We talked about the failure of Global Corporations to invest recently (here), touching on the incentive structure that executives face in deciding whether to do so or not. Today we will discuss one of the major consequences of the lack of investment in new equipment etc. as it pertains to the Western world generally and the UK specifically. The glacial pace of productivity growth and its knock-on effect on living standards is becoming an issue amongst economists and is thus percolating down into politics. Every Minister, it appears, has a plan to close the “Productivity Gap”, but it remains stubbornly apparent. The Guardian blames (predictably) job insecurity, long hours, large pay gaps between staff and bosses, and a situation where too many are stuck on the minimum wage, leading to apathy and cynicism about job training and prospects. According to this article, many are just leaving their jobs, out of boredom or frustration.

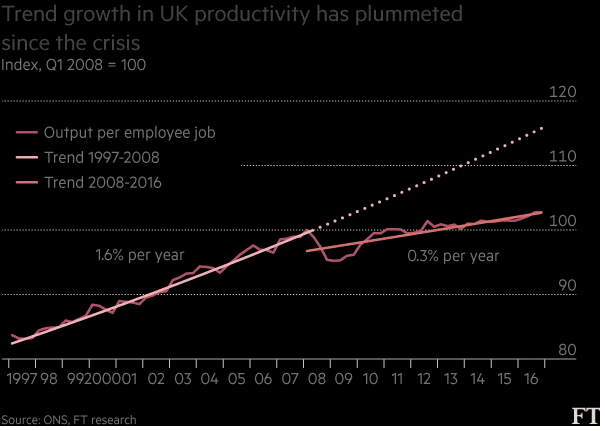

The FT (29/3/17) cites the Office for National Statistics (ONS) saying that 5 sectors are responsible for two-thirds of this decline; telecoms, electricity supply, legal and accounting services, management consultancy and Banking. The latter makes up only 4.4% of the UK economy but is responsible for 20% of the productivity fall, with average growth in this metric falling from 6.4% p.a. in the decade before 2007, to just 1% per annum since that time. However, there is some controversy, especially with regard to the data. Even the ONS is not sure of its findings: Nick Vaughan, chief economic adviser at the ONS, told a statistics conference last month that “parts of the service sector are not just ill-measured but completely mismeasured”. It is not just the Service sector either (where efficiency is more difficult to measure); manufacturing productivity growth has been in decline since the 1990’s. (see here) Still more worrying, neither off-shoring nor increased use of robots has done much, if anything, to reverse this process.

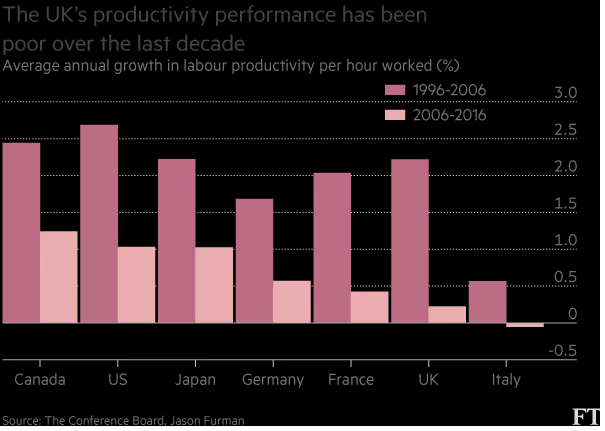

The charts below suggest that data quibbles aside, something really dramatic has been occurring, whichever way you slice it, as the UK is falling behind both in real AND relative terms, even in the face of a global slowdown in efficiency.

Some suggest that the solution is to raise wages; this paper suggests that if wage spending increases faster than spending falls from firms, there might be a net benefit (and I do mean might), or perhaps companies will raise investment to offset rises in wage costs. Too often, however, it merely leads to capital-labour substitution, US Restaurant firms are announcing layoffs to offset mandatory wage hikes and there is no reason to assume the same will not occur here. The basic problem is that profits accrue to (either) Capital, Labour or commodity inputs (raw materials). If one is not “productive” (however one defines this), it is difficult to see how one can expect a rise in pay (and thus living standards).

Alternatively, with the Western world ageing, there is a growing acceptance of the need for more immigration from Africa and the Middle East, where populations are young and growing, but as both Hollande in France and Merkel in Germany have discovered, this creates “a little local difficulty“, especially with elections looming. Indeed, Hollande has already given up hope of re-election.

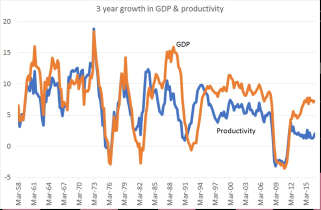

It is not clear what can be done; productivity improvements often takes years to manifest themselves in economic data. We are in a chicken and egg situation. Usually, (or at least in the past), faster GDP growth has led to higher Productivity growth, but this has not been true for nearly 20 years as the next chart shows. So there has been a breakdown in longstanding relationships and we have little idea of how to replace them. Possibly, the post-war period of strong productivity was a one-off event, which means that current growth patterns are the norm rather than the exception. But voters are getting increasingly fed up with the failure of “leaders” to address this in a satisfactory way, which only fuels resentment, leading to political instability, and thus lower business investment in a self-perpetuating vicious circle.

Markets don’t seem to mind much though. Whether that state continues depends on the results generated by firms. Income and Growth investors will be hurt if Company’s find profits hard to sustain, causing them to lower forecasts and ultimately cut dividend payments. The 85% outperformance of UK Value versus UK Growth in the past year hints that the market may be catching on to this possibility; interestingly, the IA UK Equity Income sector has performed almost identically to that of Growth over that same 1 year period, suggesting the same thing. The long-running nature of the previous outperformance of Income and Growth versus Value will not be unwound quickly or easily, as investors struggle to re-adjust positions to adjust to the “new normal”.

Given our well-established “tilt” towards value in our portfolios, this will presumably serve us well at EBI. But unless this paradox is resolved, markets may become less investor friendly than heretofore. Stay diversified.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.