Evolution consists of two simultaneous but quite separate phenomena of adaptation and diversification- Ernst Mayr (Evolutionary Biologist).

Everyone (or nearly everyone) understands that the more assets one owns, the better the chances that errors (which we all make), do not cause large, irrecoverable losses to a portfolio. This applies in equities, bonds and property, but what may not be quite so apparent is that this is a necessary, but not sufficient criteria for successfully diversifying risk. In order to achieve an efficient portfolio, the assets one owns should be as un-correlated as possible, such that they respond to different factors, thus reducing idiosyncratic risk, namely the risk specific to that company or issuer, (unlike market risk cannot be so easily diversified away).

This train of thought flows from Modern Portfolio Theory, which emphasises the importance of the risk-reward trade-off (higher risk means higher reward) and that the aim of a rational investor is to achieve the highest reward for a given level of risk (or equivalently, the lowest risk for the same level of reward).

How does this work in practice?

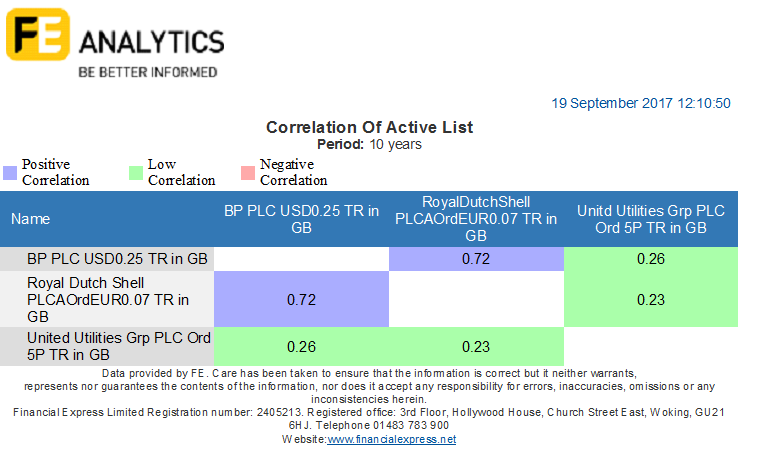

To take (an admittedly extreme) example, the chart below (from FE) shows correlations between three (not so) randomly chosen equities, namely BP, Shell and United Utilities. As one can see the correlations between the two Oil majors are high (0.72), which implies that around 52% of the change in price of Shell is caused by movements in the price of BP (and vice versa). In contrast, the correlation between Shell and UU is 0.23 (which means that 5% of the price moves in one of these shares is due to movements in the price of the other) [1].

Given a choice, a rational investor would prefer to combine the latter two shares rather then the former, as Shell and BP share prices clearly move in the same direction, reacting to much the same economic stimuli . There is thus no diversification benefit to owning the two oil companies, whereas by owning both Shell AND United Utilities, one could reasonably expect them to respond to different (and possibly opposite) factors. It can be mitigated somewhat by owning similar stocks in different markets (e.g. the US and the UK), but this only partially dilutes this effect- we dont invest in an ideal world.

Generally speaking any correlation above 0.7 (70%) is deemed to be high, whereas anything below 0.3 is said to be low. Obviously, if the correlation is negative that is even better (as it implies that the two assets move in opposite directions).

For Bonds, in addition to the above, there is the additional complicating factor of credit spreads to deal with. If credit spreads ( the difference between Government bond and Corporate bond yields) widen, this implies that Corporate bonds are under-performing the former (and vice versa if interest rate spreads between them narrow). This of course is difficult to forecast, so it is necessary to prioritise high quality corporate issues (as they are less likely to see significant spread widening ). Naturally, industry -specific factors can arise, (a major decline in the Oil price for example would have implications for Oil company cash-flows, leading to them becoming perceived as more risky), so again a broad allocation across different sectors and industries is appropriate, for the same reasons as for equities.

Diversification is said to be the “only free lunch in investing”, (a phrase attributed to Harry Markowitz ) and is key to establishing an acceptable balance between risk and return. Since bonds are generally lowly correlated with equities, they tend to offset negative price movements in the latter asset class and provide a “dampening effect” on overall portfolio volatility; as an example, a 60:40 (Equity/Bond) portfolio fell c.27% during the 2007-09 financial crisis period, compared to a 50% plus fall in an equity-only portfolio. Whilst the former return would be painful, the latter could be terminal in terms of an investor’s financial survival. It therefore behoves investors to protect themselves from the worst case scenario,- these things CAN happen (and not just to other people!).

In our Varius bond portfolio, we have over 23000 different bonds (though some are from the same issuer), from high quality credits (an average of between A and AA), only c.40% of the portfolio is invested in Corporate bonds wherein “spread risk” lies) and an average duration of 4-5 years, meaning that the fund has limited exposure to both Interest rate AND credit risk; this ensures that the portfolio does its job of dampening overall portfolio risk.

Returns are lower than for conventional bond portfolios due to latter’s higher duration (see one of our previous blogs for an fuller explanation of this phenomenon), which increases the risk of price falls in the event of interest rate rises. As the chart below shows, duration globally has been rising steadily for most of the last 20 years.

According to one analyst [2], more than 90% of the total return from US Investment Grade bond portfolios have come from interest payments rather than price changes; this is due to the fact that higher rates allows the investor to re-invest maturing bonds at higher rates than previously. Thus the shorter the maturity of the bonds, the quicker one can take advantage of the higher rates being paid, which is why we prefer to own shorter dated bonds, so as to take advantage of this reality.

[1] This explains it more succinctly.

[2 ] Williams, Rob. “Should You Worry About Bond Mutual Funds If Interest Rates Rise?” Charles Schwab Insights. 16 Sept. 2014. Web. 22 May 2015

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.