When you see that in order to produce, you need to obtain permission from men who produce nothing—when you see that money is flowing to those who deal, not in goods, but in favours—when you see that men get richer by graft and by pull than by work, and your laws don’t protect you against them, but protect them against you—when you see corruption being rewarded and honesty becoming a self-sacrifice—you may know that your society is doomed. – Ayn Rand; Atlas Shrugged, 1957

The title of this post is a reference to a book published in 2001 that reflects on the experiences of 6 writers of the 20th Century, who became adherents of and ultimately disillusioned with, Communism. It is ironic that much the same can now be said of Capitalism; at the very least it appears to be having a mid-life crisis.

At its heart, Capitalism is a system in which individual rights (including the right to own assets), are recognised and protected by the state, whose only role is to act as a facilitator, ensuring free markets and protection under the law, from both fraud and violence. All are free to cooperate (or not) by means of an agreement to mutual benefit. As Adam Smith posited in the Wealth of Nations, individuals pursuing their own self-interest have demonstrated a remarkable ability to benefit both themselves AND society by so doing.

But in recent years, this appears to have changed (or morphed) into something rather different. This change has been gradual but has accelerated in the last 10 years since the Mortgage Crisis of 2007-09. Central Bank intervention in asset markets, the enormous expansion of QE (Quantitative Easing) programmes and the consequent “financialisation” of the economy has led to surging inequality, as the already rich see their incomes soar, whilst the majority see theirs stagnate. A vast array of new regulations (in financial services, pharmaceuticals or power supply for example), have created new forms of monopolies, (as the bigger, existing players can afford the costs of compliance with the new rules, whilst newer players cannot and thus are unable to compete, thus foregoing market share). Big companies now spend almost as much time-and-money lobbying the government as they do creating products, to the detriment of consumers.

Investors may not have noticed, but voters have. Anti-Establishment parties won big in Italy last month, the AFD entered the German parliament as the third largest party in Germany, to say nothing of the Brexit result and the rise of Donald Trump. In the UK, over three-quarters of the population now favour re-nationalising Utilities and the Railways, in agreement with the stated policies of Jeremy Corbyn. The term “crony-capitalism” has entered the lexicon, to describe the extremely “close” relationship between the business and the political elites, with entrepreneurs and innovators being stifled by the “rent-seeking” behaviour of state-backed cartels.

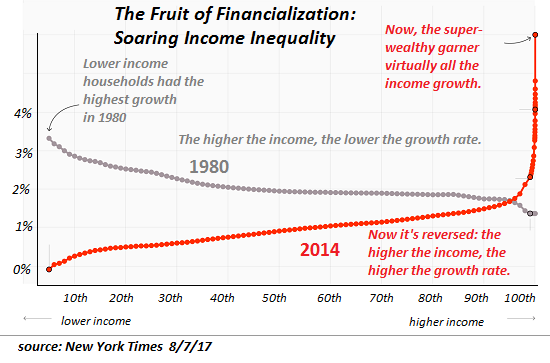

As the chart below shows, the 1% of the wealth distribution have seen massive income growth, whilst the majority have seen little (or no) growth in income at all. This is unsurprising as the former group get the new money first, before prices rise in response.

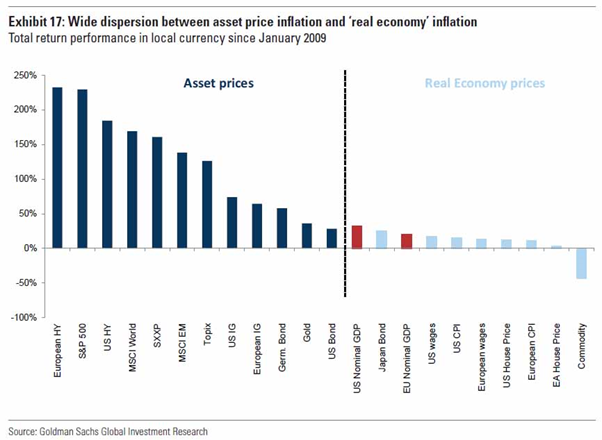

Central bankers say their policies are designed to generate inflation – they have succeeded, though not in the way that benefits anyone who is not invested in asset markets. Compare and contrast the returns to the S&P 500 and that of wages – no wonder those outside Wall Street and the City of London are unhappy. Financial markets now appear to resemble a wild west casino, with no seeming connection between price changes, news, risks or much of anything else. Last week, for example, the Dow was up 700 points, with the US Dollar, Bonds and Gold unchanged, on the day that new economic data suggested that wage growth continued to be anaemic at best and continued chaos in the US Government. At the same time, the S&P 500 was up 4.5% as Donald Trump announced details of what looks to be the start of a trade war! No wonder, therefore, that non-City types see it as just gambling (which, should it go wrong, they assume will lead to a bailout) [1]. They may be wrong about that, but perception is all.

One can try all one wants to refute the arguments currently presented by Corbyn and his ilk (as this article does rather well), but it appears that people have lost faith in Capitalism’s fairness, which is presumably why Jeremy Corbyn’s odds of being the next UK Prime Minister are continuing to shorten, despite his obvious economic illiteracy. According to the Head of the CBI, the prospects of Labour nationalising large parts of UK industries (Rail, Utilities etc), has led to potential investors “reaching for their coats”. But voters have heard that before (during the Brexit campaign) and do not seem to believe it; the increasing perception is that appeals to maintain business “confidence” are an undercover way of pursuing the interests of the elites and as the majority of the young (who are the most supportive of Labour’s policies) have not experienced the chaos of the 1970s, it seems that we are going to have to repeat it. Capitalism has demonstrably “worked” in raising living standards across the globe, but voters no longer appear to be giving it the credit for that achievement.

There are some sobering implications of this for asset owners; markets seem to be unable to “price in” the effect of new information; the Fed has begun the process of un-winding its bloated balance sheet and the ECB and the Bank of Japan are not far behind in this endeavor, yet asset prices have barely moved in either equities or bonds. The difficulty of “discounting the future” is that there is no liquidity, since Central Banks own it all! Thus, the lack of response to the imminent withdrawal of CBs from the market is seen as an “all-clear” signal, whereas it is merely an artifact of there being no assets to trade, thus making price discovery impossible. On Tuesday, (13/3/18) not a single Japanese 10 year Government bond (JGB) traded according to Bloomberg; what’s the correct market price for JGBs? Nobody knows…

The same situation prevails (to a lesser extent) in the Western markets; efficient price discovery requires deep and liquid markets, which are not evident at present. This means that volatility will likely remain elevated, with investors only being able to react after the event.

Of course, for longer term investors such as ourselves (and our clients) this is not currently a pressing concern; but for those looking to withdraw funds from asset markets, the ride could get more bumpy. The recent upsurge in market volatility (as measured by the VIX Index), may be a foretaste of things to come.

[1] Of course, it is possible that the markets do not believe that Trump will go through with it. As he has painted the stock market gains as his own doing, he is politically “invested” in the fortunes of the Dow, which creates an intellectual paradox. The only likely path to reversing the current course is for the stock market to fall sharply (to induce a change of policy). The so-called Dow vigilantes could achieve this with a drop of 5% or so fairly swiftly. But the very act of buying (as has been the case for the last 2 weeks or so) makes a change in policy less and less likely. So this buying brings closer the event businesses (and markets) say they fear most. (No, I am not sure I understand this either!)

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.