“There is man in his entirety, blaming his shoe when his foot is guilty.”

― Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot

I feel a sense of unease about posting this blog; memories of economist Irving Fisher’s (in)famous quote about stock prices being at “a permanently higher plateau” less than one month before the start of the Great Depression haunts me somewhat. If the Dow is at 15000 in the next two months, you will not see this blog, (or me probably) again…

A whole Cottage industry has arisen in the last 10 years, predicting that the “overvaluation” of equities will lead to a crash. (If you don’t believe me- type “Market Crash 2017” into Google: I got 6,500,000 results!) As the market continuously rises, it has not curbed this enthusiasm; indeed it is becoming more and more stridently assured of its own correctness. It is conventional wisdom that these high prices will lead to poor returns (at best) or a collapse (at worst).

Obviously, these forecasts have so far been disastrously wrong. What if their analysis is in error? What if the US markets are NEVER going back to those valuation levels? Selling in that scenario would be the height of folly, (though maybe not as bad as recommending others to do so).

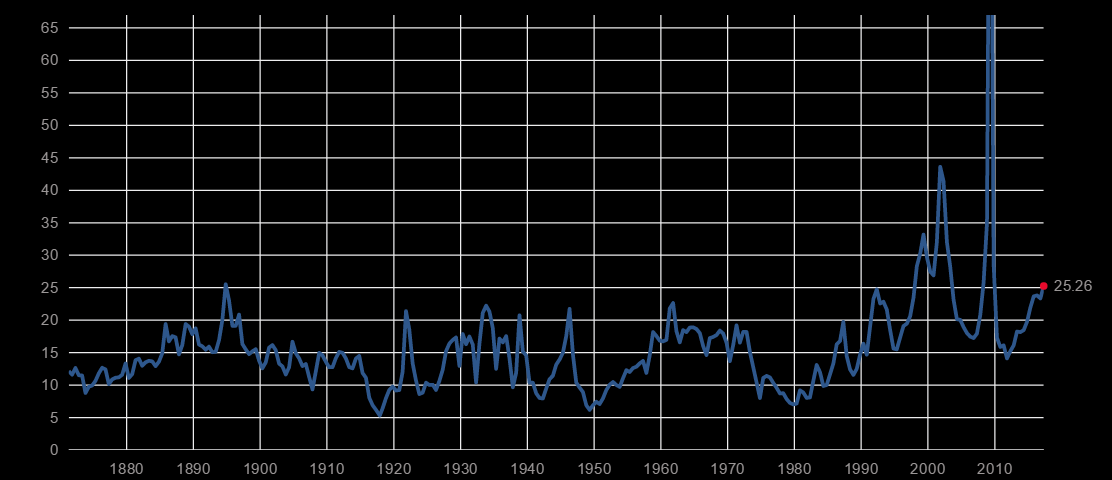

Consider the chart below. The pre-1997 average P/E in the US was 13.95 x. Post 1997 the average has been 23.3 x, and it is rising again above that point at the moment. The financial crisis of 2007-09 lead to its decline to the pre-’97 average for only what looks like a minute on this chart, followed swiftly by aggressive buying. It is thus possible that what was once the average is now the floor!

What could have caused this upward shift?

One theory advanced recently (here), is actually quite mundane (and thus extremely plausible): in the US, there has been a major change in the way clients pay for Investment services. In 2005, around $198 billion in assets were managed on a fee basis – that number today is around $1.29 trillion! Freed from the need to advocate trading (to generate commissions), advisors merely invest the money that rolls in on a weekly, monthly and yearly basis, almost regardless of the news (either good or bad) [1]. Knowing that longevity is rising, they decide that equities (and not bonds) are the way to go for clients. Who are the beneficiaries? Why none other than Blackrock, Vanguard, and the ETF providers, who have been raking in money, so much so, that they are literally struggling to cope with the volumes of paperwork involved. But it also means a continuous bid for equities, which may help to explain why declines are so fleeting.

One problem wth this theory though, as the author recently admitted, is that relentless does not mean endless, taking care (as I to my potential peril will not), to avoid the risk of being seen as a Perma-bull. As savers get older, they will need their money back, leading a relentless bid to become an equally relentless offer at some point in the future.

We thus may need to look elsewhere for clues and to do that, we must return to Stock market basics.

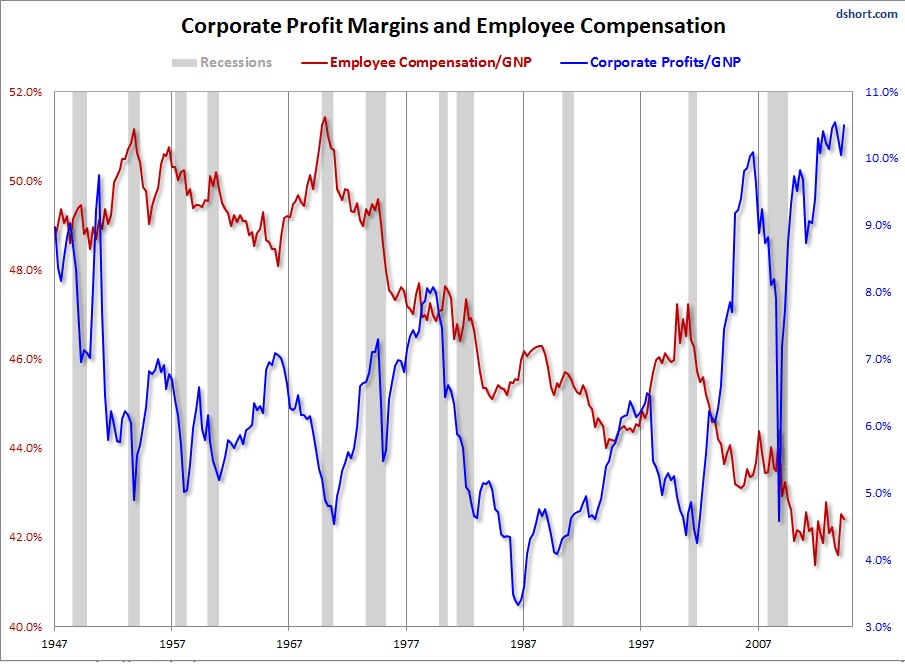

Three of the major inputs into Stock Market valuation are Corporate profit margins (the percentage of sales retained as profit), P/E ratios, (the value ascribed to those profits by investors) and Interest rates (used to discount future profits to shareholders). All three are moving in a direction which favors equity investors. The chart below shows how companies have benefitted in parallel with the decline in the fortunes of labour (the workers, not the party, though come to think of it….) As the share of income accruing to workers declines, Corporates benefit one-for-one assuming input costs (commodities for example) do not materially change. The chart above shows US that investors are becoming more and more confident that these margins will not decline anytime soon; with Interest rates at rock-bottom and showing no signs of rising significantly, combined with the higher level of Corporate leverage (aka borrowing), nirvana does not await but is the here and now. [N.B. Margins have fallen a little in the last 2 years: this chart only goes up to 2015, but they have not fallen below 9% since then and look to be rising again as of 2017 Q1].

How has this happened?

Three separate but related trends have emerged in the last 15 years or so.

1) Globalisation.

2) Increased Corporate power in both politics and law.

3) Lower Real Interest rates.

The first of these has seen an enormous reduction in Corporate costs, both directly (as Chinese workers, for example, cost a fraction of their Western equivalents to employ), and indirectly, as any firm who can credibly threaten to “offshore” work can keep a firm lid on wage costs domestically. Faced with this, Unions have been forced to concentrate on keeping jobs, rather than obtaining better wage rates. (It is no coincidence that Trade Union membership has been in continual decline in this period, as either workers give up on them or Companies have attempted to destroy them; the situation is no better in the UK).

Some have argued that the phenomenon of increased Corporate power has damaged Democracy. It is true that US Corporations have used their increased profits to tilt the playing field in their favour, especially the larger firms. Using their money to “buy” politicians has ensured that no incumbent parliamentarian will ever propose Bills that damage the interests of their donors. We hear a lot about how important it is NOT to undermine “business confidence” when proposing new policies, but that appears to be a euphemism for “don’t reduce our profits”. Over here, the Conservatives have suggested capping electricity prices in their manifesto, but Industry bigwigs have already started the softening up process- it in unlikely that this policy will be implemented in full or even at all.

The complete lack of jail time for any Bankers post-2007 (and the extraordinary indolence of global regulators with regard to City activity in areas as Libor, FX and Gold fixing, speaks volumes about who really controls the reins of power behind the scenes- is it completely unconnected to the enormous donations given by the likes of Goldman Sachs, Citibank, HSBC et al (to both sides of the aisle)?

Ironically, in order to “protect” workers, a whole raft of regulations have been brought in (think Minimum Wage rises, or closer to home, the FCA regulations on client protection), but Cui bono? The bigger firms of course, who can afford these cost increases; it is, in essence, anti-competitive, allowing these larger Firms to build “moats” protecting them from new entrants- as such, they are merely the cost of doing (or staying in) business. It may be no accident that according to the US Census Bureau, the number of new business start-ups between 2007 and 2015 has averaged minus 602 annually, compared to +98077 between 1998 and 2007. This would also explain the continuance of wide profit margins- the normal process of competition driving down profits to the marginal cost of capital has been short-circuited. The emphasis on profits rather than growth has led to a continual reduction in Capital Expenditure- so no serious competitive pressures have emerged. All of this implies a form of monopoly power has been created, as the bigger firms get bigger, and Multi-National Conglomerates dominate the World.

(Donald Trump came to office promising to reduce regulations on business, but this rhetoric has recently gone very quiet- has he been persuaded by Big Corporations that it may not be a good idea? If so, it may be a recognition on the part of Executives that regulations help rather than hinder their success).

Are there signs that this situation will change? Some point to the Brexit vote and Donald Trump’s victory as straws in the wind, but there is as of now no obvious revolutionary appetite in the UK or the US, so we may have to put away our pitchforks for a while. As such, the pressures on Corporations (and thus their margins) remain quiescent. Although there is an increasing anti-Globalisation movement in the West it remains uncoordinated and is by no means a major political force.

It is possible, (though not likely given the level of indebtedness both at a Corporate and Individual level), that higher interest rates will derail this trend; lower rates of population growth (which increases the bargaining power of workers) would also reduce profit margins, but both are going to take a long time to materialise, absent a political “revolution”.

Thus, what we have now we will probably keep; expecting a major market decline to allow one to buy at “bargain” levels may require the patience of Job. Of course, a 10% market decline could happen -that would be a normal occurrence- but 50-60% falls look like an extreme outlier event. That being the case, maybe we should stop fretting about market “overvaluation” and concentrate on the here and now. Like Waiting for Godot, it could be a long and frustrating wait for markets to mean-revert back to pre-2007 levels. Meanwhile, returns will inevitably be foregone.

[1] This phenomenon is now known by the acronym BTD (Buy the Dip).

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.