This is an up-date to a post I wrote a while ago.

“The investor’s chief problem – and even his worst enemy – is likely to be himself.” – Benjamin Graham.

It is late on a Friday evening, and my local pub is evincing a, ahem, somewhat liberal interpretation of the UK Licensing laws. So, I get two more drinks and settle back down into the corner of the bar to find my friend, (John) returning to his favoured topic, that of his investments and how well he has done since we last met.

J: Well, I have had a good run in recent months, despite all the market twists and turns of late. Only last month, I bought into Anglo American shares and made 10% in two weeks! Its gone down since, so I am feeling quite pleased with my efforts.

Me: Really? I remember that you also bought Barclays shares a while ago, how is that one going?

J: Not so well; but I think it will come back and when it does, I am going to sell out of it as it hasn’t done much. But I am only down 5% or so, so I will hold on for a bit.

[This is known in Behavioural Finance (BF) as the “Disposition Effect”, whereby Investors hold on to “losing” investments for too long and sell “winners” too quickly, in direct contradiction of the adage that one should sell one’s “losers” and hold on to the “winners”. The effect of this is to curtail gains and (potentially) magnify losses – one look at the General Electric chart shows how badly this can work out. It is related to the Regret Aversion effect, whereby Investors are reluctant to admit they have made a mistake by selling at a loss. Carillion investors have learned the hard way that total losses can result. Incidentally, it is part of the reason why Momentum works so universally as an investment strategy; people “under-react” to new information, meaning that they fail to recognise the longer term impact of both good AND bad news on a share price – hence trends, once established, go on much longer than investors expect].

Warming to his theme, John continues;

J: Of course, things have got a bit more difficult, what with Brexit and all, but it was obviously going to be a rocky time in the short term. The prospects for markets still look good, what with low interest rates etc, etc.

Me: Indeed.

[This is Hindsight Bias in action; very few investors predicted the result of Brexit, and even fewer made money on it, (as most drew bearish conclusions from their analysis). One can go back further, to the bursting of the Internet bubble to find “analysts” who knew it was all madness, but hardly any recommendations actually profited their clients, (and in some cases, their private views were much less flattering of the stocks themselves)].

With a final rhetorical flourish, John opines on what lies ahead;

J: I am quite optimistic about markets. Rising interest rates are a GOOD sign, as it suggests growth is picking up and I dont think the Central Banks want to crash the markets. Since I don’t expect any major declines, why would I not want to be involved? Its not as difficult as some make out – all you need is a bit of intelligence!

Me: Hmm. I am sure you are right, Central Banks DON’T want a market crash, but that has not stopped them in the past. According to Goldman Sachs, the Oil price and the Fed are the cause of most post World War II recessions. We shall see….

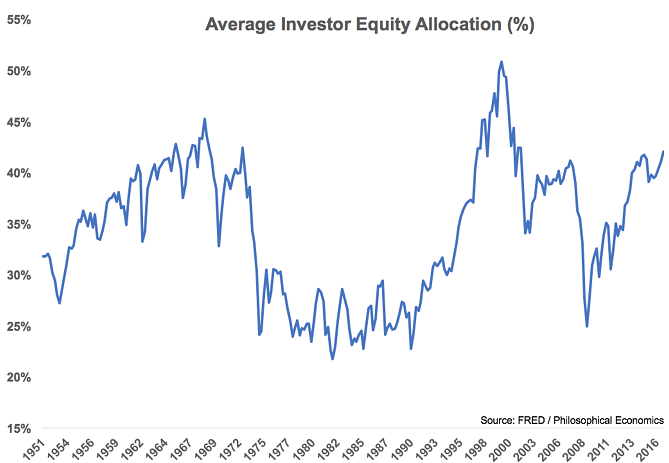

[Oh dear; this is over-confidence writ large! It is not at all clear how an “amateur investor” can compete in terms of knowledge (let alone speed of reaction), with a Professional investor who spends all day glued to his/her Bloomberg Terminal and has access to high-quality analytical data. As fund managers have found, (again), intelligence (of all sorts) is not anywhere near enough to survive, let alone prosper in one of the most competitive arenas known to man. This is consistent with Self-Attribution bias, whereby the investor’s ability is the source of profits, whereas losses are due to bad luck, (or market stupidity!). Naturally, if one does not expect a decline, one should buy shares/bonds/property etc. but on what basis can one ground that expectation? It is also a form of Confirmation Bias, as the investor looks for information that supports the initial investment thesis, whilst minimising (or just ignoring) data etc, that contradicts it. It is also linked to Recency Bias, which is the tendency of investors (and analysts) to extrapolate recent events endlessly into the future. Since we haven’t had a major market decline, there will not be one; it is why asset allocations to stocks reached all-time highs in 2000 and the lows came just after the 2009 lows (see below)].

This is by no means an exhaustive list, but the first step is being aware of them – only then can we avoid their pitfalls.

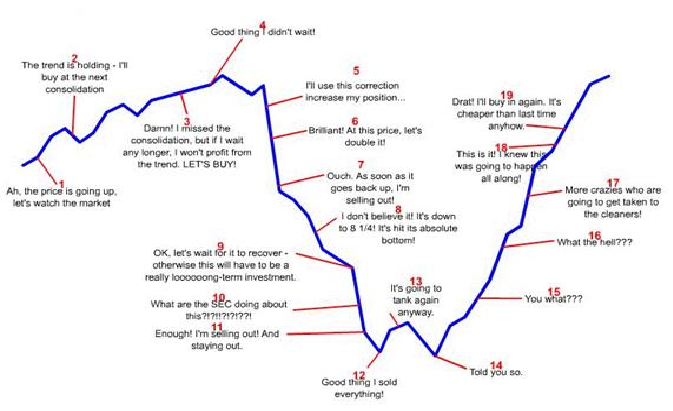

The below chart is an extremely good summation of the emotional roller coaster that the markets subject us to (if we let it!).

John of course is by no means alone in his errors. Investing is extremely difficult (which is why most investors under perform even the funds they invest in). It is also why an estimated 90% of traders eventually go broke. Active management is still by far the most popular route to investing, though that gap is closing fast, as large numbers of investors begin to recognise this reality.

So how does one take the biases out of the investment process?

1) Know one’s risk tolerance. There is no point in having a great portfolio if one cannot cope with downtrends. Markets will not oblige with continual gains for long (despite what 2017 appeared to teach us!), so one needs to be able to live with declines. Markets are not there for our benefit and returns have to be earned – this is done by accepting the risk of (potentially extended) falls in prices. If one cannot live with that reality, one must either reduce one’s risk exposure or not invest at all (which is a surefire way of earning no return).

2) Use a systematic approach to investing. Arrive at an asset allocation that one can live with (see above) AND STICK TO IT. It is the long term that provides the greatest returns (via compounding of gains), whilst the short term is more or less a lottery. As the market guru Mike Tyson, once said, “everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth”, but what he really meant was that things don’t always go the way one wants – the key is endurance in the face of adversity and how one deals with it.

“If you’re good and your plan is working, somewhere during the duration of that, the outcome of that event you’re involved in, you’re going to get the wrath, the bad end of the stick. Let’s see how you deal with it. Normally people don’t deal with it that well.”

I never thought that I would end a post with a quote from Mike Tyson…

Vanguard published a research paper as far back as 2013 to look at all these phenomena and their effects on investment performance. This is as good a place as any to start. Here is a list of the most common biases that investors (knowingly or not) have to contend with…

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.