“Whoever has the sword will have the earth.” – Oliver North.

The “Matthew Effect” [1] is a term coined by the Sociologist Robert Merton to describe how eminent scientists get more recognition for their work than do less well-known researchers and thus get more funding and so on in a seemingly virtuous circle of success. A similar story appears to be playing out in asset markets, too, with the US seemingly impervious to bad news and now homing in on new all time record highs for both the Dow and the S&P 500 – the NASDAQ Index managed that last month. But the laurels are not being shared equally as the following charts show. Year-to-Date, there have been some big fallers, particularly in less-developed markets and the MSCI Emerging Market has, over the last 10 and a half years been trounced even by the dunce of the developed world class, the FTSE All-Share Index.

It looks even worse at a sector level. According to Goldman Sachs, 60% of the growth in US profit margins are due to the IT Sector, (implying that the bulk of the markets’ constituents have seen no margin growth at all!), as a result of the rise of “superstar tech firms”, whilst some sectors (below) can’t seem to get a break. Banks in both Europe and Japan are still below pre-Lehman levels. Since January 2001, the FTSE 350 Bank sector has lost 14.25%, an astonishingly bad performance – it can’t ALL be Fred Goodwin‘s fault!

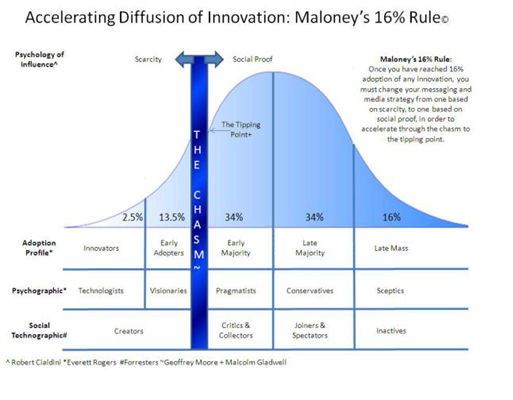

Why has this happened? A number of reasons can be cited, including share buy-backs, which we touched on previously, which have been concentrated in the big Tech firms, the extent of buying into these same firms by big Institutions (including Central Banks) alongside other world-renowned investors, (together with the famed reluctance of those same firms to pay taxes), but these do not explain the extent of the divergence between Tech and non-Tech share price returns. It may be that we will have to look beyond conventional economics and go into the realms of marketing or more precisely, Innovation Theory. It has its most immediate relevance in politics but the same process may be occurring in Tech and more specifically Tech firms.

In the early 1990’s Geoffrey Moore postulated that there are nearly always one in 6 people (16%) that are willing to adopt a “new thing” (whatever that is), but the challenge is to get beyond “the chasm”, (c.16% adoption) for the idea/product/theory to become mainstream [2]. At this point the message has to be about “social proof”, i.e. join the group because everyone else has, rather than how great the product etc. actually is. Mass adoption comes when people’s “shared experience and community” is accepted. The growth of the Internet/Social Media fits this precisely and explains why large proportions of the population cannot seem to live without Facebook, mobile phones, and other technology-related paraphernalia. Once that position is reached, there is little likelihood of its being dropped, to the enormous benefit of firms such as Netflix, Amazon etc. as they create “economic moats”, so beloved of Warren Buffett. This, in turn, creates a “Winner Takes All” market structure, whereby a company that may only be slightly better than the competition but sees all (or most) of the economic benefits [3. Once the 16% rubicon is crossed, the sky is pretty much the limit for both companies and those leading them.

This has certainly been the case with the US FAANGs shares (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google – now called Alphabet), which have dominated stock market performance in 2018; as of the end of June, the S&P IT sector was responsible for 102% of the market’s year-to-date return (though that relative out-performance has slipped recently, as both Facebook and Tesla have stumbled a little).

As a result of this process, income equality has also dropped sharply as the “winners” win more and the losers seemingly go backward, as the rise of the 0.1% gathers pace. Can this process go on forever? It would seem unlikely, but it took a Great Depression to turn this around in the 1930’s (which had seen similar levels of inequality) and that may not be the best way to achieve the goal. But we can prepare for change by ensuring risk is compatible with our ability to accept it and one of the best ways to keep that relationship stable is through re-balancing – as it happens, we are very close to implementing an EBI Portfolio re-balance (UK Bias suite) at present (see here – login may be needed), as a result of the surge in (mainly US) equity prices. Assuming it goes ahead, we would be selling (International, ex-UK) equities in favour of Global bonds, which would have the effect of “de-risking” the portfolio somewhat. At present, the Vanguard Developed World ex UK fund currently has a 63% exposure to US equities (all of the top ten holdings are in US shares) whilst the Global Small Cap fund has a 56.9% US equity weighting. If and when the re-balance is triggered it will involve a significant reduction in those exposures, such that any decline in the dominance of Tech, will be muted. Similarly, the Russell 2000 Index (the US Small Cap benchmark) has made a succession of new all time highs this month. So, reducing the EBI weighting, though counter-intuitive to some, is a sensible precaution against market “exuberance”. We think it is eminently sensible to sell (some) of these positions (i.e. take profits), while we can. The alternative is doing so when we must, which is most often after a serious decline. This will take us back to our desired weighting, to be at the risk level with which we (and our clients) are comfortable.

[1] As per the New Testament parable, “to those that have, more will be given”.

[2] This idea was expanded upon by Chris Maloney, a marketing expert, to form his “16% rule”.

[3] This theory can also explain why political parties either rise to power (the Northern League in Italy rose to power, reaching 28% support by June 2018, whereas UKIP in the UK, dwindled to irrelevance post the Brexit referendum, as Nigel Farage assumed his job was done. Donald Trump won the Presidency in the US (at least partly) by convincing enough minority voters to give him a chance, something that Democrats never believed was possible. We now have the prospect of a real-time test of this phenomenon in both Germany (with the AFD) and potentially in Sweden, with the Swedish Democrats; can either of these gain enough support to earn “social proof”, and thus get into Government?

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.