A common saying in finance is that “markets take the stairs up and the elevator down.”

We are often asked by clients to explain the reasons for the dramatic fall from grace of UK equities relative to the rest of the world. Many suppose that it is a function of the fall in Sterling as a result of Brexit (and the political paralysis that has followed). In fact, all other things equal a fall in Sterling would serve to raise UK plc’s earnings due to the translation effect (i.e. a lower value of the pound would mean a higher return on the overseas income, once that money is converted into Sterling) and as domestic revenues for FTSE 100 firms are fairly low (c.22%, meaning 78% of the revenue is generated overseas), [1] a fall in Sterling is seen as good news for UK share prices.

But it is not quite as simple as that in reality; Firms involved in cross border transactions (in whatever form) routinely hedge their currency as well as product exposures. BP, for example, would sell their oil production forward to “lock in” the price they receive for their Oil AND hedge the currency risks associated with buying and selling oil in US Dollars, (most often in proportion to their global asset and liability profile across the globe). If a CEO wanted to be fired (and they are all too fond of the status, prestige and wealth associated with their positions to do so) all they need do is announce at the next AGM that they increased production etc. but lost money on currency effects (a fall in the US Dollar would achieve that for most mining and commodity companies). They would get their wish almost immediately, as it would increase the risk of large earnings fluctuations (which in turn would lower the perceived “quality” of these cash flows [2], and thus negatively affect the share price, leaving shareholders unhappy. Rarely would a CEO countenance such a risky course of action, so currency effects are not likely to be the (direct) cause of the UK equity markets woes.

So we probably have to look elsewhere for an explanation; the most obvious is the behaviour of “big money” investors (Sovereign Wealth fund, Global Pension funds etc) and how they choose to invest. They invest first by currency and only then by asset class, so they will take a view on, say the US Dollar and only then decide what asset in that currency to buy. So, the determining investment factor is currency; Sterling, therefore, would seem to have ranked fairly low on the list, a view that was likely only reinforced by Brexit. The ongoing political chaos since then has no doubt made the pound even less attractive and when one considers the 4-1 odds currently being offered on Jeremy Corbyn potentially becoming the next UK Prime Minister, one can see no immediate “all clear” signal ahead for these institutions. An avowedly Marxist PM is unlikely to attract Global Capital anytime soon.

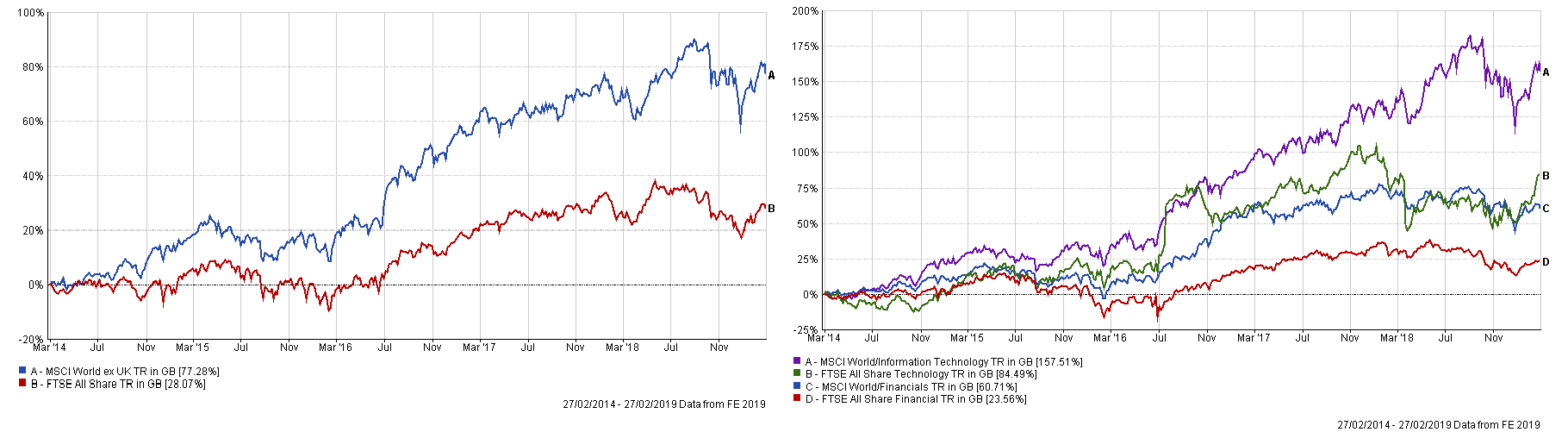

Regardless of why it has happened, (and one can speculate endlessly about the causes), there is no doubt that it has. The charts below show this clearly, dating as they do, pre-Brexit. Although the Energy (Oil mainly) and Mining sectors (in which the All Share is overweighted) did outperform the MSCI World Sector equivalents, this was overwhelmed by the (negative) contribution of Financials (26.26% of the All Share, compared to 16.24% for the MSCI World Index) and most importantly Technology (14.92% in the MSCI Index versus just 1% in the All Share); so, the UK Index lost out as a result of being overweight an underperforming sector (Financials) and heavily underweight a strongly performing sector (Technology). (All the cited weightings are from the factsheets of the All Share and the MSCI World as of 31/1/19).

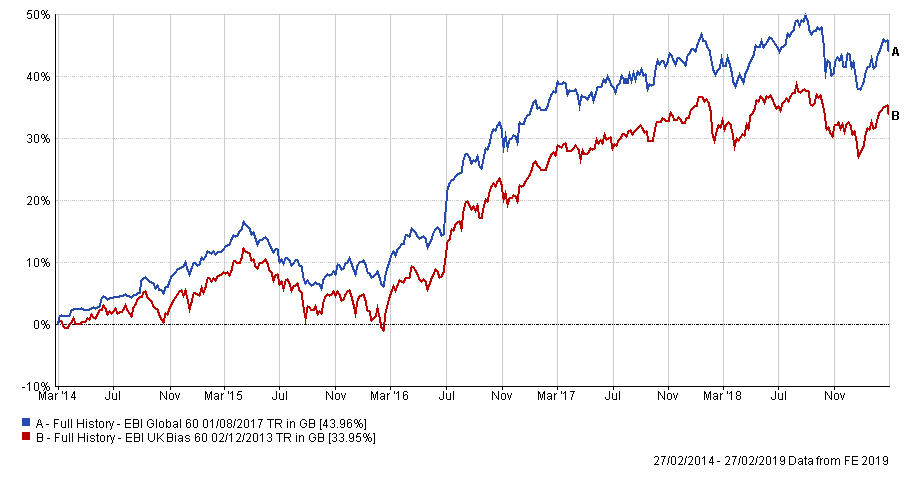

The large multinational firms, tend to see their share prices dominated by international events rather than what goes on in their home country, thus providing a source of country-specific risk diversification not available to their smaller cap brethren. (Smaller firms are more exposed to domestic “shocks” than the big firms, by virtue of the latter’s’ higher non-UK revenue streams). This is part of the rationale for our preference for Global, rather than UK Biased portfolios (and may be at least in part a reason for the much better returns arising from the former rather than the latter), which is currently running at an annualised 1.45% per annum (see below – note once again how the Global portfolio has consistently beaten the UK version from before Brexit).

The rationale for diversification generally is to lower overall portfolio volatility and this applies equally to a country, sector, and currency. There is no reason why the UK could not suddenly awake from its slumber and power ahead of global markets, but is this a likely occurrence and if so when? This we cannot know in advance and placing too many eggs in one investment basket is never a formula for investment success – all it does is to elevate overall portfolio volatility, which in turn makes it harder to cope with the inevitable periods when (UK) asset prices fall. In an age when financial markets are increasingly interconnected, it makes sense to be exposed to all of them, rather than one small, increasingly isolated part of the globe.

[1] In contrast, according to Morningstar, 62% of the revenues for S&P 500 companies are derived from the US; Japan and Australian firms get around 60% of their income from domestic sources, while in Europe, the figures are lower still, with around 20% of Dax (in Germany) constituent’s income coming from their home market and only 17% in France. Going into revenues by company size, US Small Cap shares generate 81% of their sales in the US, 50% of UK firms’ trading is done domestically, whilst in Continental Europe, the figure is between 30 and 40%. The more service-orientated a company is, the more likely it is that they will generate revenue domestically as services, for example, are difficult to put in a box (or a cargo plane).

[2] Quality of earnings in this context refers to their stability (and thus their predictability). Investors generally prefer firms to have smooth earnings flows as they are seen as more reliable.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.