Up-Date to a previous blog; at the end of October, we discussed the recent travails of the Hedge Fund community (here). We will very shortly find out how bad it could get; this article picks up on the theme and points out that Investors who wish to redeem their HF holdings have to give 45 days notice of their intention to do so. So, November 15th is the deadline to get out (penalty-free), for year-end. After another really poor year and the likely shock of seeing October’s (lack of) returns, many could decide to head for the exits, which could (theoretically) scupper any chance of a year-end rally (as Hedge Funds could be forced sellers).

After a period of relative inactivity, the Dollar is once again on the march. Having traded sideways for 6 months, it has once again advanced to just below 97, and is nearly 5.5% up this year, mainly at the expense of Emerging Markets currencies, but is up versus the Yen (1%), the Euro (+6.2%) and Sterling too (+4.7%). The reasons are not hard to divine – Interest rate differentials are on the rise as the Fed seeks to “normalise” monetary policy, whilst the other major central banks are seemingly “trapped” at or near zero, possibly afraid of the consequences for growth if they tighten (and of who will buy Euro government bonds once the ECB stops doing so).

According to the most recent Commitment of Traders report, speculative traders are short all three of the major currencies against the Dollar (though in all three cases nowhere near the extremes of the last 3 years), leading to some seeing a bullish consensus, (which is of course bearish for the Dollar). But are traders really so bullish on the US currency? The Euro crisis (Italy, Immigration etc.), the on-going stagnation in the Japanese economy and a spot of bother in old Blighty regarding Brexit leaves little alternative to the US Dollar as a viable home for institutional money; further, from a traders viewpoint, it is very expensive to be short the Dollar, as Interest rate differentials (which, to a trader is a fundamental input into the decision making process), are strongly pro-Dollar as the chart below shows. As the Gold line indicates, over a two-year view, the Euro would have to rise by 3.5% per annum versus the Dollar for a Euro buyer to break even, (as the interest costs on the Dollar short position eat into profits) [1].

.png)

This situation pertains at all time periods; using the link (here), we can see the (annualised) Libor Euro and Dollar interest rates for one month; currently, Dollar rates are 2.30663% and those of the Euro -0.41086% (yes, you have pay to lend money in Euros!). So the cost to borrow USD is thus 2.30663 + 0.41086 = 2.717% on an annual basis, which is 0.377% on a weekly basis. At the current FX rate (1.1271 per Dollar), the Euro would need to move to 1.1313 just to cover the financing costs. There is an adage in Foreign Exchange that is if a currency is too expensive to short, then you buy it; that seems to be what they are doing.

We can see the same stress in the Cross Currency Basis Swap market (which is another source of funding for both banks and Corporations) [2]. In the Euro/Dollar CCBS is currently around -0.5%, (see below for an explanation of this), which implies a major shortage of Dollars available to borrow.

As a result of this, Financial Conditions are tightening, as it becomes more difficult to borrow Dollars, partly because everyone else is trying to do the same thing. (See our blog of 2/11 for more on how this Index is created and what it tells us). It is thus no surprise that equity markets are struggling (and Mr. President is not happy at all!). With the currency near 17-month highs (and 40% of the revenues of S&P 500 firms emanating from outside the US), neither are corporate executives; some analysts fear that profit margins (and thus earnings) may have peaked, (which explains the broad sell-off this week). The ending of Quantitative Easing (QE) and it’s replacement by QT (Quantitative Tightening) as the Fed tries to reduce its balance sheet size, means that this process will likely go on until other Central Banks follow suit, which in the case of both Japan and Europe looks a long way distant.

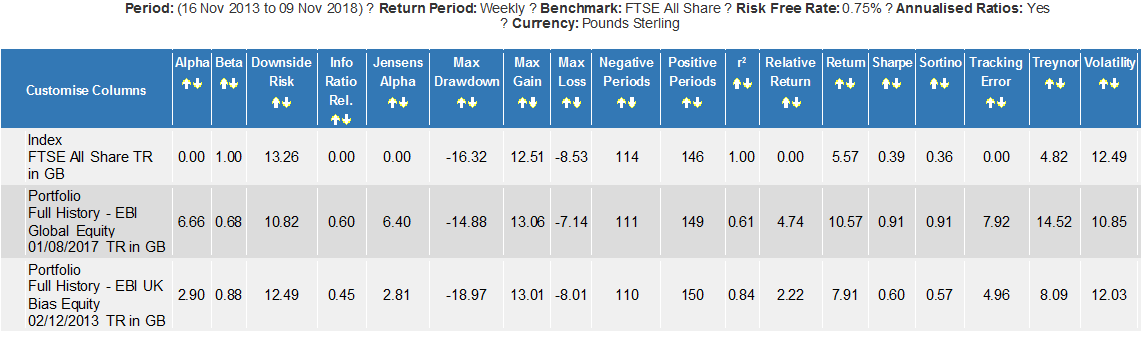

From an investor’s vantage point (no pun intended) it is important to be aware of the effects of a US Dollar rise on EBI portfolios. From a Bond perspective, there is little direct impact (as all bond holdings are hedged to Sterling), but equity funds are not hedged. Thus, the more one is invested Globally, (which in practice is mostly in US assets), the bigger the potential gains from this process (even if we ignore the benefits of better diversification). Below shows the 5-year Dollar returns for EBI 100 (Global and Home Bias portfolios). When translated back into Sterling, the returns are greatly magnified. In GBP the corresponding returns are 63.56% (Global) and 46.34% (Home), doubling the investor’s gain. Of course, this is not going to occur every year, but if the above interest rate differentials are not to erode (via a 1-2% Base Rate rise by the Bank of England?), it is hard to see this situation changing in the short/medium term. So, for an investor in Global portfolios, Sterling weakness is to be welcomed (not feared), as it boosts the GBP value of assets held in other currencies (though the chart below features EBI 100 and to the extent that one is invested in a Home Bias portfolio, these benefits are diluted somewhat).

Regardless of one’s currency view (and we don’t have one!), the current situation is working out well for Globally focussed UK investors; Brexit issues are clearly weighing on Sterling at present, (though how long that lasts is an open question). In any event, owning a truly Global portfolio both substantially reduces Volatility and substantially improves returns, relative to the UK only-market (see below). In the abscence of foresight, this is the best solution to the conundrum that is asset markets.

[1] If one sells short a currency, you need to borrow it to deliver to the buyer; to borrow it costs interest on a daily basis. The higher the interest rate, the bigger the rise in the value of the currency required to break even.

[2] In simple terms, this trade reflects the cost of swapping a currency (e.g. Euros) into US Dollars (typically for 3 months); the price for borrowing US Dollars is purely a function of Interest Rate differentials between the two (as the two currencies are swapped at the same exchange rate at the beginning of the contract and at the end). In theory, the basis (or premium) should be zero, but when Dollars are scarce, it often trades at a price above the prevailing differentials. 3-Month USD rates are 2.61413% and those in Euros -0.35814%, giving an expected cost of borrowing Dollars of (2.61413+ 0.35814= 2.97% per annum). However to get the actual cost one must ADD the 0.5% swap rate cited above to the 2.97% to get 3.47% on an annual rate. This makes it very hard to see how one could make a profit by being short US Dollars as a trader in the FX market.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.