After only the briefest of pauses post 2007-09, debt in all its forms is on the rise again and on a global scale; it now represents a staggering 327% of World GDP (or output). From Chinese state enterprises, to US Auto loans and here in the shape of consumer borrowing, debt is back and in a larger way than ever. As the chart below demonstrates, undeterred by Brexit, Trump’s victory or worries over North Korea etc, outstanding Credit Card debt is at all time highs (again).

.png)

There are two reasons for this state of affairs. Potentially, it is because consumers, companies etc. are extremely confident about their future, or, more worryingly, they are “distress borrowing” [1]. For Britons, it may be the latter. As the next chart shows, they are saving less of their income, as real wages continue to ebb away, despite record levels of employment. Are we borrowing merely to maintain our current living standards? If so, it does not bode well for the future. We shall find out soon enough I suspect.

.png)

But debt is a Global phenomenon; as the next charts demonstrate, both Corporations AND Governments are knee -deep in the stuff too. Indeed, the 2007-09 crisis marked only a tiny hiatus in debt accumulation and the near vertical up-trend has resumed. Of course, if growth is rising faster than debt, this creates a virtuous circle (whereby growth pays off the debt, leaving some profits/returns which can then be re-invested to generate more profits etc. etc. But growth is lacklustre (at best), meaning that the debt piles continue to grow.

In the case of Companies, much of it is being used to finance share repurchases – the ability to deduct Interest on debt for tax purposes is a strong incentive to do so (as is the need to reduce the dilution effect of executive share options)[2], but it may be on the wane, as some are now concerned that Corporate bond holders are taking the risk for the benefit of equity investors (since increased debt levels increases credit risk).

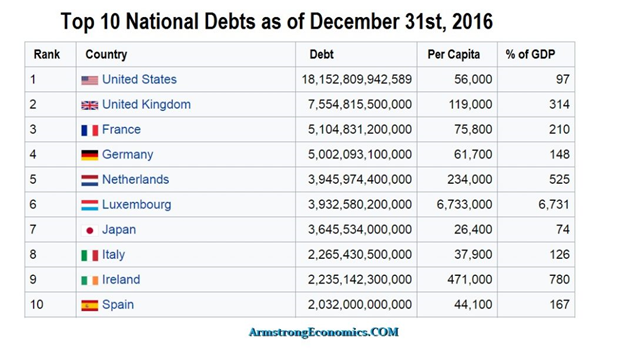

Meanwhile Government expenditure continues to rise inexorably, some of it discretionary (military spending in the US, or the HS2 project here in the UK), but some are not– healthcare, pensions and other age-related expenditure cannot be delayed for long and it is politically toxic to even suggest cutting it (as Theresa May discovered in July). The table below suggests the UK are one of the worst “offenders”, but none of them in truth are innocent. There is limit to the ability to tax Corporations (as they will just re-locate), which only leaves individuals as the potential bag-holders (not the rich of course, because they can leave too). So we should not be surprised to find the definition of “rich” becoming elongated to include those of previously assumed “average” incomes.

But what will that do to growth, investment etc?

This, of course, has implications for both Bonds and Equities; as I have been droning on about for weeks, it is another tailwind for the former and a potential headwind for the latter. In recent weeks, both the Fed and the ECB have been talking about the possibility of raising interest rates and/or reducing the size of their balance sheets (by selling back the bonds they have been buying continually for the last 5-6 years). The childish tantrum thrown by both German Bunds (-3%) and US Treasuries (-2%) in the space of a fortnight since those comments have been enough to force both of them to backtrack, underlining once again that almost any de-leveraging would put enormous pressure on both markets and (to a lesser extent) on the real economy. Given that Central Bankers have exhibited zero tolerance for market declines, it is pretty clear that this means more market intervention; we could be back to where we started in 2007. And so, QE5 becomes the next obvious step, which would pass the performance mantle back to equities, in a repetition of the previous cycle.

It seems that we are at an impasse- debt leads to economic slowdown, which leads to Central Bank buying of bonds (but maybe equities too, as have the Bank of Japan and the Swiss CB), which leads to gains for equities, as money is used for portfolio re-balancing purposes. So, trying to second-guess, or “time” market movements will likely be a futile (and costly) exercise. The high degree of nervousness exhibited by market commentators does suggest many are concerned by developments, but there is little mileage to be had by trading in or out of asset classes. Maybe this process repeats in an infinite cycle?

At EBI, we have just completed a portfolio re-balance (selling out of Emerging Market equities in favour of bonds), but this is NOT a statement of where we think markets are going- it is a risk reduction response to the large out-performance of EM since the last process was instigated (when we were buying EM). Maintaining a constant exposure to our desired asset mix ensures that we do not have to take a view on their performance-we let the markets do that for us. It worked like a charm last time (August 2015) but only time will tell if this latest iteration fares as well. But even if it doesn’t, our clients will at least know that we are not over-exposed to one particular region, asset class or sector. That way, sleep comes much more easily…

[1] More common in recessions, it implies that debtors are engaging in one “last throw of the dice”- borrowing in order to buy time, hoping that something will turn up- it rarely does.

[2] To see this , imagine a company with profits/dividends of $100, and 1000 shares outstanding . Each shareholder then has $0.1 of earnings attributable (100/1000). If the CEO then awards himself 100 shares via options, the number of shares outstanding rises to 1100. This means that the same amount of earnings must be shared out between a higher number of shareholders, so the resulting EA is now 0.0909 (100/1100). In order to offset this dilution, the company buys back 100 shares (effectively from the executive himself) to bring it back to $0.1. Seemingly a win-win (if you ignore the obvious!). This has been going on for a long time, in massive scale, but in a bull market, investors don’t seem to have noticed (or cared). Ending the tax-deduct ability of interest for companies, would be a game-changer, but as this would probably lead to sharp declines in equities, it is highly unlikely to be proposed anytime soon.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.