Blog: Solving the dividends puzzle

Company boards in every country are scrambling to conserve cash, comply with strings attached to state subsidies and performing pivots, if not pirouettes, between the short and long-term interests of a gaggle of stakeholders ranging from employees, investors, bankers and underfunded pension funds. Among energy companies for example, Shell have just cut their dividend whilst BP are holding out. Dividends in this environment can hardly be viewed as anything other than a highly discretionary signal from company managements to their stakeholders.

Some of our clients are worried about dividends too.

Here is our recent COVID-19 Investment Update Q&A with a very pertinent question about dividends for a client’s investment committee:

What should investors do about income funds which rely on dividends, given the needs of companies to protect their own solvency, and pressure from central banks to compensate by reducing dividends?

At EBI Portfolios we typically evaluate equity investments on the total return basis, independent of dividend policies selected by the boards of underlying company holdings. The Income, as opposed to Accumulation, classes of portfolios are available where investors require an income to be paid separately from capital returns.

Empirical evidence, since a famous study (1) by Nobel laureates Merton Miller and Franco Modigliani, suggests that at least in theory, dividend policy should be irrelevant to stock returns. Around two thirds of US stocks and just under half of international stocks do not pay dividends at all, so it would impact our ability to benefit from diversification if such stocks were excluded from consideration.

Quantitative researchers love to group distinctive characteristics into “factors” and study their collective behaviour to draw comparisons. Studies have determined that the dividend yield factor is closely allied to existing known factors such as Value. Dividend strategies are also allied to profitability, investment and quality factors, of which more below.

For a different perspective, behavioural economists (2) explain the ‘preference’ of investors for cash dividends in terms of choice behaviour – problems delaying gratification, and prospect theory – differing views of perceived gains and losses. Some investors choose to rely on income streams from dividends rather than “cutting into capital” and selling securities to meet expenditure requirements.

Taxation is another friction that can rationally impact the decision-making process and the decision to take capital gains or income must be weighed using appropriate tax advice.

So, from our investment point of view, whether you take the dividends or sell capital your total returns will be identical.

Hopefully, this explanation should cover most bases, but there are distinct characteristics around dividends in relation to investor tastes which we can explore further.

As bond yields have been compressed by the central bank and state interventions such as Quantitative Easing (QE), some investors have scrambled for yield. Many have now moved from chasing bond coupons (often moving up the credit risk spectrum) to chasing high equity dividend yields.

The extent of an investor’s appetite for regular dividends can change over time owing to any number of drivers. It can depend on whether you are living off investment income in retirement. It might depend on the level of regret you feel about taking a home-made dividend by selling stocks or units in dividend funds.

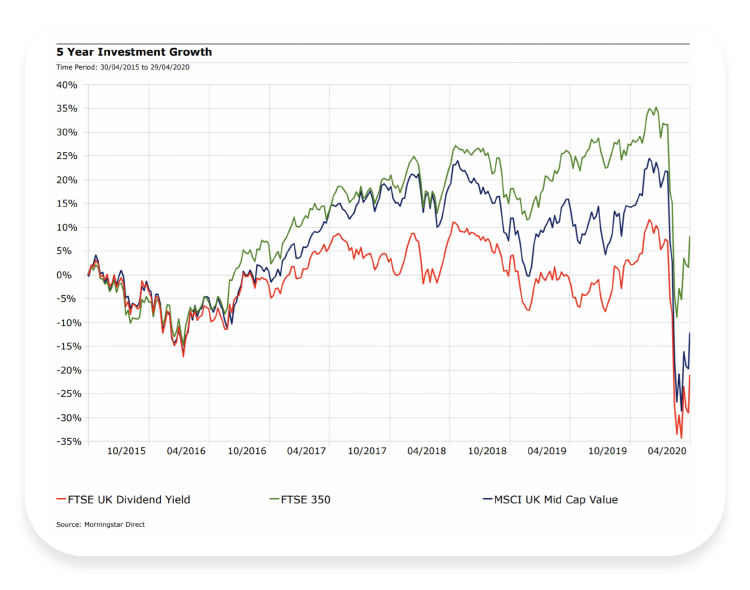

Sadly, for those UK investors who look at the world solely through the lens of dividends, recent performance of the FTSE UK Dividend Index, which measures the performance of the 50 highest yielding companies in the FTSE 350 Index, has not been impressive.

Five-year performance has lagged the FTSE 350 Index by -20.25%, and even underperformed the MSCI UK Mid Cap Value Index by -7.22%. I’d caution that this is just one observation point in time to take a reading. I have only considered a five-year period ending in the recent crisis, which as the client question above expressed, can be expected to impact dividend-paying stocks disproportionately.

Dividend Yields As A “Factor”

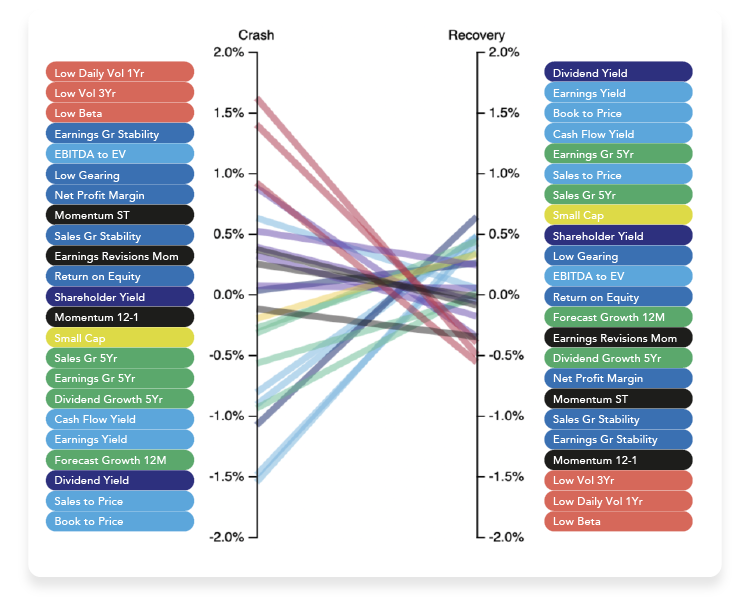

Considering dividends from the perspective of factor characteristics, there seem better prospects for the dividend yield factor at least in the short term. Performance of the dividend yield factor during past market crashes and recoveries such as the GFC makes it look attractive if you’re trying to time factors.

In their recent research article (3), Style Analytics find that Value style sub-factors (coloured in blue in the two diagrams below) and the Small Cap factor (coloured yellow) suffered very poor performance during the GFC and 1987 crashes but subsequently enjoyed the best recoveries. It’s a similar story for the dividend yield factor which rebounded in the GFC from one of the worst performances during the crash, not unlike the Value style sub-factors, to achieve the best recovery.

One issue that muddies the water is the relationship between dividends and share repurchases better known as ‘buy-backs’. Research suggests that dividends and stock buy-backs are more or less substitutes for each other and that corporations are relying more on share repurchases now than before. In fact, for the US, buybacks exceed dividends in recent years.

Studies show the cash flows received by (pro rata) buyback investors and cap-weighted index investors are ostensibly the same, despite the first group of investors receiving their returns through buybacks and the second group relying on dividends (4). Companies, notably banks and industrials, cut repurchases aggressively during the last crisis (5) and might be expected to do the same again this time.

So, what use can we make of insight and information contained in dividend yields? Dividends seem to divide investors sharply between those like EBI who believe in total return approaches and those that seek dividends. According to one study (6), increased demand from investors seeking cash from dividends drives values higher and lowers expected returns for many securities. Other studies suggest individual investors have a marked preference for dividend stocks compared to institutional investors, whose aversion falls in low interest rate environments.

In the factor investing arena high dividend characteristics spill across several factor groups. They are traditionally viewed as part of the Value umbrella but are also included as one of the sub-groups of the Quality factor. One recent study, What is Quality? (7), evaluates the net payouts, taking into account both dividends and stock repurchases or buybacks, as one of seven categories grouped under the Quality banner. It finds net payouts (dividends and buybacks) one of the most robust (statistically significant) of the seven aspects considered (8).

It seems that whichever way investors consider them, the relevance of dividends has not gone away yet. Whilst interest rates and yields remain low, some investors will chase dividends, company managements will puzzle over whether they can afford to declare them and factor investors will continue to regard them as a valuable metric to watch.

(1) Dividend Policy, Growth, and the Valuation of Shares, Merton H. Miller and Franco Modigliani, The Journal of Business (1961).

(2) Explaining Investor Preference for Cash Dividends, Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman, Journal of Financial Economics (1984).

(3) Factors in Stock Market Crashes and Portfolio Recoveries by Damian Handzy, PhD, 2020, Style Analytics.

(4) The Long-Run Drivers of Stock Returns: Total Payouts and the Real Economy, Philip U. Straehl and Roger G. Ibbotson, Financial Analysts Journal (2017).

(5) Payout Policy through the Financial Crisis: The Growth of Repurchases and the Resilience of Dividends, Eric Floyd, Nan Li, Douglas J. Skinner Journal of Financial Economics (2015).

(6) Equity Duration: A Puzzle on High Dividend Stocks, Hao Jiang and Zheng Sun (2015).

(7) What Is Quality? Jason Hsu, Vitali Kalesnik and Engin Kose, Financial Analysts Journal (2019).

(8) Payout as well as dilution signals are significant contributors to the quality factor in all regions studied with the notable exception of Japan.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.