“The fact that there’s a highway to hell and only a stairway to heaven says a lot about anticipated traffic numbers.” – Bill Murray. (re-quoted from The Price of Everything blog).

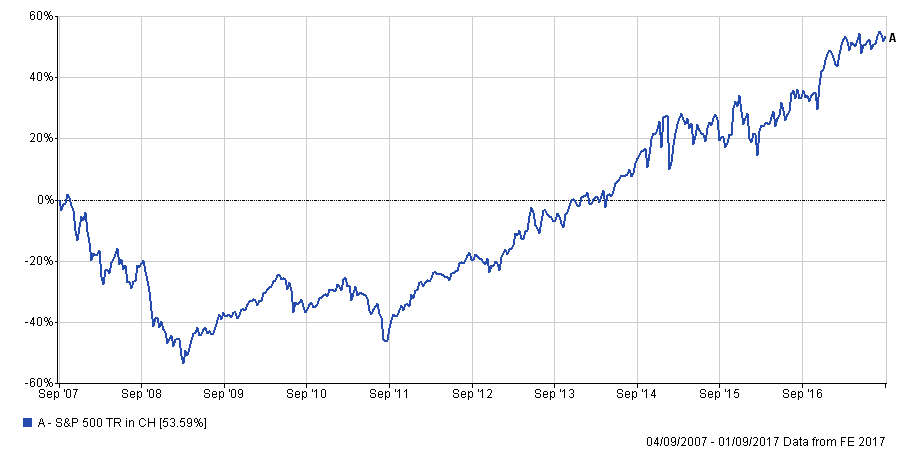

It is well known and understood that currency hedging programmes are extremely useful in immunizing portfolios from the effects of base currency appreciation. If your base currency is Zimbabwean dollars (to take a rather extreme example), of course one would not need to do so, (as presumably the whole point is to escape Zim $), but for most others the situation is less clear cut. It may not become pertinent for UK investors in the next few years, (especially if Corbyn gets his electoral wish), but has been a live issue for others over the last decade, notably the Swiss and before them, for the Japanese as they saw their domestic currencies rise almost inexorably for several years. (See charts below highlighting the damage done to Swiss investors by the Franc’s rise over the last decade).

Vanguard has issued many papers re: bond hedging, one of which is here. Not everyone agrees with their view however; the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth fund (which looks after the country’s Oil proceeds), has (per the FT from 5/9/17), decided to increase equity exposure across its portfolio, but also to reduce currency diversification within its global bond portfolio. “In the long term, the gains from broad international diversification are considerable for equities but moderate for bonds. For an investor with 70 per cent of his investments in an internationally diversified equity portfolio, there is little reduction in risk to be obtained by also diversifying his bond investments across a large number of currencies,” the fund wrote in its letter to the ministry of finance in Oslo.

.png)

What is more controversial is the view on whether or not to hedge equity exposures; conventional opinion posits that this is unnecessary, because it tends to be the case that (unlike with bonds), equity volatility is higher than that of FX (Foreign Exchange). With bonds, it is entirely possible that a portfolio value gain can be wiped out by currency changes [1], whereas a similar eventuality is considered less likely in an equity portfolio. (Though recent declines in equity volatility may in time change that opinion, if it is sustained).

Vanguard have weighed in here too, as have others and the conclusion appears to be “it depends”, (which is not massively helpful). So, in what circumstances would be a good/bad idea? [For the purposes of this discussion we shall assume that the base currency is Sterling].

Good idea:

1) If the investor strongly believes that Sterling will rise; overseas portfolio valuations will be negatively affected by that occurrence, since hedging converts the foreign currency return into a Sterling return 1:1. This of course is attempting to predict the future and seems to be self-defeating-if one knew with certainty that sterling would rise, there would be no rationale for overseas investment!

2) The investor is underweight in GBP assets; but if so, surely one should just buy more sterling assets?

3) To reduce overall portfolio volatility; this appears to be laudable aim, but will only work consistently if the correlation between foreign currency and foreign equity price moves are low. As one may expect a stronger foreign currency to lead to weaker equity prices (as it makes that country’s exports more expensive) this may well be a valid reason to do so, but these relationships are apt to change with no warning. For example, in a situation where global investors are buying into a perceived “sure thing” (think the Internet bubble in the US), a US Dollar rise is an effect of that enthusiasm, not a cause and thus has no effect on equity returns for currency hedge portfolios.

On the other hand, it may be a bad idea when:

1) Investors have a long time horizon (at least 10 years); as Goldman Sachs Asset Management points out (above link), long term returns of both hedged and non-hedged portfolios are similar, as currencies tend to “mean-revert” (and any differences are purely a function of interest rate differentials).

2) If an investor is overweight in local (in this case UK) assets; as many investors still exhibit a “Home bias”, they are in effect overweight in the domestic currency. In that instance, having exposure to Yen, Euros or Dollars may well aid the process of portfolio diversification. Of course, this assumes that..

3) Returns to overseas equities are lowly (or ideally negatively), correlated to the returns available at home. This may or may not be the case. According to FE, 20 year rolling correlations between the S&P 500 and the FTSE All Share are at 0.8 presently, but between the latter and the Japanese TOPIX Index only 0.51 (in Dollar terms the correlations are 0.82 and 0.56 respectively). Thus, an un-hedged approach will improve the diversification benefit of owning foreign equities if their correlations are lower than that of their respective currencies with respect to the domestic equivalents.

From the above it should be clear that we at EBI do not support the idea of hedging foreign equity portfolios, (though we do favour hedging bond investments overseas). This is why we do not do so in the Varius equity fund; we seek the returns of foreign equity markets and use bonds to dampen the overall potential volatility inherent therein; [as an aside, we struggle to formulate a scenario under which sterling sustainably rises under any realistic situation, though that does not rule out gains over a shorter timescale, as appears to be happening now-the current environment may be more a case of Dollar weakness rather than sterling strength though]. See US Dollar Index chart below.

Diversification is not a free lunch. It does not protect against market (Beta) risk or ensure profits; of course, one quick (and cheap) way to reduce the currency (or any other risk) exposure is to have less exposure to that asset in the first place, which is where risk tolerance and asset allocation comes in. Currency hedging can be thought of an insurance against a negative event and its’ purpose is to put oneself back in the same financial position that existed prior to the occurrence of the event in question; if one is seriously concerned about an alien invasion (which judging by some world events recently may already have occurred !), or a stock market crash, or a currency collapse, it my just be easier to have less risk to that event. In other words, do less hedging, because there is less risk to hedge!

This has the added benefit of reducing market impact and trading costs, which can be larger than anticipated, especially in times of market stress, which is of course when everyone else is ALSO trying to “hedge”. As long as the asset allocation is in line with risk tolerance, it is probably not worth the trouble (or psychological damage) to completely eliminate “risk”. After all, a perfect hedge makes you no money whatsoever…

[1] Bond market volatility is currently around 5-6% per annum, whereas Foreign Exchange option prices indicate an implied future volatility of 8-9%; in contrast, equity volatility regularly gets over 20% and much higher than that in times of market stress (though the recent torpor of the VIX Index has been well documented).

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.