In the context of financial markets, Repo’s refer not to repossessions but repurchase agreements [1]. This is the process whereby banks who are (temporarily) short of money can borrow from those who have excess cash so that they stay within their legally required reserve requirements. Generally, the interest rates charged are that of the prevailing Fed funds rate, which s currently in a range of 1.75-2%.

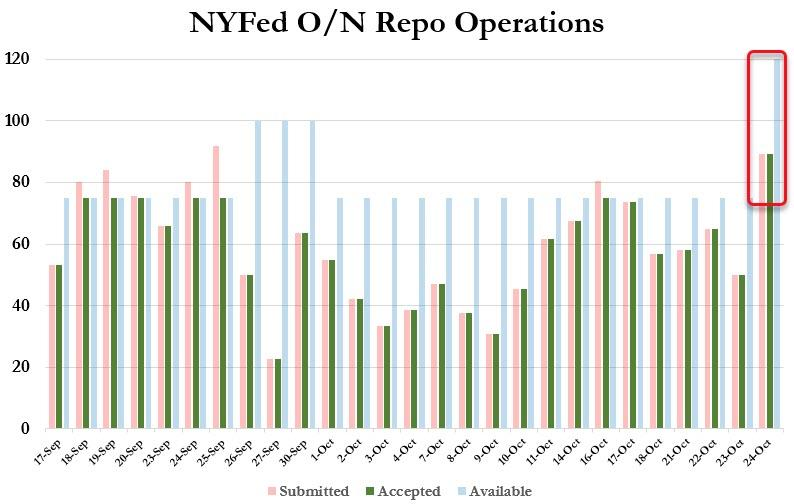

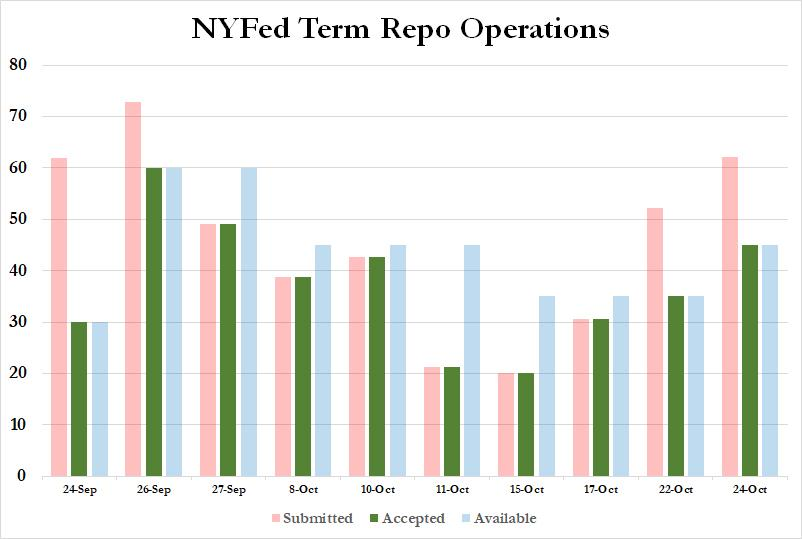

But something strange has happened of late. On the 17th of September, the repo rate rose to 10% (an annualised number), as financial institutions, dealers, etc. scrambled for cash, causing the Federal Reserve to intervene by offering extra cash ($75 billion) to cover the shortfall. They did the same the following day, and market take-up of this liquidity offering rose from $53 billion the previous day to $80 billion. At the time, little attention was paid as it was assumed that the upcoming schedule of Corporate tax payments (at the September quarter-end), was responsible for the shortage of available cash and usually these spikes are reversed relatively quickly. But as the charts below demonstrate, it has, after a small decline, risen back to the levels as of the end of September. This has prompted the Fed to re-start QE, (though they have refused to call it that [2]) and the most recent one was 5.9 times over-subscribed. This latter injection of cash is permanent, as unlike the Repo operations, there is no re-purchase date. Ironically, JP Morgan produced a chart in August, suggesting that increasing issuance of US Treasury bonds, will, by year-end, drain the money markets sufficiently to force the Fed to resume QE-which it has now done. According to a Reuters article, it is that very same bank that may have precipitated the chaos, as it withdrew $158 billion in cash from their Federal Reserve deposits (about a third of the total banking reserves in the system) in the period up to June this year, potentially leaving money markets short of available funding. Some, are questioning the motives of JPM and demanding answers from the US Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin – did they withdraw the money from circulation deliberately, to force the Fed to resume QE?

So, in the space of just 4 weeks, the Fed has gone from “temporary” repurchase agreements to permanent ones, to outright T-bill buying, to announcing that from Thursday 24th, the liquidity provision will rise to $120 billion up to November 14th (which is beyond the month-end AND the putative Brexit leave date). In fact, this is occurring across the globe – the Chinese Central Bank has, over the last week, injected 510 billion Yuan into their financial system, the ECB is doing €20 billion per month QE alongside the Fed. This raises several questions – if the global economy is so strong, as officials say and there is $1.4 trillion in cash deposited with the Fed, why do financial institutions need all this cash? Why are banks not using the interbank market for their funding? Have lenders stopped accepting US Treasuries as collateral and if so, why? At $120 billion per day cash injections, does the Fed (and the banks themselves) know something about the strength of the financial system that the rest of us do not? (On that point, the consultancy firm McKinsey released a report this week suggesting that more than half of all global banks are not strong enough to survive an economic slowdown).

For now, investors appear to be sanguine, but this may change; neither bond nor equity markets have reacted – the S&P 500 is at the same level (around 3010) as it was on September 24th, presumably on the view that more QE will beget more gains in both.

So it remains vital to keep as much out of harm’s way as possible, by investing only in the most high quality, liquid assets available. As equity Indices tend to have the most tradable assets contained within them, they represent a lower liquidity risk than do non-Index constituents. The same is true for bonds- EBI’s bonds have an average credit quality of A; in contrast, as of the end of 2018, BBB bonds (the lowest Investment Grade rating, hence the most vulnerable to liquidity issues), represent 55% of the US I.G. market, compared to 37% in 2007 (according to S&P Global); globally, BBB rated bonds constitute around 17.5% of the total bond issuance outstanding. A recession could lead to credit downgrades (to below Investment Grade) which would force many bond funds to sell (as they are not allowed to own sub-Investment grade bonds as per their investment mandates). The question then becomes, to whom do they sell? At this point, the “liquidity illusion” becomes real -markets seem liquid, but that ability to trade with limited costs evaporates just when participants need it most.

Will investors be able to respond quickly enough to avoid trouble? It is highly unlikely and thus (unnecessary) losses will be incurred, as everyone tries to flee the burning building at the same time. At that point, market participants will be re-acquainted with the trade-off between risk and reward. Index investing is never going to be exciting and low duration bonds will not quicken the pulse either. But that is not what investing is supposed to be about- we have casinos and racetracks for that….

[1] Re-purchase agreements involved the borrowing bank providing collateral (usually US Treasury bonds) in exchange for cash, which they then re-purchase at a specific time in the future (for a small premium to reflect the prevailing interest rate). It can be overnight, or for a specific term (one week for example) but not normally longer than a month. This enables the borrowing bank to remain within its regulatory reserves limits and gives the lending bank a (small) but risk-free return. It is not just banks that use this facility, however Brokers, Hedge funds and some Institutions can also access the money and as such it is a critical component of financial market “plumbing”; should the system fail to work, financial markets liquidity dries up relatively quickly, as we witnessed in 2007-09.

[2] The Fed won’t countenance the T-Bill buying being called QE, but it IS printing money (electronically) to buy assets from financial institutions in exactly the same way as before. Jerome Powell is clearly concerned about the economic weakness implications of calling bill buying QE, but if it looks, walks and talks like a duck, it is probably a duck…

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.