Following on from the famous quote that Helen of Troy’s was the face that “launched a thousand ships”, Isaac Asimov, the science fiction writer claimed to have invented a new measurement unit, the millihelen, which corresponds to the beauty required to launch one ship. The Times newspaper this week pointed out that, as per a letter to the New Scientist as far back as 1959, the inverse also applies; -1 millihelen would be enough to sink one.

There has been much market angst recently over the rise of inflation, as bond prices have fallen, raising yields which in turn has put equities on edge. But would a rise in interest rates actually be the -1 millihelen necessary to sink the economy?

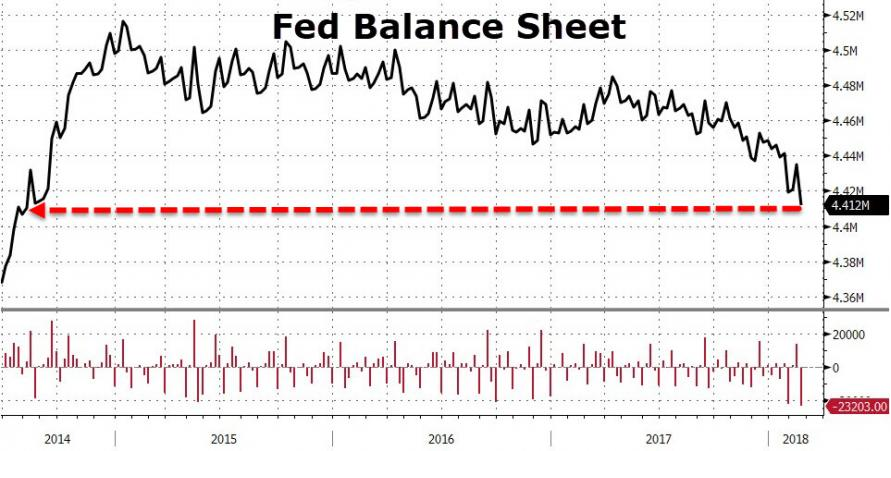

Several reasons are being advanced for this newly found source of concern; global growth is (said to be) picking up, partly as a result of the tax cuts recently passed in the US (which also serves as the justification for selling the Dollar, namely that other countries are likely to be the net beneficiaries). US job growth (and the likely wage pressures resulting therefrom), rising US CPI numbers and better GDP figures will, it is believed lead to inflation, long dormant, to rise phoenix-like from the ashes. Combine this with the huge amount of new bond issuance (and the short-term nature of the current maturity profile) the insistence of the Fed that they will be raising rates at least 3 times this year and bonds look to be a slam dunk sell. Oh, and the Fed’s Balance sheet has begun to shrink (see below), albeit modestly thus far.

Investors appear to have taken note, Bond shorts are at record levels too.

First, we have to look at the theory (sorry- I will resume my normal ramblings momentarily); the best way to understand the relationship between money and inflation is through the Monetary Exchange Equation. Re-arranging the formula (which is an accounting identity, that is, it is by definition true) you get;

P (Inflation) = M (Money Supply) + change in V (Velocity of Money) – Y (Output Growth, a loose synonym for Productivity).

So if M grows 7%, V falls by 3% and Y grows 3%, the resulting Inflation rate is (7-3-3) 1%.

For convenience, analysts often assume one or more of the variables can be held constant when making forecasts, (which explains why so many forecasts of inevitably higher inflation resulting from QE etc have not yet borne fruit). In reality, they are all in a constant state of flux.

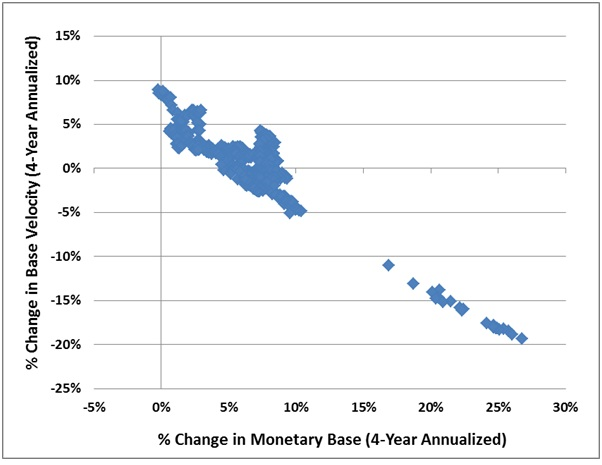

The one measure that Central Banks cannot control directly is the Velocity of money (i.e. how fast it is spent). It is driven by two things – the LEVEL of Interest rates and what is called Liquidity Preference [1]. The chart below illustrates the latter’s relationship with money supply growth – as the money supply grows, the Velocity of Money declines.

There are some problems with the current market analysis however, one of which appears to be facts; if this week’s Chinese and Japanese data is a guide, growth is anything but globally synchronous and it hasn’t got any better for a while. The Federal Reserve appears ready to raise rates, possibly 4 times next year to counter the inflationary “risks”, even though inflation actually remains at 1.7% p.a. , below the 2% target. Thus, the bond market’s reaction (lower prices, higher yields) may end up doing the Fed’s job for them with regard to inflation. Given the still large debt levels across the globe, it is entirely possible that the economy will slow down of its own volition, or that the rate rises being envisaged actually cause the next recession– according to a Deutsche Bank study, 9 out of the last 11 tightening cycles have ended in a recession! Furthermore, every time since the mid- 1980’s that US 10 year rates have risen up to the longer-term trend line, “something” has blown up (see here and here).

It may well be, therefore, that the Bond market is reacting to the prospect of increased supply, reduced QE-backed demand (as noted above), but that inflation is only a small part of the inputs into lower bond prices/higher yields. Certainly, the theory outlined appears to vindicate concerns regarding inflation, but the likely market response to its’ emergence is likely to be self-cancelling, (particularly if the Dollar re-awakens from its 16-month slumber) – investors would likely raise the prospective odds of a recession. Can consumers really withstand higher debt payments? It seems implausible, absent a cascade of defaults.

Here at EBI, we maintain our composure; a bond portfolio consisting of short-dated, low credit risk bonds will shield us from any major losses, as the duration of the assets is below 5 years. A rise in interest rates by another 1% would lead to a decline in our Bond portfolio of c.5% (assuming a parallel shift on the yield curve). For equities, the effect is less clear-cut, but P/E ratios would most likely fall. As of 28/2/18, the MSCI World Index is at 2118, on a P/E on 20 x; a drop to just 19 x would lead to a 5.36% fall (to 2004). The bigger the P/E “de-rating” the further the likely decline would be.

Of course, nobody really knows; bond (and equity) prices reflect a number of inputs, which are constantly shifting and can only truly be discerned ex post. Since we cannot observe these inputs directly, it makes little sense to try to preempt them. As long as risk tolerances are maintained, we can remain relaxed about what comes next. The only certainty is that the majority of forecasts will be wrong – EBI’s included.

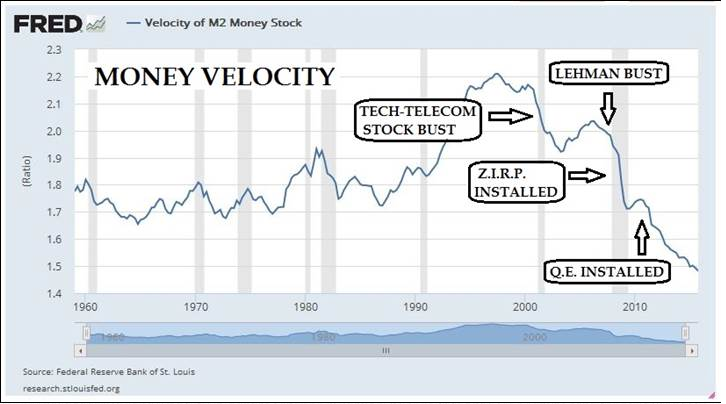

[1] If interest rates are rising, the “opportunity cost” of holding cash is high, as interest (in the bank for example) is foregone. Thus, cash becomes a “hot potato” which people are trying to get rid of (thus raising the velocity of money). In times of low-interest rates (or when there is an economic crisis), the velocity of money falls, as it either represents only a small loss in interest or in fact becomes a desirable asset to hold in and of itself). Incidentally, this helps to explain why successive interest rate cuts by the Fed (and others) in 2000-02 and again in 2007-08 had little effect, as cash itself was what people wanted, almost regardless of the rate of interest it commanded.

So, as one expands the money supply, one is implicitly reducing the velocity of money (almost exactly proportionally) and vice versa on the upside. The chart below illustrates this effect clearly. Note that the Velocity of Money has collapsed, neatly coinciding with the history of Fed rate cuts. (The situation is the same in other countries too).

This is why the QE programmes post-2009 have not seen generalised CPI/RPI inflation breakouts – though asset price inflation is a different matter entirely. (One might have imagined the Ph.D. Economists (ahem, Ben Bernanke) would have known this, which begs the question as to what was their REAL motivation for QE etc).

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.