I’m forever blowing bubbles,

Pretty bubbles in the air,

They fly so high, nearly reach the sky,

Then like my dreams, they fade and die.

The always interesting FinalytiQ founder, Abraham Okusanya, (he of Sequence Risk fame, which we looked at here), recently wrote a piece on the futility of trying to spot bubbles, citing the CAPE (Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings Ratio) valuation as the most recent cause of market angst. It does indeed suggest over-valuation, [1] but then it has for a while, thus far without incident; as it happens, the ratio is about to become less expensive imminently, as it is based on the average of 10 years earnings and the (lower) earnings from 2007, 2008 and 2009 will soon drop out of the calculation. It will be interesting to see how the bearish forecasters spin that “news”.

It occurs to me however that the question is mis-stated: IF there is a bubble – and it is an if- a more pertinent question is how did it come about, by whom and what is likely to cause this situation to change? The answer to that question gives us a better indication of whether we need to concern ourselves with the current market outlook.

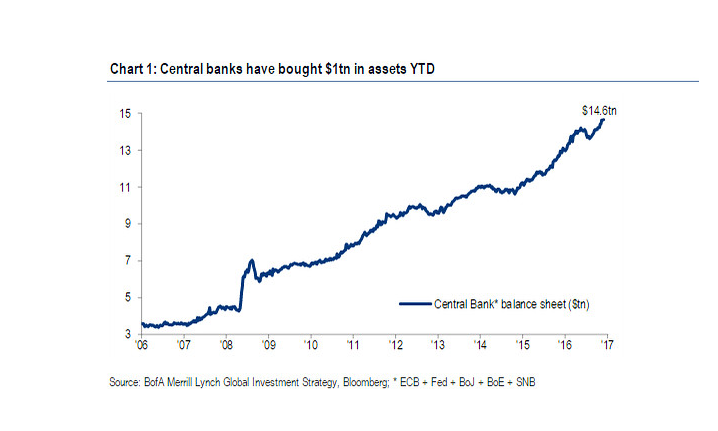

It is said that bubbles are markets awaiting a pin and that pin is the marginal buyer; those investors in any asset class that are willing to pay the highest amount for a given asset (wine, art, real estate and stocks for example), which in turn depends on how much competition there is for that asset. When that marginal buyer stops buying, there is usually trouble ahead and right now it is increasingly looking as if that marginal buyer is the world’s Central Banks, as, since the crisis of 2007-09 they have been increasingly involved in markets in both bonds and equities.

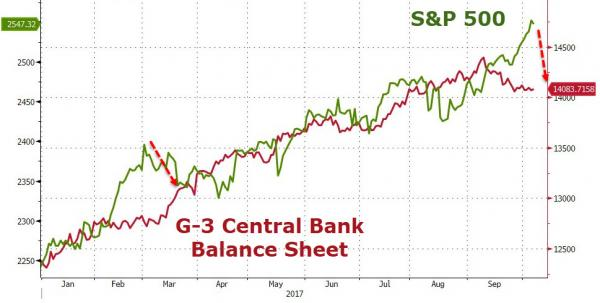

But it is not just Japan, as the chart below shows; (G3= Japan, the US and Europe). The correlation between the moves in the S&P 500 and the size of the G3 Balance sheet (i.e. new money printing) has been, until recently, very high.

Of course, Central Bankers have searched their collective conscience, sifted through the evidence and found no case (for themselves) to answer over the Tech Wreck (2000), the Housing Bubble (2007) or the soaring rate of inequality post-2009, (though some analysts beg to differ). President Trump has sought to appropriate the markets’ gains for himself too, (though he might want to be a bit careful, as prices do occasionally fall, as well as rise!). Still, it is undeniably the case that there is a link between Central Bank money printing (running at $1 trillion this year so far according to Bank of America) and subsequent asset price inflation, even if Janet Yellen confesses to be surprised by the lack of (goods) inflation in the US economy. Maybe she’s looking in the wrong place!

As a result of the relentless growth of CB Balance sheets, alongside $7 trillion in stock re-purchases by US firms since 2003, naysayers are in danger of becoming extinct, with even self-described Bears now almost fully invested in equities, whilst equity volatility collapses to sub 10%, (which implies daily price movements of 0.63%, itself somewhat higher than has been realised over the past 2-3 months), signalling high levels of complacency. Skeptical investors could be tempted to call the peak of the market… but they would have been wrong. It has continued and if anything the pace of the rise is quickening, even if nobody quite understands why.

This scenario can be explained by Preference Falsification, whereby Investors suppress their doubts about an asset’s value because they believe others think it is correct. Hence, SNAP, a profitless Social Media company, offering shareholders zero voting rights went public earlier this year with a market cap of $28 billion. (It has subsequently fallen by over 40% but is still capitalised at over $16.5 billion). Similarly, Netflix last week announced a price rise of $2 for all its users, which saw the share price rocket by nearly 6% [2] and its market cap rise by $4.3 billion, a seemingly gross over-reaction to the news, (though it is up another $5 since then !). Last month Equifax, the credit reference agency admitted a major data breach in which 64,000 UK customers (and over 100 million Americans) had their data stolen between May and July (the delay in the announcement appears to have given several directors the chance to sell their shares in what appears a prima facie case of insider trading). One might have imagined that investors would be wary, especially after a 30%+ drop in the news, but again one would be wrong. The price is up from a low point of $89 to $109 as of Wednesday, emboldening one “journalist” to fearlessly suggest it is a buy as it is “relatively immune from reputation risk” (as it probably has none left!). This readiness to recommend almost anything, on the grounds of its price having fallen, regardless of the reasons for said declines is a sign of investment discipline having gone missing in action, which is almost always a casualty of strong bull trends. All of these examples show that investors are willing to assume that because others are buying them, so should they- a less prosaic way of describing this is “herding”.

Similarly, we have been told that low interest rates justify higher equity prices (they don’t), [3], but the recent rise of US equity markets has coincided with a rise in US Bond yields from 2.04% (as of September 7th) to 2.33% as of this week; at the same time, the Dow (for example), has risen nearly 1,300 points in that time and is nearly 1,700 points above where it was when bond yields were last at these levels (July 7th).

But if investors believe other investors believe this “logic” to be valid, there is no reason for them to sell, which means the “bubble” goes on (and on), cognitive dissonance be damned.

Markets can be both macro-efficient AND micro-inefficient- that is to say, that, overall, prices may be “fair” (since they represent the views of ALL participants), whilst at the same time, some prices can be “out of line” (as they reflect the views of only a small sub-set of the investment population), as the examples cited above attest. There is no doubt that investors have had an easy ride for some time, but this too shall pass.

[1] For a more in-depth analysis of the CAPE, as well as alternative valuation metrics, see this article here.

[2] To see this, note that the Company has 109 million subscribers, which implies that if they all pay the extra $2, it generates $218 million in extra revenue (not profit). If we make the heroic assumption that ALL subscribers pay up, (i.e. zero cancellations) and that the profit margin on this price rise is 100%, they will need to remain with the firm for 20 years to justify the share price move (4.3 billion/218 million = 19.7). Pay TV subscribers are deserting their platforms in droves, which rather contradicts this optimism-they aren’t ALL switching to Netflix…are they?

[3] This market aphorism is an incomplete statement; lower rates justify higher prices ONLY if they remain at these levels for the investment horizon and does not change the reality that returns will be lower going forward as a result of those same higher valuations. Also, consider that if low rates are justified, it is probably due to lower economic growth, which implies no valuation premium at all!

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.