“If you can look into the seeds of time, and say which grain will grow and which will not, speak then unto me. ” –William Shakespeare.

Suppose you knew of events in advance of their occurrence. You could make money on this knowledge. Seems obviously true, but it isn’t; even perfect foresight doesn’t necessarily ensure a profitable investment- in many cases one would have lost money.

There are three areas in which one might imagine that “insider knowledge” would help an investor, namely, politics, economics and valuations (i.e. company earnings). But in all three, the pitfalls are enormous. Let us look at some examples of how investors could have come un-stuck using event prediction to boost portfolio performance. Obviously, not all outcomes go quite so badly as these ones, but enough do to negate the point of doing it. It seems that markets allow enough predictions to go right to encourage investors to keep trying them. But sooner or later, it will go horribly wrong and when they do, most, if not all of the previous gains are lost.

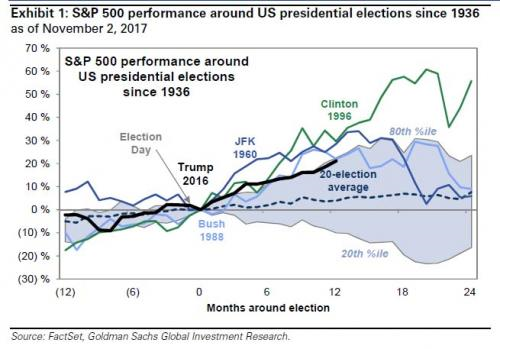

10 years prior to his election, Bill Clinton was still Governor of Arkansas. As the chart shows, Bill Clinton was enormously beneficial to investors…but one would have needed to know the unknowable in advance. Barrack Obama presided over 16.4% annualised returns for US equities (helped by coming to Office during the 2007-09 financial crisis), but again no-one saw him coming. 10 years prior to becoming President, he had just been re-elected to the Illinois State Senate, which is only a few rungs above our Local Parish Councils!

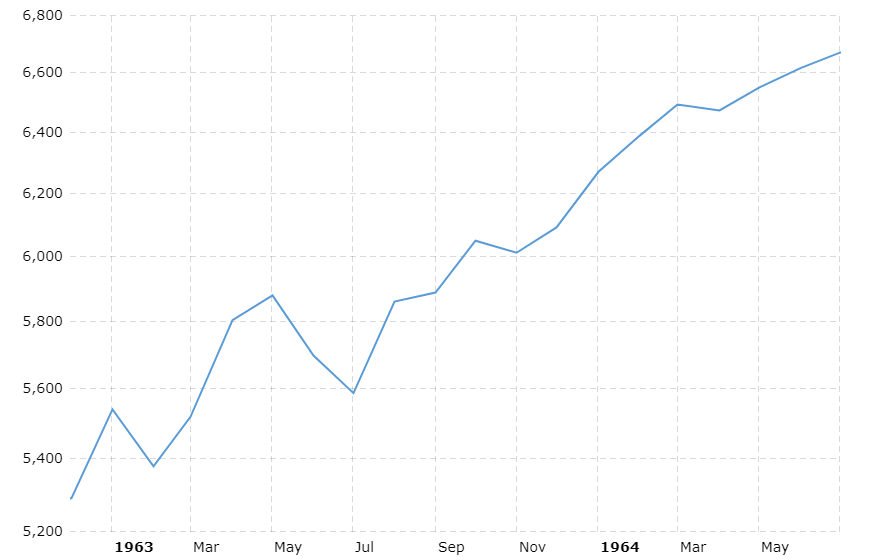

Going further back, the second chart shows the Dow Jones Index over 100 years. See if you can spot Kennedy’s assassination (no Googling the date!) [1]. An event of such huge significance would be an obvious sell signal…except that it wasn’t. Not only does it not register on the Long Term chart, it is invisible on the shorter term one too.

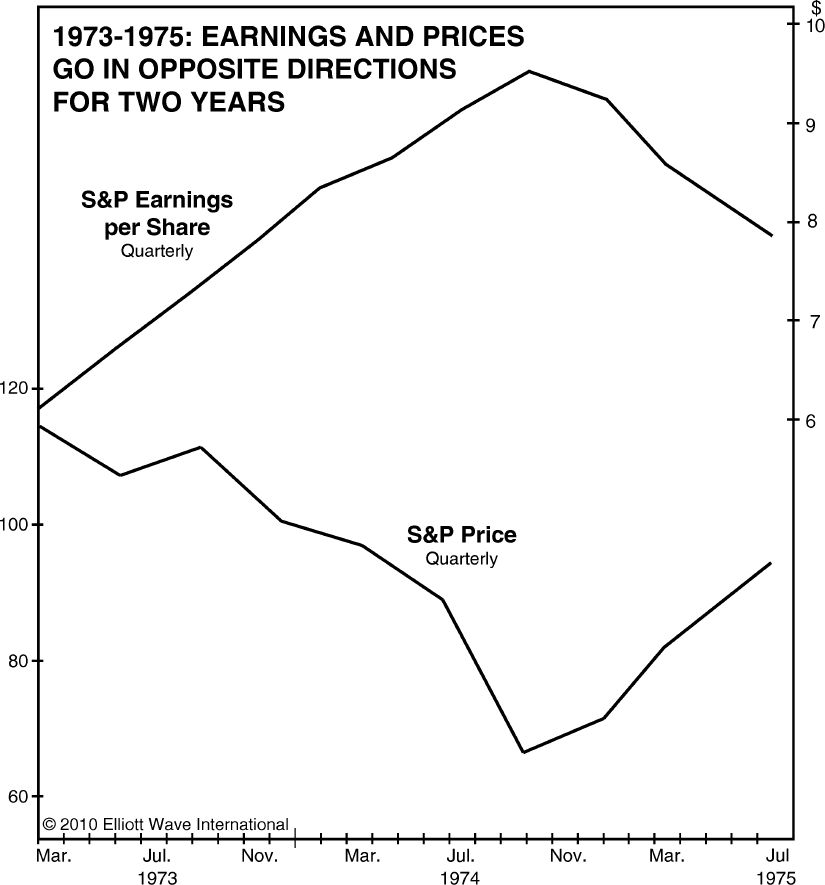

What about earnings? Again, the relationship is not at all clear-cut. During the 1973-74 bear market, Earnings per Share rose for 5 consecutive Quarters, even as the S&P 500 plummeted. The market bottomed just as Earnings were peaking out! Following earnings would have meant enduring a near 50% decline and then selling out at the lows. (The 1987 Crash, was equally unprofitable- earning again dropped sharply post 1987, only to rally once again in subsequent years- the market bottomed in October of that year, and never looked back). Of course analysts constantly tout the power of earnings forecasts as a way of predicting share price moves, but paraphrasing Mandy Rice Davis, “they would say that wouldn’t they”. If there is no consistent link between the two, why bother with analysts at all? (We may get the answer to that question post MIFID!)

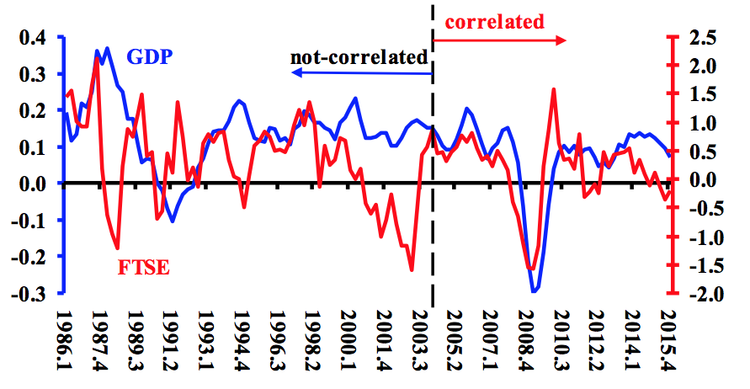

How about economic growth then? Same story. Sometimes the markets and the economy move in the same direction, at other times, not. As economists might say, it depends…but that is of little use to an investor and cannot be relied upon as an investment signal. Often it works, but the correlations are hugely inconsistent, making them all but useless as an investment indicator. Markets tend to anticipate changes ahead of time, whereas economic data is by definition backward-looking. Using it is thus akin to driving whilst only looking in the rear-view mirror. One might as well toss a coin.

Why is knowing the future so relatively useless? Because to correctly “time markets” one needs to know both the news AND the reaction of participants to it. So, even if you get advance notice of an event, you still need to know how others will view it. A feature of bull markets is the ability of investors to “shrug off” bad news, whilst in a bear market, even ostensibly bullish news is ignored. Recent events in North Korea show not even the possibility of nuclear war phasing buyers, whilst (ironically), the “low interest rates are good for stock prices” meme failed to gain any traction at all between 2000-2002 and again between 2007-2009, as prices fell as fast as the Fed cut interest rates.

The persistent failure of Active managers to beat their Benchmarks attests to this problem. It isn’t what you know that matters, it is what you know others know etc, etc. Thus, (for a change) I have sympathy for fund managers, to the extent that they are attempting the impossible, namely to know events and the mindset of others and then to buy or sell before any of them. That they have failed to beat their Index equivalents should therefore not perhaps be a surprise; what is, however, is that investors still give them money to attempt to do so. There is a word to describe this: insanity.

[1] November 22 1963, since you ask.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.