From time to time both ourselves and our clients get contacted by journalists looking for quotes and views on the debate surrounding Active and Passive Investing, which (usually) revolve around asking us what our investment approach is, or how we use the two types of investment strategies for our portfolios. So, in order to formalise our response and to give clients an idea of how to respond should they receive similar enquiries, we decided to put our views down “officially”, in the form of a Q&A.

The main belief system that separates Active from Passive investors concerns the extent to which markets can be said to be “efficient”. Whilst few would argue that the “Strong” Efficient Markets Hypothesis is correct, (as there would be no “bubbles” as per 2000 and 2007 if it were true), it is perfectly possible to argue that markets may be “macro” efficient whilst being “micro” inefficient. That is, while individual assets may be mispriced, markets overall rarely are (or rarely for long). It is not, as Cliff Asness has noted, necessary for a large number of actors to set efficient prices – merely those that do, do so accurately. If they did not, opportunities for active managers would arise – but either they have not arisen, or active managers are unable to take advantage of them. Either way, active managers are becoming redundant- in some cases, literally.

As we cleave towards the view that markets are basically efficient, we would favour Passive investing, as it is a low-cost, low-risk way of collecting market returns as they occur. Those that believe the opposite would prefer, (presumably), to take their chances with active fund managers. This of course means paying their fees, whilst not knowing what sort of return one is going to get.

The simple arithmetic is that, in aggregate, passive gets market return minus relatively low costs, whereas active investors get market return minus higher costs, plus or minus the active managers’ “Alpha”. It is the latter unknown that makes active investing inherently riskier, as it is impossible to discern, ex-ante, who those winners and losers will be.

Active managers appear at present to be going through what psychologists describe as the 5 stages of grief, (in this case, for the loss of their fee income). Initially, when passive investing come to prominence, there was widespread denial of its relevance, followed shortly thereafter by angry condemnation (one is “settling for mediocrity”, Indexing is “worse than Marxism” and other assorted special pleading by those dependent on fund trading for their living); we now appear to be at the “bargaining” stage. Having reached this point, active investors (and commentators) are now opine that the two can co-exist, whilst accepting that Index/Passive investing has beaten Active over the last 10 years – it is a shame that they didn’t forewarn us of this in 2008-09, when Index investing came into its own, but then active managers don’t know the future either! We still have depression (presumably caused by a realisation that the reduction in fee income is permanent), and finally acceptance to go before the process is over.

Below is an illustration of some of the type of questions we get asked.

Q: How does a Core/Satellite approach work in the context of Active and Passive investing?

The basic idea is that one uses Index funds to track “Core” markets (Developed markets in both equities and bonds), whilst employing active funds at the periphery, to take advantage of perceived “inefficiencies” in less developed markets. Of course, some do occur, but not for any meaningful length of time, as the competition for Alpha is fierce and, in the context of a highly intelligent, focussed and well informed marketplace (even in EM), it gets competed away very quickly. The simple truth is that for every active “winner” there is a corresponding “loser” in relative terms at least and past performance is no guide to successfully picking them out. As costs are involved, it is a negative-sum game, such that both winning AND losing fund investors must pay the fees associated with this investment process. The industry regulator tells us that past performance is no guide to future returns, but there is ONE indicator that accurately performs this function – investment costs. The less one pays, the more of the market return one gets to keep.

Q: Does Active work better than Passive in unpredictable markets?

This is a derivative of the first question. The first thing one might ask is which markets are “predictable”?

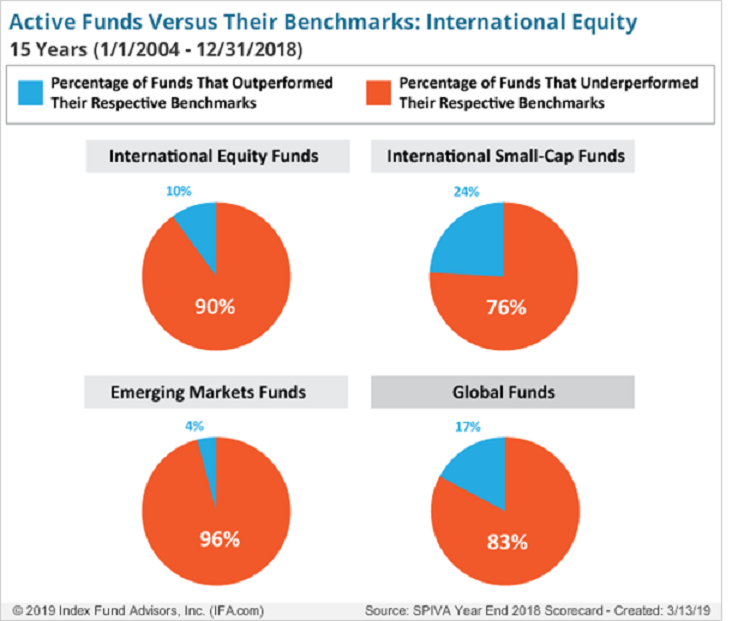

SPIVA reports on a quarterly basis on the relative performance of active versus Indices and shows the failure of active management in graphical detail. As the chart below shows, even in Emerging Markets, the SPIVA reports consistently show that active managers fail to beat their benchmark targets (96% of them in EM). Not over 1, 3 or 5 years, but 15- this is not a one-off event.

Small Cap shares are, likewise, often cited as an “inefficient” marketplace, as a result of liquidity issues as much as anything else. A recent FT article (29/11/19-subscription needed), cited an S&P Global dataset that suggested 60% of US actively managed funds beat their respective Indices in the 12 months to June 2019. Though the writer did concede that it was a “rare” victory – the 10-year average number of funds outperforming their Indices was 3%. That 60% of professional fund managers managed it once in 10 years tells us quite a lot; that there is a 10% chance of beating the Index in a given year, some might prefer to toss a coin, as this ratio appears suspiciously close to chance.

We have not seen any evidence that active managers do better the more unpredictable that markets become, in fact, to the contrary on a risk-adjusted basis. Their problem, to us, is that a highly volatile market does not improve their chances of success (howsoever defined), but merely increases the range of returns across the active manager sub-set. The shibboleth that active managers do better in volatile or bearish markets has repeatedly been demolished in the experience of recent years, (with the most recent example being this article from last month). Vanguard have also refuted this myth on multiple occasions. It might seem plausible that they can sell, hold cash and re-invest at lower, presumably better prices, but they don’t seem to actually do any of this. Instead, they end up chasing prices higher once markets have bottomed, having only sold, at best, near the end of the previous downtrend. It is a fact of human existence that this should be the case (as we are all pattern-seeking primates at heart), but we see no reason to indulge it, as it does not benefit our clients. Judging by the long term trend of assets leaving active managers to invest passively, we are by no means alone.

Q: What are the pros and Cons of using Passive investing in different markets for particular exposures?

Given the advances in the technology and process of Index tracking, it is now possible to match the returns of a market benchmark almost perfectly. Index re-balancing USED to be a problem as traders “front-ran” index changes to try to profit from those changes in advance, but it appears that the likes of Vanguard, iShares and others have mastered this problem to the point that they have very little effect on Index tracking error. To use Emerging Markets again, the MSCI Index has over 1200 stocks, spread across 26 Emerging Market nations and the Tracking Error over 5 years for the Vanguard EM Stock Index fund is just 1.64% (according to Financial Analytics data). This is on an Index with an annualised volatility of 16.5% (which equates to a weekly volatility of 2.29%) – so the fund exhibits less tracking error in one year than the Index moves in a week! Thus, we would disagree with the notion that Indices anywhere are hugely inefficient, (though there are differing degrees of efficiency), but mostly these are due to market factors over which investors have little control. The inability to short-sell (or borrow shares to do so) can have an effect on pricing efficiency, but in most cases major market Indices do allow both of these, which serves to enhance the workings of the marketplace. As we do not invest in relatively illiquid markets (Junk bonds, CDOs or Private Equity) this is not an issue for us; while it may be possible, (in theory), to exploit these pricing “errors”, the degree to which this is achievable, once the costs of doing so are taken into account, suggests that risk-adjusted returns are not material and probably not worth attempting.

Q: What is the best way to use Active and Passive funds together?

At EBI Portfolios, we do not exclusively use Passive/Index finds, but not due to a belief in active management per se- in some areas/sectors there are no viable passive solutions available. Fund houses only issue new Index products where there is perceived interest and so in some areas (Value shares for example), there is little competition due to the reality that investors do not currently demand these funds. As such, in UK Value for example, we use Dimensional’s offering despite the fact they are not truly passive investors, preferring instead to act as liquidity providers (buying when others are selling and vice versa) to obtain at or below market prices (and in theory higher returns). For them, Index tracking is not the primary aim, so their trading “style” can be seen as a hybrid between active and passive investing. Trading costs are thus constrained, but at the price of higher overall tracking error. This is not ideal for us but as there are few/no alternatives, we have to live with this by-product of their approach to markets. Sometimes it yields excess returns, at other times it does not, much as one might expect by investing actively.

Q: Are there any staple funds that we always use in Active and Passive portfolios?

We use broadly the same (Index) funds across our suite of portfolios, though in some instances there are practical limitations to using identical ones. In the case of our World portfolios, we use ETFs as they provide exposure to Investment “factors” such as Momentum, which cannot be bought via mutual funds. The differences between Vantage UK, Global and World portfolios is often seen in differing cost versions of essentially the same market exposures. The difference between Vantage UK and Vantage Global is one of UK equity exposure. Legacy clients have often preferred to be invested in countries (and company’s) that they know, but this is changing, as the putative currency risk of investing overseas has been largely dealt with, either by hedging overseas bond returns to sterling (by buying £ hedged funds), or by the reality that UK (and foreign firms) that invest outside their domestic currency regime routinely hedge the currency risk themselves (and at a far better rate than we can do ourselves internally at EBI). If the investment horizon is sufficiently long, currencies, being mean-reverting assets often “wash themselves” out over time in any event.

Q: Will the rise of shareholder activism make active managers more relevant?

The proposition is that active managers are better able to instigate change within corporations than can passive funds, as they can force change on recalcitrant managements for the wider benefit of society. This has particular relevance for ESG-related corporate governance issues. The argument goes that active investors can sell the shares of firms that refuse to institute change and refuse to buy into others who fail their ESG screening “tests” for example, unlike passive funds which must remain in a share until such time that it ceases to be part of the Index that they are tracking. So, Index funds are “forced” to stay invested and thus cannot do anything it is alleged. But this is a rather specious argument.

Firstly, will selling a company’s shares make any practical difference? After all, active managers selling shares is part of what they do, otherwise they would not be active managers. BP, for example trades millions of shares each and every day – would senior management care if a fund or a number of funds exited the share? Probably not, unless the resultant share price decline was sufficiently large to affect the company’s cost of capital. One does not need to be overly cynical with regard to managements’ inherent motivations to imagine that a vote against their next remuneration award would be infinitely more “influential” on their attitude towards ESG policies or any other issue than any amount of shareholder resolutions exhorting them to behave more responsibly. It is not possible to vote on this if one has already sold the shares, as active managers would have already done under this line of reasoning.

Evidence strongly supports the superiority of Index investing over active management and it is unclear why one would want to compromise over this, it is not a matter of “fairness”, but one of utility. The aim of investing is to maximise returns thus ensuring retirement goals are met, and not to ensure that all fund managers get an equal proportion of the assets available to manage.

No one, in real life, buys products that do not meet a perceived need or are not of demonstrable value to the purchaser. An industry that does not have what one wants/needs at an appropriate price will go out of business, as the UK high street is discovering. So it is with active managers, the most extreme version of which is the absolute return (a.k.a. hedge fund). In recent weeks, there have been a number of high profile Hedge fund closures (see here and here), which, ironically may have spurred the recent sharp rise in equity prices in the US (as their short positions need to be closed, leading others to buy them to “front-run” the liquidation process). As the chart below shows, there have been more hedge fund closures than openings for nearly a year and this process shows no signs of relenting.

We wrote a blog piece in early 2016 wondering about the future of hedge funds (and by extension active managers in general); it is now clear that their demise has been a process rather than an event. But it is looking more and more certain to continue to its inevitable conclusion. Some (mostly active managers), are of the belief that higher market volatility (which is a euphemism for a bear market), will save them – they should be careful what they wish for. It is much more likely to finish them off for good…

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.