“Buy not on optimism. Buy on arithmetic” – Benjamin Graham

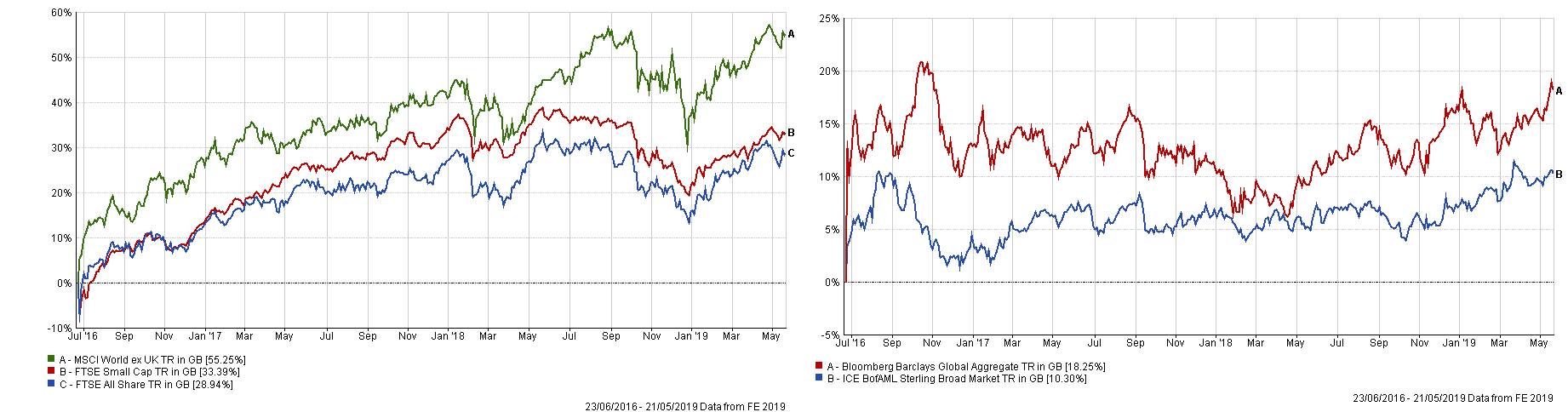

Analysts and fund managers rarely agree, but on one thing they are united; the UK stock market is cheap, at least in relative terms. Since the Brexit Referendum, the UK All Share Index has lagged the World (ex-UK) by over 6 percentage points per annum on an annual basis and now stands on a Dividend Yield of 4.22% (as of 17th May) and a Price Earning Ratio of 16.05x compared to 2.32% and 18.63x for the World ex-UK Index. There has been a flurry of articles proclaiming that the UK share market is cheap, [1], with a JP Morgan fund manager declaring that they have not been this cheap since World War One! The charts below show the damage wrought since the Brexit result.

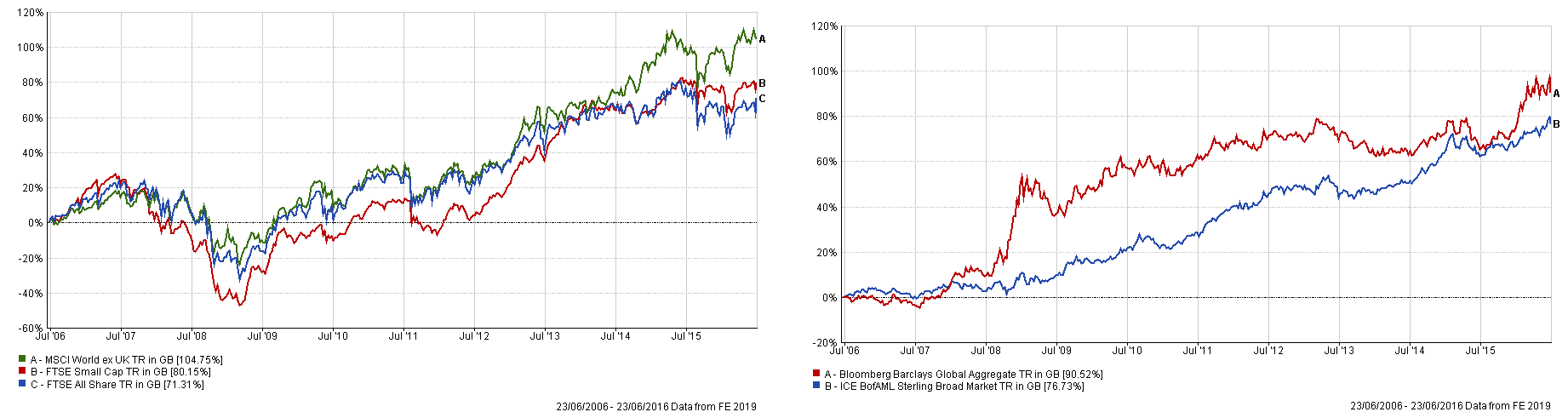

But is it a buy? The chart below suggests that not all of the underperformance can be traced to Brexit, as the returns gap began to open in the middle of 2014, so we must look for an alternative explanation for this phenomenon. It may be that the UK has become a value trap. We wrote a blog some time ago about the concept of a value trap at that point as it related to Bank shares – up-dating the charts shows that what seemed “cheap” then, has remained so, with the All Share Banks Index improving a little but still underperforming the All Share by 7.33 percentage points per annum since October 2008.

We can see the long term underperformance of UK plc vis-a-vis the World in the same light. It is impossible to say exactly what is causing this state of affairs, but something indisputably is doing so. The consequence is that the UK asset markets are increasingly being left behind by the rest of the world – it is clear that something is inhibiting investment into the UK and it is not only Brexit.

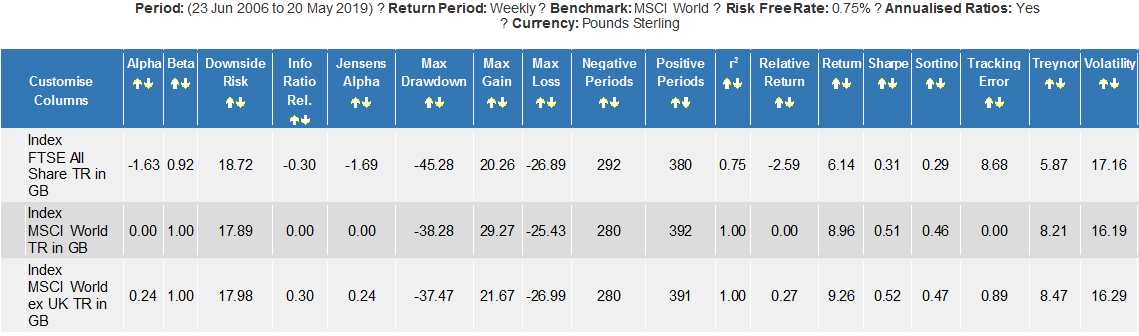

Looking at the Ratio Table from FE (below), we can see the All Share trailing on several metrics, including higher overall volatility, lower return (and thus a much lower Sharpe Ratio), higher Downside Risk and Maximum Drawdown and a lower Maximum Gain, all of which translate into negative Alpha [2]. This, of course, is backward-looking, but it serves to demonstrate that the UK has not fared well in global terms, either on relative performance or on a risk-adjusted basis.

Of course, if Brexit was the only potential fly in the ointment it may be possible to argue that a resolution thereof would clear the way for a decent rally, at least in relative terms – but the implosion in support for the Conservatives ahead of the European elections, as “Leavers” opt to switch to the Brexit Party, leaves the door open for Labour (and thus Jeremy Corbyn). In 2015, when we first discussed his potential victory, it seemed a long shot, but the odds of Labour winning the next General Election are now better than 50:50, for the first time in a long while [3]. Assuming that Corbyn retains the Labour leadership, he would be PM and whatever could be said of him, “market-friendly” is not one of them, as could be seen recently in plans announced to re-acquire the energy sector infrastructure, with compensation to be in the form of UK government bonds. They have also indicated that they would seek to regain control over the water industry, the transport network and have made clear that higher taxes (only on the “wealthy” mind), are coming down the track too. All this will put pressure on Sterling (which is already teetering a little), back below $1.27, down from nearly $1.32 at the start of May. Signs that the current Prime Minister is not much longer for this political world mean uncertainty and that, for traders, means selling the pound, which they are duly doing.

What does this imply for UK Biased portfolios? That sticking with overweight UK holdings may be sub-optimal for a considerable period of time. Given the extent of the returns lag versus the rest of the World, it might be tempting to assume some sort of “rebound” is due, but that could have (and has been) said over at least the last year and possibly longer. It is true that a weaker currency tends to help the global UK firms (as c.70% of the revenue from the FTSE All Share is generated internationally for example), but it makes global investors nervous, (as they invest primarily on a currency basis first and then on an asset class basis thereafter). It also means that the existing UK holdings of foreigners fall in value, which often inhibits new investment. There will come a point when overseas investors decide that the UK represents a “bargain”, but when that might be is impossible to know. In the meantime, the UK’s lack of exposure to Technology (and its over-exposure to Banks, Commodities, etc.) may act as a brake on performance, particularly if the US Dollar remains strong.

So we remain convinced that a more Global portfolio is the solution here. Global diversification is the best way to mitigate risk because valuations are not the final word in investing and certainly not in the short term, as shares are a claim on a very long term stream of cash flows attributable to shareholders. They are often a potential indication of risk – sometimes a market, such as the UK, is “cheap” for a reason. In this instance, the intersection between UK politics and economics has created more uncertainty than investors have been used to hitherto. Thus, returns need to rise to compensate investors for those risks and this can mean potentially long periods of relative underperformance. We have witnessed this ourselves (first hand) in the Value factor via EBI portfolios and the timescale to recovery can be excruciatingly long. It is unlikely to be different for UK equities either.

[1] In passing one might note that some of them date back to a year ago, whilst others, from November 2018 have repeated the assertion. The headlines have become less strident of late, possibly due to the fact that over both time frames the All Share Index has lagged the World ex-UK Index, (rising by just 1.17% since May 2018).

[2] All of this highlights the relative but not absolute nature of the return; it is still gaining, just considerably less than alternative investment locations.

[3] The odds of the next UK Prime Minister are skewed by the reality that Theresa May will likely be replaced by a Conservative MP before the advent of an election, so does not reflect the true odds of a Corbyn victory.