The Coronavirus panic has changed quite a few things in its short life.

We no longer stand within two metres of each other without being forcefully reminded to move apart, we no longer seem to mind washing our hands several times per hour or the restrictions being placed on our everyday lives in the name of “flattening the curve” , whilst governments across the world have awoken from their apparent apathetic attitude towards the economy’s performance.

The latest US and UK stimulus packages, in addition to the usual Central Bank monetary responses, cutting rates, printing more money, provided banking system liquidity infusions, are now leading governments into the realm of fiscal policy or state spending; it is almost as if the Coronavirus has decided that we were to have a UK socialist government irrespective of the last election result.

Both the US and the UK have announced spending packages of enormous scale, with other regions, following suit. The US passed a $2 trillion spending bill, (see here for details of where the money would go), which is the largest expenditure in history and includes $301 billion in direct payments to US households, which by most definitions is the fabled “helicopter money”. Whether this can deal with the sharp drop in incomes following the mass closure of firms is debatable, but it undeniably will be more effective than cutting interest rates in addressing most people’s short-term financial needs. In the UK, £30 billion has been found to ward off the coronavirus and Japan, as of the 25th March is “considering” a £421 billion injection into the economy, equating to 10% of national GDP, which also includes cash pay outs to households.

But all this spending has risks – someone has to buy the newly issued debt to pay for all this expenditure and it is not clear who that will be, aside from the Central Banks of course.

One day, there will inevitably be a rise in interest rates. In the UK, Government debt totals around £2 trillion at present, with projected borrowing of around £160 billion this year alone. Pension funds and Insurance companies would no doubt be happy to buy a large proportion of this debt, but with 10 Year Gilts currently yielding just 0.33%, there is little margin for error at these prices and yields. As we mentioned in a blog last year, a breakeven analysis (dividing the bonds’ yield to maturity by its duration) gives us just a 4.8 basis points (0.05%) buffer before a UK bond market investor would be better of holding cash. The US market equivalent breakeven point is 0.16% – a rise in yields of this amount would wipe out the total return for the year and represents just a bad couple of days price action in bond markets.

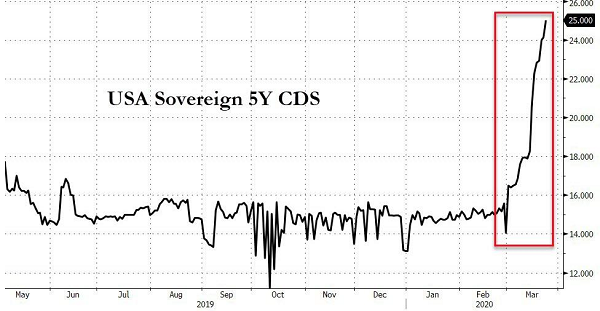

One year ago, we discussed the rise in interest in MMT (here) and, by embarking on huge fiscal expansion, western governments appear to be taking the first steps on this road (backed by Central Banks huge bond purchases). As the next chart shows however, markets have noticed and are now pricing in an increased risk of default – for comparison, though, it is worth noting that UK Credit Default Swaps are at 38, with Japan around 43, so it is only a relative rise in credit risk, rather than an absolute one.

Corporates too, appear to have got nervous – in the past two weeks, there has been a surge in companies drawing down their credit lines with banks. The Fed’s Commercial Paper facility recently introduced should have made this unnecessary, but either due to high Commercial Paper rates (which raises the cost of short-term financing) or a mistrust of the banks, they are clearly acting to forestall a repeat of 2008-09, when banks cut off funding to firms.

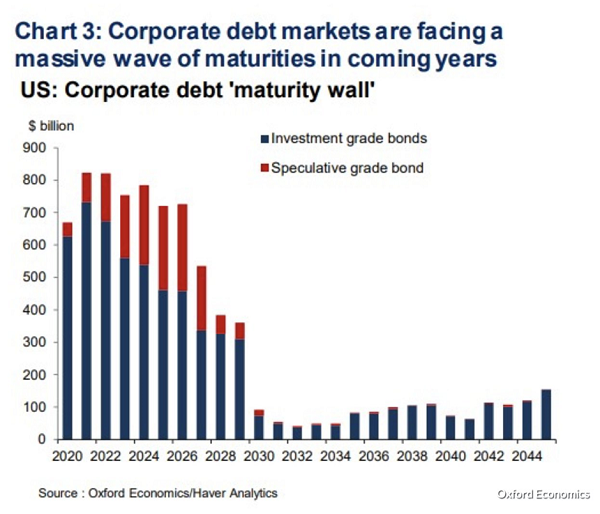

And they do in aggregate need the cash; according to the next chart, there is a wall of debt maturing in the next 3 years amounting to c.$2.2 trillion, (and is bigger still for High Yield and Leverage Loans up to 2024). If firms cannot roll over this debt, they will need to find the money from somewhere to pay the principal back – or default. Credit spreads, or corporate bond yields relative to those of sovereign bonds, will inevitably widen, as investor price in a higher chance of corporate default.

So we may have reached the start of a new era, one where increased government spending is seen as a good thing or at least a necessary evil. But there is always a pay-off and that may well be higher interest rates, despite the interventions of the central banks. There is a slight irony that should all this fiscal stimulus actually work in lifting the rate of economic output, the chances of higher interest rates improve still further, which will inevitably hurt longer dated bonds.

It may be that the famed bond vigilantes will once again exert their power over government spending excesses but this will largely be felt at the longer end of the maturity spectrum. For shorter-dated bonds, the price effects will probably remain more muted, as their interest rate exposure is lower. But a change in how states operate, away from reliance on monetary policies and towards fiscal ones, will likely have profound effects on portfolio construction – many investors have been used to buying long dated sovereign bonds for capital gains, rather than purely yield and diversification purposes.

As recent events have shown, in times of market stress, long dated bonds can fall alongside equities, as panicked investors look to sell to offset losses made on shares. As a result of new government strategies, investors may need to get used to different relationships between long duration asset classes (equities and bonds) than have hitherto been the case, as it looks as if we may be heading into a new realm – one where the state is responsible for an increased share of direct national expenditure. The coronavirus era and the response to it may herald the start of a new paradigm for economics – and markets too.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.