“There are times when wisdom cannot be found in the chambers of parliament or the halls of academia but at the unpretentious setting of the kitchen table.” ― E.A. Bucchianeri

Summer is here and traditionally news is slow at this time, but an item on the BBC caught my attention last weekend. In it, the reporter stated that the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) had, according to it’s 2017 Accounts, a £17.5 billion deficit, rising by £9 billion last year alone, driven (they say) by lower expected future investment returns and lower Index Linked Gilt yields. Lecturers can relax, however, because although “Members may have seen a larger deficit reported in the media recently of £17.5bn. That calculation is based on accounting rules and is not the figure that drives the benefit and contribution decisions for the scheme” -so ignore all that accounting stuff and concentrate on the warm words! However, the report does mention that there may need to be a “re-calibration of the balance between benefits provided and the contribution rates payable”- you’ve just got to love executive speak!

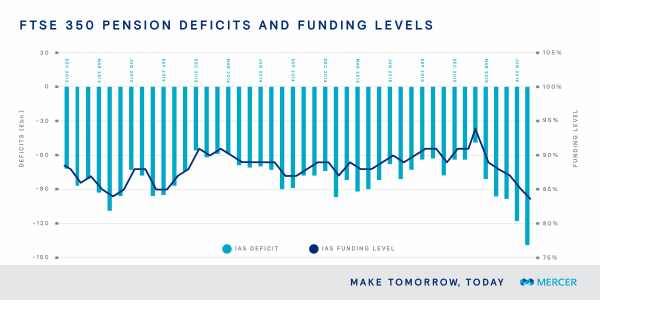

This is the largest deficit ever for a UK pension scheme and comes at a time when Bonds AND Equities are at or near to all time highs! [1].

How has this happened? Looking into the Report, (above) several things stand out; on page 45, it shows the asset allocation of the portfolio which is underweight in Equities generally (42.8% versus 62.5% for the “reference portfolio”) and is underweight in Index Linked Gilts (9.9% compared to 25% for the RP), offset by an overweight in “Nominal bonds” (i.e conventional fixed interest securities). Assuming that the majority of the latter was in Gilts, it could not have gone much worse as the chart below shows.

Add in the £2.2 billion invested in Hedge funds and £8 billion in Private equity, (p.75) and you have a recipe for this particular disaster.

The implications here are potentially huge- for one thing, Academics, who tend to be Left of Centre politically may find themselves unwitting participants in a form of socialism that they are not so keen on. Having only recently agreed to move to a career average scheme from the previous DB system, the prospect of higher contributions, lower benefits or a rise in tuition fees to cover this funding gap probably does not excite anyone, but scheme members (unlike their Local Authority cousins) do NOT benefit from the implied backing of the taxpayer, so could conceivably go bust, especially if they do nothing about this issue, relying instead on a gigantic “punt” on equities etc. (which then goes wrong again).

Another cause for concern may well be what this implies for other pension schemes, especially the Local Authority versions. Run on similar (amateurish) lines, they appear to have strikingly similar holdings, partly as a blame displacement exercise (as described in a previous blog post), but also a consequence of the “group think”, which is widely held in bureaucracies, for whom process always trumps outcomes.

Two of the largest, Greater Manchester and a previous employer of mine, West Yorkshire Pension fund regularly publish a list of their top twenty holdings. When we compare them to those of the USS, we see the same names crop up again and again. Ignoring Gilt holdings (see page 51), the largest holdings are in Shell, Roche Holdings, Samsung Electronics and Vodafone; Shell was (as of 2016, the latest year available, as the 2017 accounts are not yet out) the top holding in the Manchester fund and number 5 in the Yorkshire equivalent. Roche features in the former fund too (number 15), whilst the top twenty of the two Local Authority schemes have Glaxo, BP, Lloyds Bank, Rio Tinto, Unilever and HSBC amongst their number-this is just the top twenty holdings, so the degree of overlap between them is thus huge. We will have to wait for their reports to come out later in the year, but it is safe to say that if one has done badly, so too will the other (to say nothing of the other smaller schemes around the UK). These are £17 billion and £11 billion funds respectively- would (or could) the UK taxpayer bail them out if they get into similar difficulties? It seems rather doubtful.

The problem is global- pension funds, caught by the Central Bank’s zero/negative interest rate strategy are running into increasing problems, which are currently being downplayed (in France, Germany, but most clearly in the US, where the state of Illinois is poised to be downgraded to junk status as a result of its pension deficit and its refusal to do anything about it). At the Corporate level, the situation is similar, with US companies in potential difficulties, while over here, executives have opted to plug their scheme deficits by holding down pay awards, and by (successfully) lobbying MP’s to allow the potential suspension of Index-Linked benefit increases in order to close the widening gap between contributions made towards pensions and the actual cost of providing them.

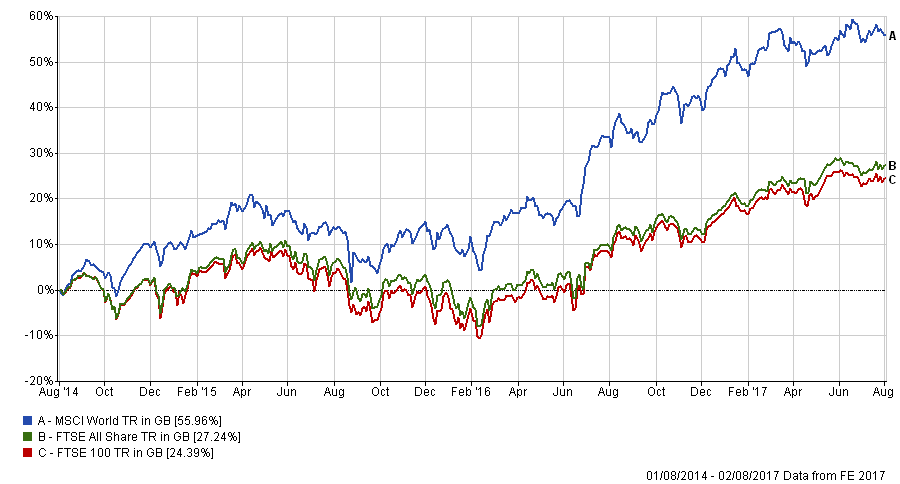

For other (more fortunate) investors the lessons are equally important; global portfolios reduce risk (via diversification) in an efficient fashion. The chart below shows the huge return disparity between UK and Global Equities in just the last 3 years (and in US Dollars the differential is almost exactly the same, indicating that Sterling weakness was NOT the main driver of this phenomenon). Those looking to provide for themselves need to ensure that they are not exposed to individual country risk (and with Jeremy Corbyn currently as low as 3/1 to be the next Prime Minister, this is a salient issue in the UK, possibly for the medium term).

At EBI, we are currently in the process of building global portfolios, which will have a much reduced UK weighting (c.6-7%) compared to the current Vantage weightings (as per the MSCI World Index). We will be offering these to clients as an alternative for those who wish to take action to reduce their UK exposure. If you have any questions, please feel free to contact us .

[1] According to the FT, (28th July) the 8 member Executive Committee was paid £3.9 million in bonuses and Long Term Incentives, in 2016-17, equating to £488,000 each. You really can’t make it up…

[2] This may be why, despite long standing conventional wisdom, a debate is now raging as to whether to transfer out of DB schemes, especially as transfer values appear to be rising. Whether one should, of course, is a matter for individual circumstances, but you can at least be sure that you will get the money if you do; it is certainly true that the Government is at least nominally committed to bailing them out should things go wrong, but the question may not be one of will, but of ability. Would it be politically palatable to do so, and could the State afford it?

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.