ZIRP- Another Japanese innovation, this time from the Bank of Japan, whose aim was to stimulate the Japanese economy by having a Zero Interest Rate Policy: so far (15 years and counting), it has had an extremely limited effect.

NIRP- A variation on the above theme, whereby Central Banks (particularly the ECB, but not limited to them ) employ a strategy of Negative Interest Rate policy: the likely economic result will be much the same.

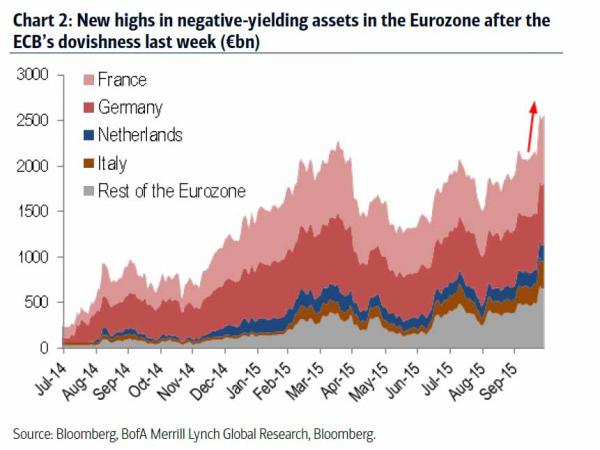

We briefly discussed (here) the phenomenon of low-to-negative Bond yields and the consensus expectation of rate hikes, which occurred at the beginning of 2015. At that point, according to JP Morgan, nearly €1.4 trillion of government debt with one year or more maturity traded below zero yield. Soon after, yields appeared to re-acquaint themselves with sanity, but this week, according to Reuters, the Italian government sold €6 Billion of 6 month bills at a -0.055% yield, having sold 2 year paper at -0.023% the day before. The ECB has made it clear that they could unleash new stimulus to push inflation higher in the months to come, and no-one in the bond market appears to doubt them; as the next chart shows, German 2 year yields are now a fair way below official rates. The Swedish Riksbank responded in kind, by expanding their QE for the 4th time in 2015, and it is widely believed that the Swiss National Bank will not stand idly by and allow further Franc appreciation. So the monetary parcel is passed on once again…

The amount of negative yielding Euro zone debt now stands at a record €2.6 trillion, (see chart below) as disinflation takes hold in most Euro countries. The irony is that the policies espoused by the Central Banks as the solution to deflation is making cash more valuable, (especially if you have to pay to hold cash in a Bank), thereby contributing to the very trends they are trying to arrest. As James Montier points out, “There seems to be a perception that central bankers are gods (or at the very least minor deities in some twisted economic pantheon). Coupled with this deification of central bankers is a faith that interest rates are a panacea. Whatever the problem, interest rates can solve it. Inflation too high, simply raise interest rates. Economy too weak, then lower interest rates. A bubble bursts, then slash interest rates, etc., etc. ” . This faith is about to be tested.

The era of negative interest mortgages has now arrived in Denmark, and may be coming soon to another European bank near you (sadly, probably not in the UK, though). Negative interest rates, however, are much more likely as Banks may be inclined to pass on the costs of NIRP to customers. When they do occur, there is likely to be a much higher demand for cash, (and equities ?), as depositors flee banks altogether. [This would have deeper implications, but we will get to that in a later post].

The much bigger questions revolve around why this seemingly counter-intuitive policy has been adopted so widely, especially as it is so clearly failing to achieve the desired aim of stimulating economic growth. [Of course, it has been wildly successful in stimulating asset markets, but fewer and fewer people now believe in the “wealth effect”(1) and it is not helping the real economy]. One possibility is the following:

-The term “Group think” was coined by Irving Janis in 1972 (2) to explain the cause of the Vietnam War and the Bay of Pigs debacle(1961). He isolated 9 symptoms of this phenomena:

■ A tendency to examine too few alternatives;

■ A lack of critical assessment of each other’s ideas;

■ A high degree of selectivity in information gathering;

■ A lack of contingency plans;

■ Poor decisions are often rationalised;

■ The group has an illusion of invulnerability and shared morality;

■ True feelings and beliefs are suppressed;

■ An illusion of unanimity is maintained;

■ Mind guards (essentially information sentinels) may be appointed to protect the group from negative information.

Tellingly, he also states that “A group is especially vulnerable to group think when its members are similar in background, when the group is insulated from outside opinions, and when there are no clear rules for decision making”. This seems remarkably like a Central Bank committee make-up (think BOE/FED etc), and could be said to be characteristic of the media too, (on such diverse topics as Climate Change, and Jeremy Corbyn’s electability). Can this explain the adoption (and maintenance) of what appears to have been a failed strategy ?

-Another possible rationale comes from Behavioural Finance theory:

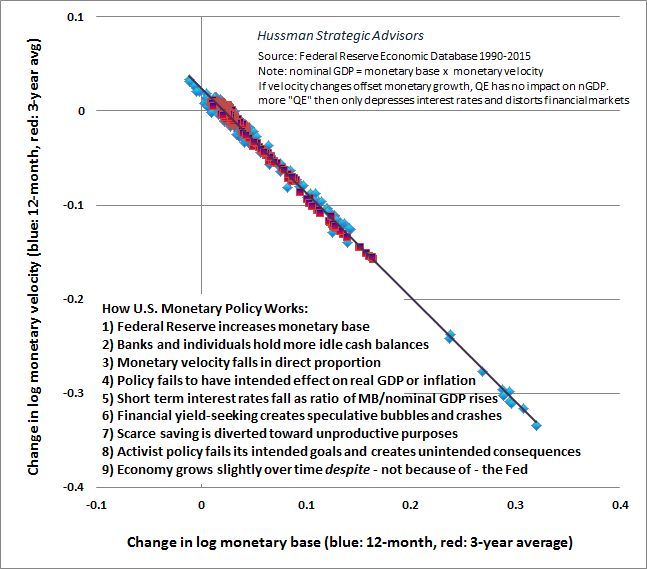

Central Banker-bashing aside, it is a near universal trait to try to reduce complex problems to simple solutions, or heuristics (3), to take mental “short-cuts” to arrive at answers, often using associations, rather than evidence. The Human brain can only work in two modes-System 1, which is fast, associative and intuitive, working with whatever information is available, and System 2 which is more orderly, process and analysis-driven. The latter requires effort and time, but humans are lazy and often default to the former. System 1 (as Kahneman calls it), is “radically insensitive to both the quality and the quantity of information that gives rise to impressions and intuition… It is the consistency of the information that matters for a good story, not its completeness.” System 1 is a machine for jumping to conclusions. The stylised chart below highlights the problems Central Banks are currently wrestling with- it is not necessarily the fact that the “intervention ” in markets doesn’t work as originally intended that is the issue here. It is the apparent expectation of achieving a different result with the same policy (a sort of Einsteinian madness). (4) Truly effective policy must relieve some binding constraint on the economy; it is not clear that still lower interest rates will suddenly change things – if the Swiss economy can’t grow at negative rates, it will most certainly not grow faster with even lower rates/yields etc. Central Banks appear to be engaging in “System 1” thinking, assuming that if their policies don’t work the first time, all it needs is much more of the same to achieve their desired results.

Below gives an indication of the timeline of the Fed action and Market reaction function thus far.

Authorities have resorted to asset purchases to try to revive “animal spirits”. Stocks/Bonds etc have risen way ahead of the “real” economy in growth terms, but as this post makes clear, this is a dead end. As soon as the Central Bank buying stops, the market(s) drop (as we saw in late August, as the market began to price in a September rate hike ). The market is now anticipating a December hike by the Fed- as we get closer to that date, market stress will likely increase. What will the Fed (and others) do if there is a proper market crash -10-20% in one day? The last Fed statement (here) cited “Global events” (i.e market falls) as a reason for standing pat. Can they say this again without ruining their credibility? If not, the next step could be QE4 or even “Helicopter Money”(5) as advocated by Economists and feared by some Analysts. Then we would be venturing into radically new territory…

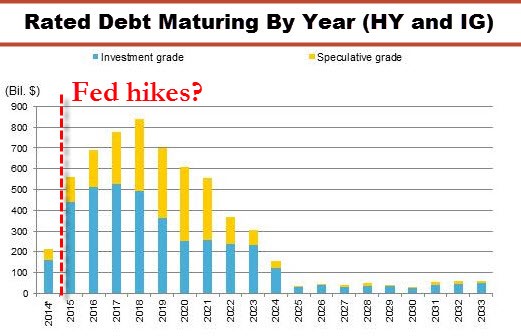

Finally, the chart below illustrates the dilemma (in this case for the Fed, but it applies in Europe too). Anything more than a token rate rise will cause major pain for those companies that have issued bonds (in some cases to fund stock buy-backs) which they will have to redeem on maturity. In an environment of low-to zero economic growth, the repayment of Bond principal will become progressively more difficult. This is the main reason why the “doomsday scenario” for bonds is still unlikely to occur, and why we pay little attention to those forecasting the demise of the bond market. That said, negative interest rates do not portend big future returns; EBI portfolios are tilted towards the shorter-dated end of the bond market not due to any particular market view, but to dampen overall Portfolio volatility. Either way, we are confident that we will continue to harvest decent asset returns regardless of how “interesting” things get in the run up to the next Fed meeting on December 16th.

[Up-Date: as of 2 pm. Friday, the US Jobs report has led to a large US Dollar jump as the Non-Farm Payroll data seemed to strongly support the idea of a rate rise. The odds-compiled from the Fed funds futures contract- of a rate hike have gone from 38% pre the report to 74% now. The market is now forecasting another rise in March (37% likelihood versus 25% this morning). Of course, there is still 6 weeks before the decision must be made, but for now the onus is on the Fed to explain why they will NOT be raising rates].

- (1) The theory that profits generated in the stock/bond/property markets will be spent in the real economy.

- (2) Janis ( 1918-1990) was a Research Psychologist at Yale University,and Emeritus Professor at the University of California.

- (3) Daniel Kahneman (” Thinking Fast and Slow” October 2011, Farrar Strauss and Giroux).

- (4) Although Einstein probably didn’t say it, the quote still stands.

- (5) The theory here is that the Government simply credits Individual’s Bank accounts with cash, issuing Bonds to finance this expenditure, which the Central Banks then buy. This would by-pass the Banking system altogether, and would be more likely to be spent (or if saved, would make them more credit-worthy, allowing Private sector banks to lend to them again).

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.