly) own the bond, but with that number of securities, the percentage holding will likely be well below 1% of fund assets. As it happens, the Emerging Markets Index fund does have an exposure to the Steinhoff holding company shares (0.24% as of November 2017), which at current portfolio weightings (4.72%) equates to an exposure of 0.011% of total EBI Portfolio 70 assets (4.72 x 0.24%). It is not ideal, but it is bearable. There will be losses, (despite the Central Banks’ efforts to continually levitate markets), so it important to reduce that “event risk” as far as possible. No one has yet devised a viable alternative to diversification, so it is all we have. It seems to have done the trick at least for EBI clients.

[1] According to its’ own rules it is not required to sell bonds that fall to Junk, but a bankruptcy, which leads to the conversion of debt to equity would lead to the ECB directly owning equity, something that is outside of its mandate. It clearly decided not to take on that particular chalice.

[2] JP Morgan, in its results today (Friday) disclosed a $143 million loss as a result of one of these loans (as per Bloomberg).

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.