“Invest in emerging market debt for value and diversification, not for “safety,” betting against the U.S. dollar, or an inflation hedge” – Tina Vandersteel, Grantham, May, Van Otterloo & Company (US Hedge fund).

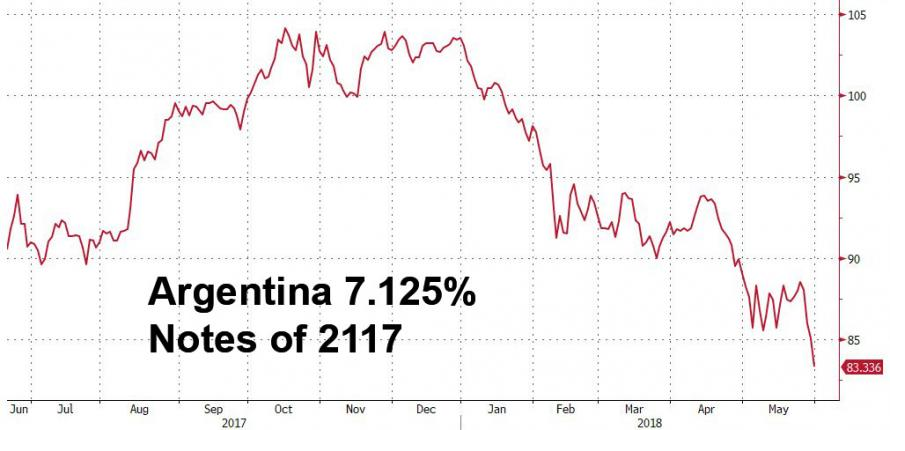

In what appears to be a case of reverse Darwinism, “investors” [1] last year bought $2.75 billion in 100 year bonds of a serial defaulter (Argentina) at a yield of around 7.9% in June 2017, just over one year from emerging from its most recent bout of financial delinquency (which statisticians assure me is number 15 – for both domestic and external debt). Fast forward one year and we are back in the same situation, whereby their country is once again looking for an IMF bailout to avoid a “crisis”. The chart below does not make for happy viewing: even though the bonds were issued at 90, losses have “emerged” extremely quickly.

But the contagion is spreading. Turkey, India and Indonesia are all seeing their currencies fall as investors start to fear that current account deficits, already under pressure from slow growth and high debts, will lead to devaluation (or worse – in this case, defaults). There is talk of Capital Controls, made worse by the fact that the Central Bank of Turkey has denied considering them, (which is sure sign they ARE being considered). The IMF and the World Bank have compiled a list of those most vulnerable, with the usual suspects at the top.

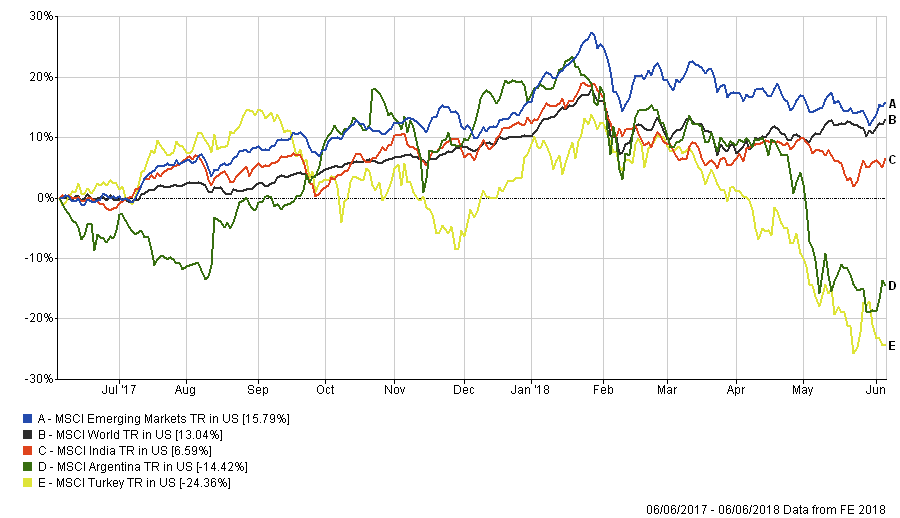

History never repeats exactly, however; this time the EM Equity world has not (yet) generally fallen, as the chart below demonstrates; the problems are concentrated in bond land, specifically in Local Currency Debt. (The charts below reflect Local Currency returns converted to US Dollars).

One would imagine that equities would do better in this scenario as they have some form of devaluation protection built in (via pricing power); according to this article, two-thirds of ALL global growth since 2000 that has come from EM and aggregate Earnings per Share (EPS) has risen sharply over that period – it is just that P/E’s have halved in that time, resulting in no real price progression since mid 2008. It still is where such growth that can be found emanates, however.

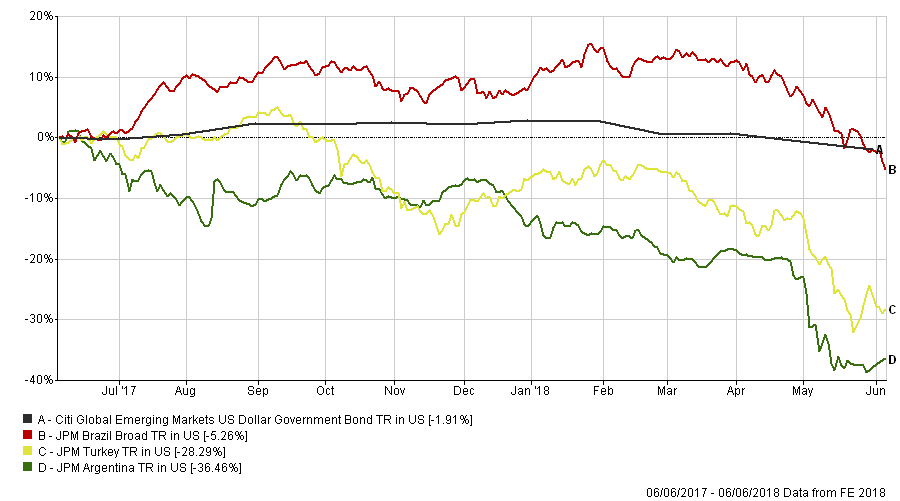

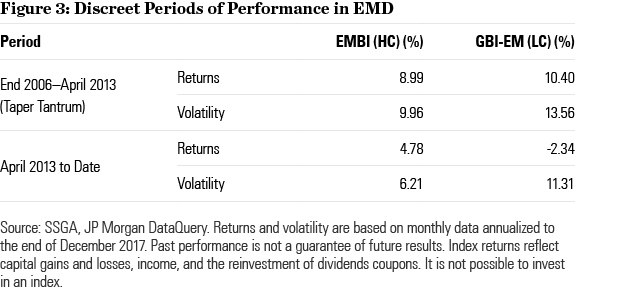

But bond investors have no such support and EM Bond returns are (largely) a function of currency moves over time. Investors have a clear choice – Invest in Hard Currency (US Dollar denominated) or local currency bonds and the difference in returns imply different types of risk.

In the former, the investor is taking no currency exposure and rises or falls in the US Dollar are of only marginal concern – the main risk is credit risk. For Local Currency debt, the investor must take into account the moves of the Dollar, in addition to the default risk already inherent. Having out-performed up to 2013, local currency bonds have seen the worst of both worlds since the Taper Tantrum of 2013, as seen below.

From the issuers perspective, however, it is different – they would prefer to issue in local currency, but find it hard (or prohibitively expensive) to do so. So they issue debt in US Dollars, which creates a liability that they must extinguish on the bond’s expiry by re-paying US Dollars. In effect, they become synthetically short Dollars, which is why a Dollar rise is so painful for EM Sovereigns and Corporates. A rise in the Dollar increases their debt liabilities…

The rise in the Dollar since the low point in February this year has left both Corporates and Governments in the sector with much larger liabilities than they had expected, particularly in the “Sovereign Junk” category, who are precisely those who are least able to bear the load. No wonder then that Central Bank heads in Asia have started to urge the Fed to slow down its balance sheet reductions – by shrinking the stock of assets held at the same time as the US government is issuing more debt, the risk is of Dollar funding being shut off in the region, (which has been falling anyway, but has been falling further in recent months); hence, both Indonesia and India have raised their interest rates to stave off a potential collapse in their currencies (as did Turkey this week), but which only serves to increase default risk for creditors as higher rates increase financial stress.

Since 2015, the amount of EM Sovereign (i.e. government) debt has risen from £43 trillion to nearly $50 trillion as of the end of 2017 – and this is just Local Currency debt (which is arguably easier to deal with as they can just devalue their way out of the problem). This makes the $20 trillion US total debt load look trivial in comparison. These bonds were sold on a yield basis (pension funds were desperate to get a better return than was available in western markets), but things could look a bit different if they don’t get repaid on maturity…

EBI Portfolios’ exposure to EM Bonds is mostly via our holdings in Vanguard’s Global Bond and Global Short-Term bond Index funds, which, according to the latest holdings data (from the December 2017 Annual Report, pages 302 – 471 and pages 535 – 93), indicate weightings in the former at around 2.93% of the total portfolio and 2.51% for the latter fund. (This includes the China weighting of 0.58% and 0.96% respectively, which probably would not be affected by the EM problems currently in evidence). Of the countries cited in the charts above, exposures are c.0.11% (India), 0.15% (Brazil), 0.34% (Indonesia), 0.015% (Turkey) and Zero (Argentina) of total assets. The vast majority are in Hard Currency bonds (Dollars), though Malaysia and Mexico holdings split 50:50 between Dollars and Local Currency denominations [2].

Of course, it may not happen – if the Dollar falls back again, financial conditions in EM loosen once again and all is well. But if it continues its rise, the debate over the ability of Emerging Markets to generate investment returns independently of the West will re-surface anew.

[1] It should be noted in passing that none of the 3 major actors (the Argentinian government, the fund managers who bought the bonds nor the IMF officials) involved in this sordid, repetitive drama have any “skin in the game” whatsoever; they ALL are playing with other people’s money.

[2] If one is of a nervous disposition, one might be more concerned by the exposure to Italian bonds in the light of recent developments, which stands at 4.5% and 4.7% in the two portfolios.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.