Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.

In the last month, there have been a number of stories featuring Corporate “malfeasance” (as the Americans would call it) or normal business (as Jeremy Corbyn would no doubt describe it). The curious feature of it is it’s timing – looking through history, scandals tend to occur at or near the end of a Bear market (Buffet’s “tide”). For example, the Enron scandal broke in October 2001, both Tyco and Worldcom filed for bankruptcy in July 2002, near the October 2002 low; Lehman Brothers failed in 2008,the same year as Bernie Madoff was uncovered as a fraudster. India had it’s own version in 2009 when Satyam‘s President confessed to cooking the books.

But this time is different – with the Dow Jones only down 17% peak to September trough, (and now back around 17000), the media knives are out and the hunt for corporate villains is in full swing. If one looks hard enough, one can find nearly anything, but several stories have surfaced in quick succession.

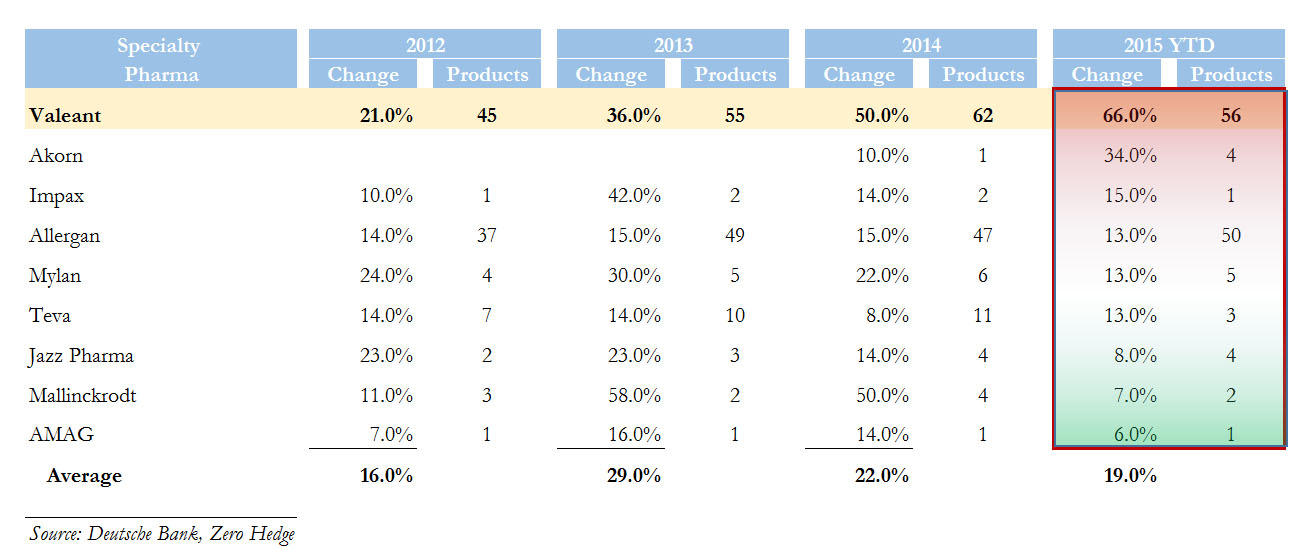

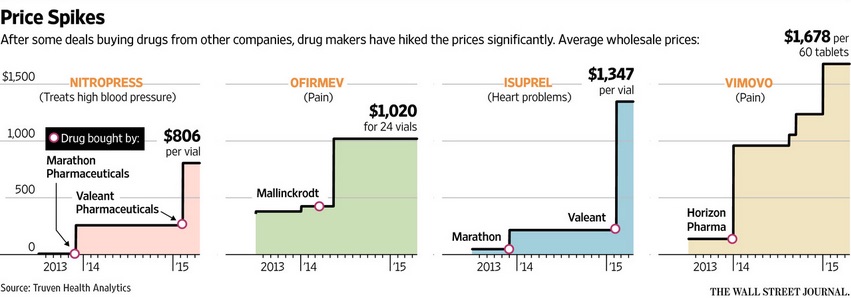

In late September, Martin Shkreli the CEO of Turing Pharmaceutical hit the headlines after his firm bought the rights to a drug used to treat immune deficiency problems and promptly raised the price from $13.50 per tablet to $750 (a mere 5000% increase). His claim that the drug was “still under priced” was greeted with derision, and he was forced to backtrack, promising to lower the cost to a more affordable level, but did not specify when and by how much it would fall. A former hedge fund Manager, he fits the archetypal profile of a corporate wrong-doer. But in an ironic twist, two days later an American short seller brought out a report claiming that Valeant Pharmaceutical was even worse (obviously to justify their short position thesis).

Predictably, the share price promptly collapsed 25% in a matter of hours. Attention then turned to other big pharma companies, and Pfizer, along with Merck, were promptly vilified in the press, with politicians rushing to jump on the passing bandwagon.

The industry was not helped by the confluence of these price rises and the merger frenzy that has been on-going for the last year or so, as the next chart highlights.

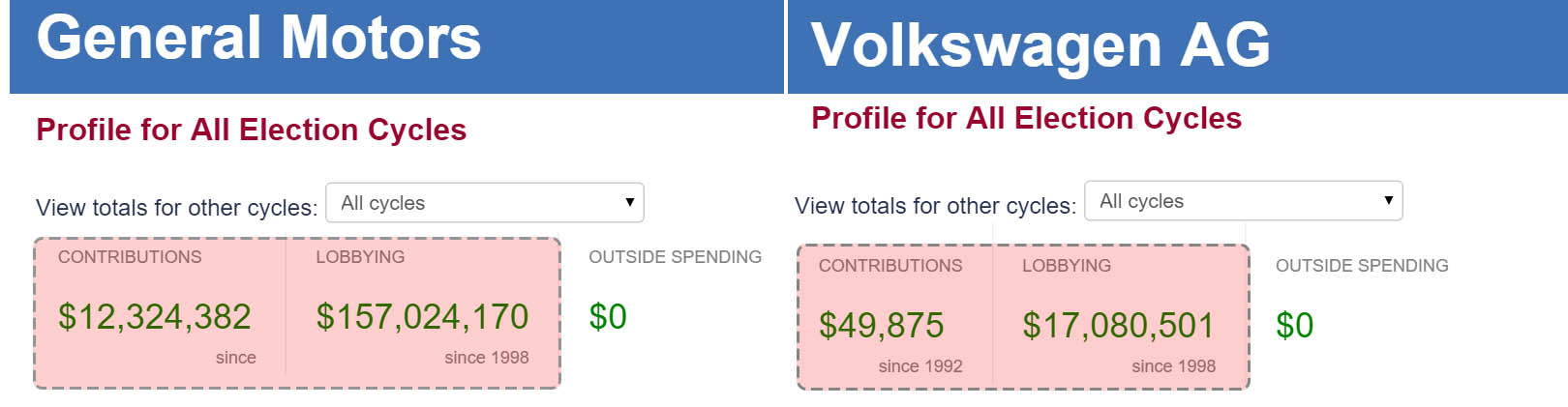

Then, at the end of September, it was discovered that VW had faked test data on diesel emissions in the US. Bloomberg reported that BMW (and Audi, Seat and others) may well be implicated too. Ironically (or not) as the Washington Post reported, General Motors had hidden an ignition-switch defect which may have caused 170+ deaths. However, no employees faced criminal sanctions and the company paid a fine of $900 million, whereas VW may face an $18 billion fine. As the chart below shows, the share price plummeted, continuing the fall from the March 2015 highs.

Cynics might point to the differing “investment” strategies employed by the two car-makers (according to Open Secrets), which may explain the different treatment…

Why does this sort of thing happen ? Being the head of a (global) business is highly pressurised; the rewards are high, and the pressure to succeed is relentless. Competitive advantage, the elixir of corporate life, is fleeting, and getting more so in the Internet age, where news, innovations etc, travel across the globe in minutes. Thus, the temptation to cut corners to gain or maintain this advantage is always there, especially in the “winner takes all” compensation structure that currently exists.

But other factors may also be at play. Experts (of all types) fail to get it right on a consistent basis, and the CEO of Turing Pharmaceutical may have just failed to anticipate the furore his decision would cause. A reluctance on the part of subordinates to be the bearer of bad news may have led to an isolation from events on the ground, leading him to believe there would be no reaction (which there wasn’t for 7 months!). What seems like a good idea in theory can quickly turn into a PR disaster. This is probably true of the whole Corporate sector, and the lack of an instant reaction probably increased their confidence that nothing was amiss. This, of course, can rapidly escalate into a form of overconfidence. Since overconfident people (as studies have consistently shown) are rated by others as more competent than they really are, they are often able to pursue policies that might not be company-optimal: confirmation bias then allows us to filter information in a way that ignores contradictory evidence, thus perpetuating the initial problem. Think Fred Goodwin…

It is possible that this is all random noise. It is axiomatically true that these events are unpredictable and there is no reason that three of these scandals could not occur in rapid succession, especially as two involve the same sector (pharma). In a sense, they may not be truly independent events since many of the actors are responding to perceived future strategies of other players – some of them may be in a sort of prisoner’s dilemma where they have an incentive to get their “retaliation” in first…

If, on the other hand, this is part of a generalised trend it has implications for investors beyond the actual share price falls. It once again underscores the stock-specific (or idiosyncratic) risk that they take in markets. In the high frequency trading age, even a small amount of diversification may not be enough. As this article points out, not only did investors with individual holdings get hit, but some ETFs did so too. Of course, this is impossible to predict a priori, so the only realistic response to be as widely diversified as is possible. Combining this with re-balancing (which is a form of enforced diversification), will not reduce the chance, but the impact of Black Swan events in the future.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.