“The growth of the Internet will slow drastically, as the flaw in ‘Metcalfe’s law’ — which states that the number of potential connections in a network is proportional to the square of the number of participants — becomes apparent: most people have nothing to say to each other! By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s” – Paul Krugman 1998

If we were in any doubt as to the value of predictions, the above quote should put it to rest. One wonders how one can be so spectacularly wrong and still retain credibility, but it does not appear to have damaged his reputation – he is a Nobel Prize winner no less!

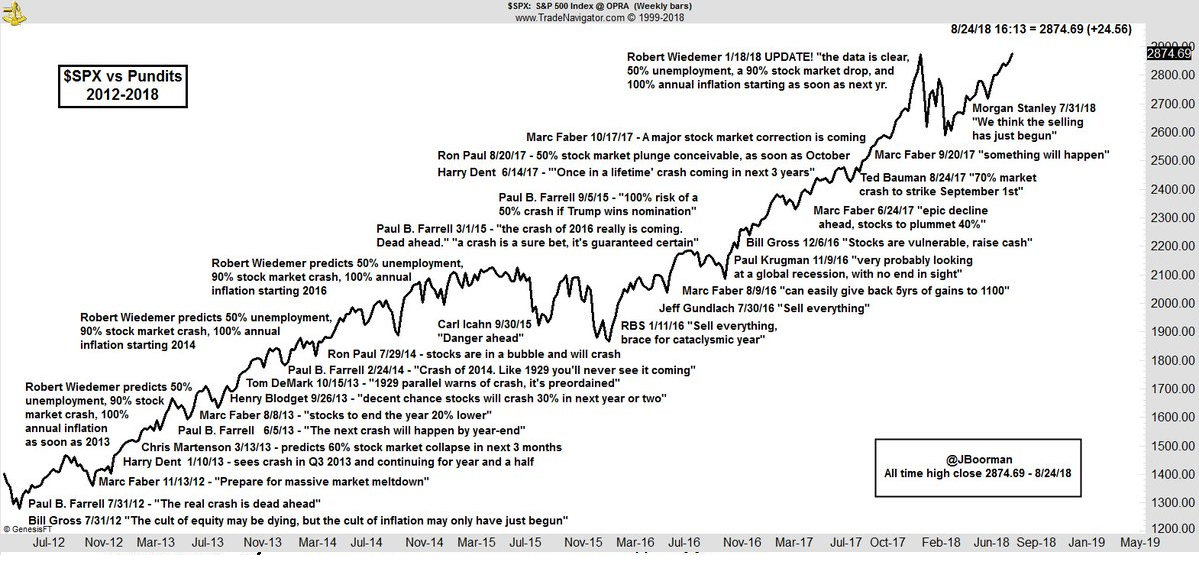

But he is by no means alone in this. The chart below shows how analysts have consistently underestimated the strength of the Global bull market. Most still enjoy an untarnished image in the minds of investors, with all the media time, book deals and so on that comes with “celebrity”.

Krugman’s prediction is somewhat rare, in that it was clearly outside his “circle of competence”. He is an economist, not a technology expert, though he is not above lambasting others for over-estimating their abilities in particular fields. The crescendo of noise regarding the current Brexit negotiations are no different in this respect – we have politicians opining on the economic effects thereof, and economists discussing the politics (from both perspectives), all seemingly unaware of how little they (or anyone else) actually know about the future – as we approach the year-end and an avalanche of 2019 stock market forecasts, this probably should be borne in mind.

Highly capable businessmen too, are prone to this error, not because they are dim, (or ill-intentioned), but because they, like us mortals, are subject to the same mental and emotional biases as the rest of us – they just get heard more often (and in that I am grateful for the obscurity that prevents a more regular public shaming).

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, in his book “Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life” (synopsis here) suggests a reason for both prediction failures and the ability of those making them to carry on, making them seemingly without consequence [1]. They have no “skin in the game” – they suffer none of the (negative) consequences of their disasters, unlike, say, pilots, plumbers or structural engineers. Crashed planes, leaky pipes or collapsing bridges are clear signs of non-performance (and are bad for business and thus one’s career). An economist or market analyst can point to just being “early” in their outlook, (even though in market terms that is a synonym for “wrong”); a political pundit might claim that their faulty election prediction was due to economic issues, which as a non-economist, they could not be expected to foresee. Or a fund manager might aver that a market crash came “out of the blue”, which no one could have seen coming, (except that, usually, someone has). If all else fails, you could always argue that your prediction was “close” – had it not been for that one little thing…

These “experts” appear to attribute successful predictions to their depth of understanding etc. whilst putting their errors down to chance, primarily, one suspects, to protect their self-esteem. Thus, the need to “spin” their efforts as successful, without having to face up to the facts; some seem to even refuse to believe that they were wrong in the first place!

As the chart above demonstrates, there have been a plethora of doom-laden market forecasts almost since the current bull market began – justifications vary, (profit margin declines, bubbles bursting etc.), but they ALL seem to see economic doom (in the form of share price collapses) just around the corner; the updated chart below shows that they could scarcely have been more wrong, yet the views have persisted (and even strengthened) throughout. Nowhere have they seemed to ask themselves why their analysis was wrong, or what did they fail to see? Furthermore, why has it taken so long for them to up-date their beliefs in the presence of information (i.e. share price gains), which contradicted their analysis? Reality (as per the chart below) could have told them in 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 that they were wrong, but this new information did not appear to be assimilated into their belief systems. The confidence expressed in their forecasts was wildly misplaced, based as it was upon a small sample of data [2] and thus led them to err, but the real killer was the unwillingness to assign significant uncertainty to those views, leading to a failure to update those predictions to correct their views according to newly revealed information (i.e. market prices).

At EBI, we know our limits (and there are many), but we also know that everyone else has them too, which is why we take market prognostications with a large pinch of salt. The subject matter is sufficiently complex to make it impossible to be accurate, except by chance. Many investors who took the recommendations above on board have paid a substantial opportunity cost (by not being in markets as they have risen over the last 8 years), a return they can never re-acquire. It is not just hindsight that informs us of this, but the knowledge that evidence is the key to investment success and this must be updated constantly to ensure that our prior beliefs, when challenged, are not retained regardless of the (new) facts. We are thus agnostic on most things investment-related; as Keynes might have said, (though there is no actual record of him doing so), “when the facts change, I change my mind – what do you do sir?”.

As the charts show, doing otherwise can get very expensive…

[1] This could equally apply to policy analysts who argue for military intervention(s) from the comfort of plush offices, without having to face the harsh realities of war, such as injuries etc. and do not know personally any of the combatants. As of 2006, only 1% of US Senators and Congress politicians had children serving in the military. Would the invasion of Iraq/Afghanistan etc. have occurred if that number was higher…?

[2] The argument about “elevated” profit margins, (which would inevitably mean-revert) is instructive in this regard; there is only a very small sample size of examples of profit margins mean-reverting since the late 1990s. In the period to the mid-2010s, the margin expansion was NOT generalised, but skewed heavily towards Technology companies, whilst many other industries saw little or no expansion at all. Even within Industries, there was a “winner takes all” effect, as we discussed in a blog post in August of this year; it was a sign of the formation of quasi-monopolies rather than an imminent warning of margin collapse and there was no substantive basis for the view that this was going to change at that point (or indeed now).

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.