This guy goes to a psychiatrist and says, “Doc, my brother’s crazy; he thinks he’s a chicken.” And the doctor says, “Well, why don’t you turn him in?” The guy says, “I would, but I need the eggs.” – Woody Allen (Annie Hall).

At the end of March, we discussed the implications of a yield curve inversion for both markets and the US – and thus the world- economy, concluding that acting on this “signal” might be premature (at least). Thus far, markets have refused to go along with the economic gloom, with the MSCI World Index currently just 1% below the all-time highs of August last year. Having inverted almost across the board, US bonds are now seeing a small reversal as rate cut expectations have been reduced a little. The FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) minutes last week suggested a “holding pattern” has now been adopted, with neither rate cuts nor rises on the cards – “patience” is now the watchword.

So, unless the equity market has got it completely wrong, a recession is deemed less likely than before. But what about the opposite? In the spirit of contrarianism, we must consider that inflation could be about to rise again from what looks like to have been a dormant state? There is no sign of it at present, whether one looks at the US or the UK (below), though whether this data corresponds to anyone’s real-world experience is another matter entirely.

![Linechartimage[1]](https://ebip.co.uk/uploads/blog_post_content/t1555408312/linechartimage%5B1%5D.png)

Global Central banks have been very successful in generating inflation – but in asset prices rather than in the economy, in the process fueling massive income inequality, which inevitably leads to a backlash amongst those who perceive a system “rigged” against them; which is where we get to a potential reversal in the current trends. In our Blog What Wrong with Buybacks?, we noted the rise of demands for curbs on Share re-purchases and prior to that, we noted the rise in support for Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which appears to gain acceptance amongst US Democratic politicians. It is clearly increasing in popularity, and it is here that the risk of higher (consumer price) inflation arises. Last week, Nancy Pelosi, (the US House Speaker) announced that she wanted to meet President Trump to discuss $1-2 trillion in infrastructure spending. As no details of where this money was coming from was forthcoming, it is safe to assume that the money will be “found” (i.e. borrowed) from somewhere.

There are two principal causes of Inflation in goods prices – demand pull and cost-push [1], the former essentially being about growth and latter about shortages and as a consequence, the response from the authorities to the two would normally be different. Looking at the policy prescriptions suggested above (and the continued sub-par growth forecasts in major economic areas), one would expect to see the latter be the major factor in creating (and sustaining) the growth of inflation. The growth of debt over the last 20 years does imply that demand may not be the initial cause of the problem, but the policies advocated by supporters of MMT could certainly have an effect, as rising government spending, in a world where capital expenditures have not kept pace with the rate of share buy-backs (and do not look likely to do so this year either), could easily lead to supply shortages as spare capacity struggles to keep up with state-sponsored demand.

As mentioned in previous blog pieces, equities would be considered a good “hedge” against the inflation risk associated with higher, (usually wasteful), state spending, but that assumes that they have pricing power – that is, can they maintain market share if they raise prices to consumers? For some, (e,g, Netflix?) this may be possible, but for others (Apple’s iPhone at $1000 currently) it may not. For some, such as utility companies here in the UK, they may not get the choice – governments are already cracking down on their ability to raise prices and one can easily foresee some sort of quasi-price controls being introduced should “headline” inflation start to rise.

The last comparable period was in the 1970s when the inflation genie appeared to escape the bottle; it was not a great decade by any standards, with the FT30 (at the time, the UK Equity Index benchmark), falling by 73% in the two years up to the end of 1974, and the 5 year return for the FTSE All Share to 1975 was a wretched -43%, made even worse in real terms by the high inflation that pertained at that point.

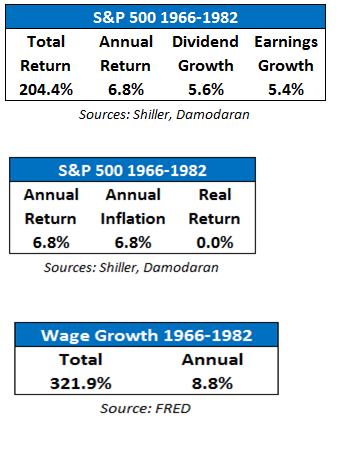

Interestingly, the US equities fared better, as seen below, the S&P 500 returned 6.8% annualised in the 16 years to 1982, whilst the Dow went sideways over the same time period. Adjusted for inflation, however, the real return on the S&P was zero- for 16 years! In the same period, US bonds lost 40%.

The situation that prevailed in this period was almost the exact opposite to what is occurring now – two Oil price shocks (in 1973 and again in 1979), which led to high inflation and low asset prices, whereas we now have high asset prices and low wages/inflation. It could be said that the 1970s reflected “cost-push” inflation (wages grew by 8.8% at the same time as oil prices rocketed) and should the same thing happen again, it would require policies to dampen demand – given the extreme aversion of Central Banks to raising interest rates beyond current levels, this may not happen quickly enough (or at all) to halt price rises, leading very quickly to rates of inflation that we have become VERY unaccustomed to in recent years.

Could this situation recur? Of course, particularly in light of the political developments outlined above, though there is no certainty as to the success of the Democrats against Trump in the next election, or that of Corbyn vis-a-vis the Conservatives over here – but it is inconceivable, given the changing political zeitgeist, that any political party will now choose to fight an election on “austerity”, meaning that the choice for the electorate will be between differing levels of extra spending, rather than a binary choice or whether or not to spend more.

Events will NOT pan out exactly as in the 1970s, but there are similarities that bear a resemblance to those days. A successful investment strategy (i.e. as complete a diversification as is possible), allows for the possibility of unforeseen events, which includes the possibility of investor over-reaction to those events. The only things that investors CAN control is the level of savings and their responses to the situation they find themselves in. It is not necessarily the likelihood of negative “shocks” that derails the investor but the effect of those shocks; and most of all, how they respond…

[1] In reality, the two are interlinked, such that one may feed through into the other.

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.