“And a step backward, after making a wrong turn, is a step in the right direction.” ― Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

It is blithely assumed that the world is in a state of perpetual progress; surveys regularly find that people believe that they are better off than the previous generation, who in turn will be better off than themselves. Politicians sell this hope to get elected (and less frequently re-elected). But is it really so certain? The thought has occurred to me over the last week, as I read what appears to be the annual NHS-related angst, as an Australian export even worse than Fosters lager hits the shores of a Blighty. According to Sky news, one of the few genuinely useful financial innovations of the last 30 years, the ATM, may be about to become less usable, as both demand for cash AND thus their profitability wanes. The rise of terrorism (and the decrepit state of our transport system) has also led to longer journey times on trains, to say nothing of the increasing duration of flights to the US (since the demise of Concorde). The ubiquitous use of antibiotics has led to concern that they will no longer work, leading to the prospect of a revival in the cases of TB, Malaria and so on. Of course, we can still do (or treat) most of these things, but the costs of so doing have risen exponentially over time.

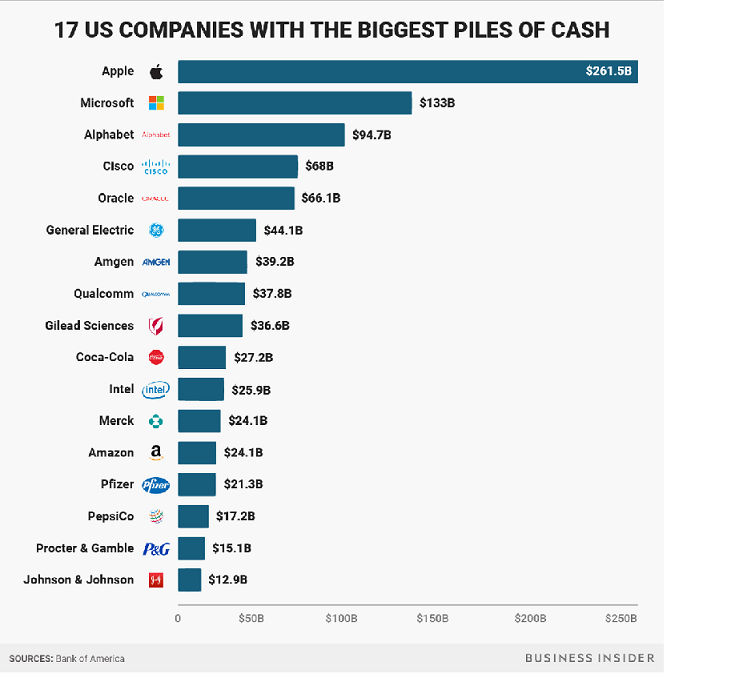

Meanwhile, despite almost endless liquidity injections by the World’s Central Banks, both Companies AND Banks are hoarding cash , leading to inflation targets being missed (but showing up ever more clearly in asset pricing). The dawn of new MIFID regulations may well lead to more accurate re-evaluation of the worth of economic research by those same financial institutions (most likely in the direction of zero).

Thus, regress, (social, economic and otherwise) is a real possibility, if it hasn’t already begun.

What could cause regress?

1) Productivity: over time, if efficiency does not improve, relative costs (i.e. wages) rise, making some services etc, unprofitable. This could be the problem that the NHS is facing.

2) Rent-Seeking: if it pays more to, for example, lobby Government to skew the playing field in favour of existing firms, at the expense of new entrants, there will be less innovation – I am thinking mainly of the Banking industry here; all the regulations imposed on the industry (MIFID) may well have the effect of entrenching the status quo, at the expense of smaller firms, thereby stifling competition and hence new ideas.

3) Luck: some suggest that Betamax was in fact a better video recording system than its ultimate conqueror VHS. If so, a better format lost out (possibly due to superior marketing), with the result that a potentially better solution was abandoned. Is this what is occurring now with Wind turbines? Opinion is sharply divided on its’ ability to sustainably provide the worlds’ energy needs going forward.

4) Mergers/Takeovers: failing firms can be taken over and the assets “sweated” more efficiently (in theory). But in a world of intangible assets (where the sources of profit leave the building at 5pm), this is extremely hard to value. Although not strictly a business example (since profits appear irrelevant to most participants), the world of sport shows many examples of previously successful Football Managers failing due to a lack of ability to cope with “Organisational Capital” structures – the way things are done and organised at a particular business. I doubt whether, for example, Fred Goodwin’s management style would go down well at John Lewis or other partnership-orientated companies.

All of these processes can cause economic declines – if a (sufficiently large) Company (or Industry) gets into trouble the contagion (or Network effect) can lead to problems for the economy as a whole (which is largely what we saw in 2007-09). A demand shock in one sector can have spillover effects, turning a mismatch between Supply and Demand in one area of the economy into a generalised recession in the economy as a whole, as one company’s loss of sales becomes another’s loss of income [1].

Progress (of whatever sort) is thus not certain; societies AND markets do not go in one direction forever (despite what Stockbrokers seem to imply), meaning that “corrections” in both areas are inevitable. They cannot be reliably foreseen in advance, but they WILL happen from time to time – it is how one reacts that determines one’s success or failure in both arenas.

It may be prudent to examine the investor’s goals and risk tolerances; if the investor has achieved (or got close to) their retirement targets why should they take on the risks associated with being fully invested in Equities, especially after such a good run? If their risk profiles do not support the current equity exposure, it may be necessary to look to re-balance back to the target exposure.

In this vein, it is notable that EBI’s model portfolios are getting close to a re-balance, (see here– login will be required). Currently, EBI 70 (UK Bias, which is the reference portfolio) is in reality now EBI 75, as a result of the strong performance of International markets. Conversely, Bonds have fallen (both in relative and more recently in absolute terms), which means that EBI 70 is underweight bonds. The trigger for such a re-balance would typically be a 20% downside dispersion (i.e. an asset grouping is 20% or more below its target weighting), or 25% on the up-side (25% above its target). We are not there yet, as Bonds are “only”16.5% below target. But in the current environment, this may not take too long to be breached, which will automatically trigger a sell equity, buy bonds response. It is not a “free lunch”, but it serves to reduce risk exposures in a disciplined fashion, thereby ensuring that whatever markets throw at us, negative market movements will not de-rail clients’ goals, potentially leading to impulsive decisions, which almost always works against long term interests. The value of being able to sleep at night is often underestimated!

[1] This is all part and parcel of Schumpeter’s Creative Destruction, whereby capital is allocated to its’ most efficient use, but this does require some destruction; Central Bankers, however, have different ideas and seem unwilling to allow any of the latter at all.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.