“If you’ve been playing poker for half an hour and you still don’t know who the patsy is, you’re the patsy.” – Warren Buffett

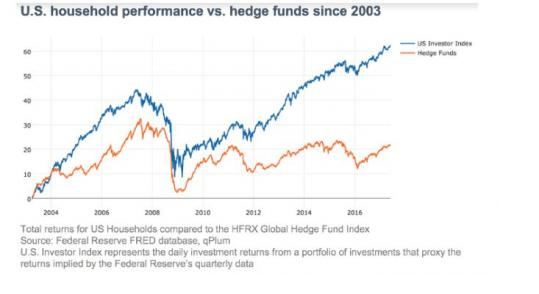

It has long been conventional wisdom (within financial “professional” circles at any rate), that Retail Investors are the “dumb money”; they buy at the highs and sell at the lows. Indeed, some professional traders actively seek out these investors, looking to push prices lower to ensure that they panic and sell at what turns out to be low points, dubbed “stop hunting”. Thus, retail investors are treated with near contempt by these traders, as being unsophisticated and prone to elementary mistakes, from which the gods of trading of course do not suffer. However, this view has taken a bit of a beating in the last few years, such that there now appears to be (in the US at least), an inverse relationship between the level of “sophistication” of the investor and their investment returns. An article in Market watch , suggests that, since 2003, US Households returned nearly 3 times that of Hedge funds, at 4.5% per annum, versus +1.6% for the latter [1].

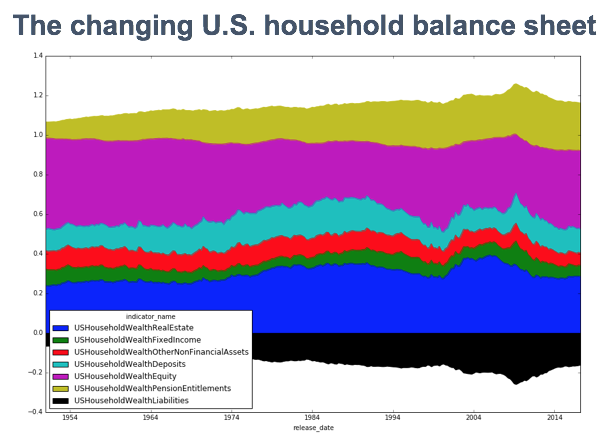

Why might this be? The authors of the study (G. Chakravorty and A. Sinha) cite two major factors; they don’t day trade and they dont chase performance [2], resulting in low portfolio turnover. They are also far better diversified, with exposure to bonds,equities and real estate. The latter was formerly the mechanism through which households saw growth in their total wealth, but that role has now been taken over by equities (see below), especially post 2009 as home loans became more difficult to obtain. Thus, the proportion of total wealth in Real Estate has fallen from 34% pre 2008 to around 24% now. In contrast, equities now represent 35% of total assets, up from 30% pre 2000, (but down from 38% at the peak of the Dot-com bubble).

Compare and contrast this with the attitude of Hedge fund managers; they take huge positions in a very small number of shares, both bullish (and occasionally bearish) with no risk-offsetting holdings, which lead to enormous blow-ups from time to time, (in this case Pershing Square was the “victim”). Furthermore, as investors they seem to suffer from “group think” problems, as they all crowd in the same stocks, dubbed “Hedge fund hotels” by some. Goldman Sachs have helpfully created an Index that tracks this phenomenon, which many now use to bet against Hedge funds themselves; when bad news strikes, they all rush for the exit simultaneously. And so this sort of thing happens, on an almost continual basis (note the surge of volume in the chart below -at the lows- as they all frantically try to exit).

As AUM (Assets under Management) ebb away, both egos and Investor’s net worth are battered. They have access to the best information, research etc. but it doesn’t seem to help, possibly because so many others have the same. Increasing complexity embedded in their “models” only serves to make things worse, as a sense of (false) confidence is generated in what is a dynamic and evolving process. So when it fails these “Smart people” are constantly surprised. Maybe individuals should be managing their money…

This may be related to the psychology of risk- one cannot avoid it (unless one does not need a return), but since individuals don’t have to trade every day, they can take a longer view and since it is THEIR money on the line, risk of loss is far more salient (as there will unlikely be anyone to bail them out of their mistakes!). The latter is more important to them than “uncertainty”, which is merely not knowing what the future holds. The near-impossibility of “beating the market” has now become widely accepted (as seen in the growth of Passive/Index fund asset flows), and has led to a “set and forget” attitude to portfolio investing- which may also explain the extraordinarily low level of market volatility of late. None of this applies to Hedge funds, as their focus is absolute returns, which requires them to do something, if only to justify their high fees. They believe, (because their livelihood depends on it), that they can beat the market and often use leverage to try to do so. Hence, the probability of catastrophic failure is increased; but the demise of LTCM and the “Too Big To Fail” doctrine has taught them that others will bear the losses should they become “systemically important” (which is a euphemism for large). Behaviour once learned and reinforced becomes ingrained very quickly.

At EBI we take this message on board completely. Our Portfolios are fully diversified, long term in nature, low cost and structured to be able to collect what the market gives us over time. We trade as infrequently as possible (the recent re-balance was only the second since 2014) and when we do, it is merely to take advantage of mean-reversion (which posits essentially that what goes up will come down and vice versa). Ironically, once one is confident that our portfolio can handle whatever happens, that one can cope with risks not paying off all the time, an investor can actually take the risks involved in markets which is what leads to major investment gains. Our clients seem to have faith in the future, such that fear is not the guiding principle behind the process of investing. After all avoidance of risk also implies avoidance of opportunity.

[1] True, the S&P 500 returned c.9.5% p.a. over the same period, but these investors took half the risk of the Index, giving risk-adjusted returns of a similar quantum.

[2] It has always puzzled me why assets become more alluring as they appreciate, rather than the reverse. I have never met anyone (outside of the City) who waits for prices to rise before they buy at the supermarket. I often wonder if a shop that operates “reverse Sales” in the Square Mile wouldn’t prosper on that basis!

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.