EBI Portfolios adopt a buy and hold strategy, which means that one year performance is not a sound basis for decision-making with regard to asset allocation etc. However, we recognise that clients wish to know how their assets are performing and so a yearly review is undertaken to allow them to understand the sources of returns; it is not always possible to discern the rationale for why millions of investors (most of whom are much better informed than we are) do what they do, so any interpretations offered here are just that-interpretations- and may be in error. But taken as a rough guide, it may help investors to better understand how markets have performed in 2019. On the basis that any information is better than none at all, we offer the below.

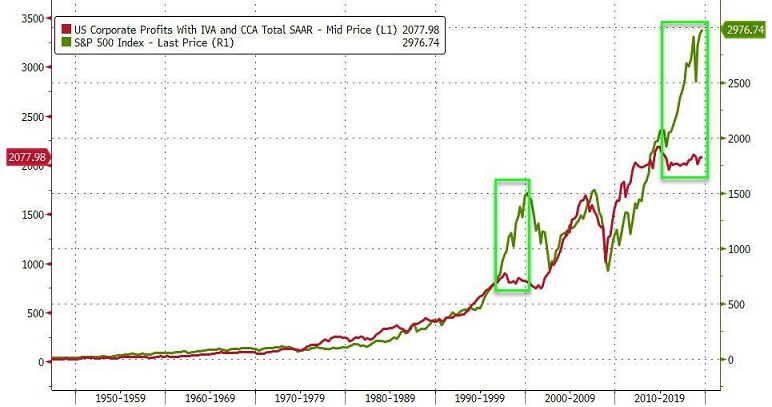

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times (to quote Charles Dickens)- for investors generally the former prevailed but for Hedge funds (and bears) it was the latter, as all asset markets surged higher. The year began with gloom as the Fed’s Quantitative Tightening started to bite and liquidity was being systematically drained from markets, resulting in a big fall at the end of 2018. That appeared to be enough to shake the Fed and in early 2019, Jerome Powell announced an end to QT (as it came to be known) and began the process of re-liquifying world markets. The result was immediate and long-lasting. Over 2019, global equity and bond markets added $24 trillion to market value ($17.5 trillion to equities, $6.5 trillion on bonds), with strong returns for nearly all global asset markets.

After the initial sharp rebound in Q1, equities traded broadly sideways as Trade War headlines dominated investors thinking. As seemingly endless “on again, off again” stories concerning a deal between the US and China emerged, markets paused, apparently unable to decide how this was to conclude. There was talk of reciprocal tariff impositions, which led to a 6.4% fall in the S&P 500 in May. But Powell’s comments (above) resurrected optimism as slightly below par earnings outlooks from several bigger US firms (Apple and Tesla amongst others) allowed investors to anticipate more interest rate cuts, with June seeing a 7.1% monthly gain, its best return in that month since 1955).

As of the end of September 2019, the US 20 Year Treasury Index was outperforming the MSCI World Index (+20% versus +18%), a highly unusual event, demonstrating that the rising tide of liquidity had lifted all boats. Another “precautionary” rate cut of 0.25% in October (the third of the year following those in July and September) helped this process along further.

Going into Q4, several risk factors were facing investors, all of which were avoided. The threatened imposition of tariffs on China (scheduled for December 15th) were not implemented, as a “phase one” trade deal was announced (though it still has not been made public, let alone signed) and the Conservatives won the General Election handsomely, removing the threat of widespread nationalisation of UK utilities (offsetting the loss of our free broadband!). The expected passing of the Withdrawal Bill implies that little will change at least until the end of 2020 in terms of trade between the UK and Europe means that the worst case scenario has been avoided (or at least postponed).

Finally, despite dire economic warnings (and an inverted yield curve, which has traditionally heralded the start of recession), job growth remained decent, with US jobs growing by 20,000 in November and business survey readings remained positive in both Europe and the US. An economic slowdown has probably occurred, but market participants retained their confidence that Central Banks stood ready to intervene if needed, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts.

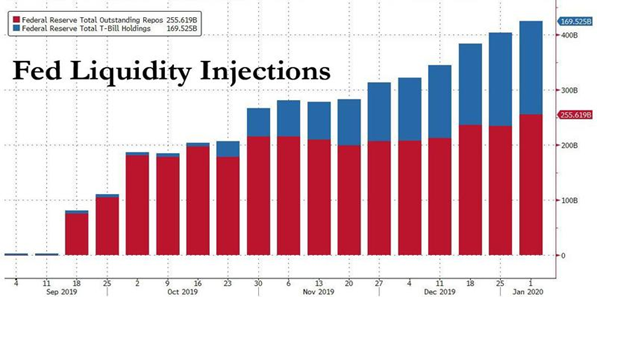

As year-end approached, there were concerns around money market liquidity, focussing particularly on the repo (repurchase) market, as rates at one point rose to over 8% in September (versus the target rate of 1.25%), which led to the Fed intervening once again, providing funds to the banking system, both via buying T-bills and repurchase agreements (see here for how this process works). It was supposed to be simply to cover year end funding issues for banks and brokers, but repo operations on 6/1/20 totalled $259 billion, versus $256 billion at the end of 2019, suggesting that the addiction to Fed intervention continues. In the last 10 weeks of the year, the money supply fell in only one week (November 13th), which was the only week in that period when equity prices fell.

It was a good year for nearly all markets and asset classes but a great year for some.

For example, the Shanghai Composite Index had its best year since 2014, the Dax in Germany since 2012, the S&P 500 since 2013 and the CAC 40 (France) saw its best gain since 1999. The FTSE All Share Index had its best year since 2013, as the General Election of December 2019 finally brought some measure of clarity to the Brexit saga.

Further afield, Asia and Emerging Markets saw lower gains in equities, but better performance in bonds relative to developed markets. MSCI Asia (ex-Japan), Emerging Markets and the Japanese TOPIX all saw 18-19% equity returns, well below their Developed markets equivalents, but EM debt returned 14.4% in 2019, double that of the US and Europe. After being up almost the whole of the first Quarter (and then again in Q3), the US Dollar fell back to unchanged for the year in December, giving EM investors a big sentiment boost (as a stronger Dollar makes it harder for these firms to repay their USD liabilities). Given the widespread negativity displayed by investors with regard to EM debt (particularly those denominated in local currencies and to a lesser extent in USD), a strong rally caused investors to buy aggressively to avoid missing out on gains.

In bonds, 30 year US Treasuries saw their biggest yield fall since 2014 and 2 year notes (which are more sensitive to interest rate cuts) saw yields drop the most since the depths of the 2007-09 financial crisis. Overall, US Treasuries returns a respectable 6.9% (with Europe also up 6.8%), but UK Gilts saw an 8.8% return (beaten only by Italy’s 11% gain) as a combination of Sterling strength and overseas investment flows pushed UK assets higher following the Conservative’s victory at the polls. Global Government bonds rose by 5%, held back by those of Germany (+4.3% and Japan (+2%) as investors seemed to prefer positive yielding bonds.

The outperformance of Corporate, as opposed to Government bonds was fuelled by the money printing by Central Banks, as risk assets were sought- Global Investment Grade bonds saw gains of 11.5% in 2019, slightly outperforming Euro High Yield (+10.7%) but well below US HY bonds, which rose 14.4%; this was at least partly due to US oil companies, who are large constituents of the US HY sector, having a good year, as oil prices (West Texas Crude) having been at $45 a barrel at the start of 2019, reached $63 a barrel by year end, its best year since 2016.

Not to be outdone, precious metals also had a good year, with both Gold and Silver seeing their best returns since 2010, rising 18.5% and 15.5% respectively in Dollar terms.

Looking at factor returns, there was very little dispersion between World Momentum, Small Cap, Minimum Volatility and Value, with all rising by between 21.4% (Value) and 27% (Momentum), again pointing to liquidity rather than individual factor characteristics dominating trading.

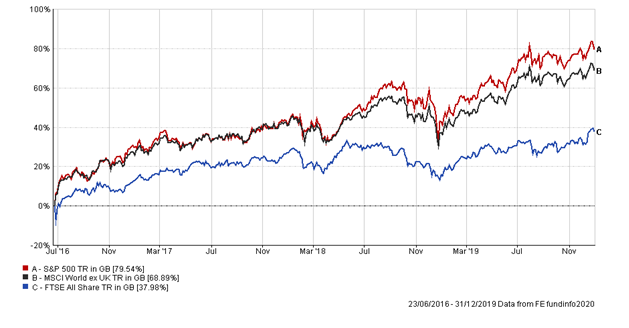

One might have imagined that the resolution of the Brexit chaos would have led to a narrowing of the return differentials between the UK All Share index and that of the rest of the World and so there has been- in Q4 2019, the All Share Index was up 4.16%, compared to the MSCI World ex-UK’s return of just 0.91%. But as the next chart shows, this improvement is barely discernible since the time of the original Brexit vote. As the withdrawal negotiations have not yet begun meaningfully, a UK bias is still hurting investors. It may be too early to say whether this trend has turned in favour of the UK bias portfolios, but the likelihood of a complete reversal of the past underperformance looks remote- something fundamental appears to have changed.

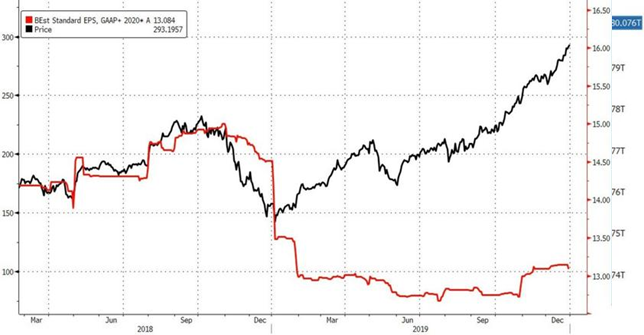

As the next chart shows, markets moved in lock-step with money supply growth and when in the summer Powell stated that the Fed “would act as appropriate to sustain the expansion”, the markets took off anew, as the “bad news is good news” narrative once again took hold.

This led to some seemingly bizarre situations- most notably in Apple shares, which gained $550 billion in market capitalisation in 2019, its best year for a decade, whilst Earnings per Share estimates fell by nearly 20% from the peak in mid-year. But it was by no means the alone (see below).

How big a move was it for markets in 2019? Using data from FE and looking out over the first 19 years of this century, with regard to returns and volatility, we can calculate that the 28.8% rise in the S&P 500 was a 1.4 standard deviation event, which has an approximate 8% chance of happening in any one year (or one in around 12). The MSCI World Index, which rose 27.67% in 2019 (its best performance since 2009) saw a 1.53 standard deviation move, which represents a 6.3% probability, (or 1 year in 16). Investment strategists, having gone into the year rather bearish, were thus blindsided (once again). Naturally, they are now scrambling to raise their year-end 2020 forecasts to catch up with actual price moves, suggesting that they will keep up their almost impeccable record of predicting the next years’ market moves with their usual one year delay.

Post Script: in January 2019, Jack Bogle, the founder of modern day Index investing died. He lived long enough to see his dream of passive investing becoming mainstream fulfilled and his legacy was best summed up by Warren Buffett.

“If a statue is ever erected to honour the person who has done the most for American investors, the hands-down choice should be Jack Bogle”

Mr Buffett is wrong- ALL investors owe him a huge debt. There should be statues everywhere.