“Currency Manipulation is what Bertrand Russell called an “emotive conjugation” and Bernard Woolley called an “irregular verb”:

* I am cutting interest rates

* You are trying to achieve a competitive devaluation

* He/she/it is manipulating their currency to obtain an unfair advantage”. – John Kemp (Analyst)

We have written from time to time about currency moves (here and more recently here), mainly with regard to the US Dollar, but things rarely stand still in investment markets and a new trend appears to be emerging – that of currency debasement, as each nation attempts to lower the value of their domestic unit to better improve their export performance. In a low-growth world, each government believes that the solution is to increase the competitiveness of their export goods, whilst making it more expensive for its residents to buy imports. This is known as Mercantilism – et Voila, the trade balance improves and the economy grows. There are several ways to achieve this end, and both the ECB (in Europe) and the BoJ (in Japan) use one or more of them almost continuously [1]; the recent announcement of Christine Lagarde’s appointment as the Head of the European Central Bank has led investors to buy yet more (negatively yielding) European sovereign bonds (as they expect further money printing/interest rate cuts to come). More QE from Europe might lead to a more direct US response, potentially including direct FX intervention by the US Treasury to sell the Dollar (as some on Wall Street are now speculating on). According to Bloomberg, Trump has asked two potential Federal Reserve candidates for their views on the Dollar – if they wish to pass said interview they will need to suggest ways to weaken it.

No country will ever admit it is doing so, and they have refrained from publicly accusing each other of practicing it but competitive devaluation enters all of their thinking, especially when trying to boost economic growth in a world teetering on the brink of recession. But recent tweets from Donald Trump, (never one to adhere to a convention) appear to have broken the mutual ceasefire – a tweet from 3/7/19 makes the point in his unique style:

“China and Europe playing big currency manipulation game and pumping money into their system in order to compete with the USA. We should MATCH, or continue being the dummies who sit back and politely watch as other countries continue to play their games – as they have for many years!”

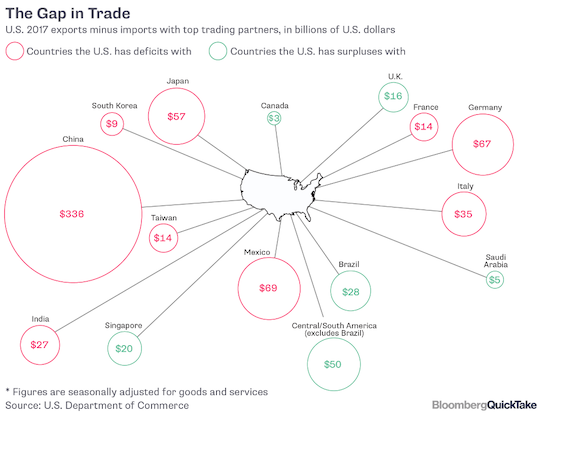

The US appears to be moving away from its “Strong Dollar” policy, as the pre-eminent plank of its economic thinking. This can be put alongside Trump’s constant attacks on the Fed for having “too high” interest rates and paves the way for a sustained Dollar decline. Or does it? As the US/China trade war has worn on, the Chinese have allowed their currency (the Yuan) to fall, in effect offsetting the effect of tariffs, blunting the intended impact on Chinese exports. The chart below shows the trade gap between the US and various nations as of 2017. It is clear that Europe, Mexico, Japan, and India (in addition to China) are very much in the firing line and have all felt the “Trump effect”, either in tweet form or more directly.

The irony of all this is that the whole process is ultimately futile – it can only work if everyone else does nothing about it (a). Each currency quotation is a relative price (Yen versus the Dollar or Sterling versus the Euro, etc.) and they can’t ALL drop; if the Dollar were to fall against the Yen, for example, the BoJ would simply employ one of the methods described above to push their currency back down again, leaving the relative prices of the two at the same position as before [2]. According to Bloomberg this week, negative yielding global debt (Government and Corporate) now totals $13.4 trillion (up almost $2.2 trillion in the past month) [3]. The only reason to buy this debt (for which the investor pays the issuer) is an expectation of a stronger currency, which offsets the negative yield of the asset. But the competitive devaluation policies almost guarantee that this cannot happen, which makes one wonder what these buyers are thinking…

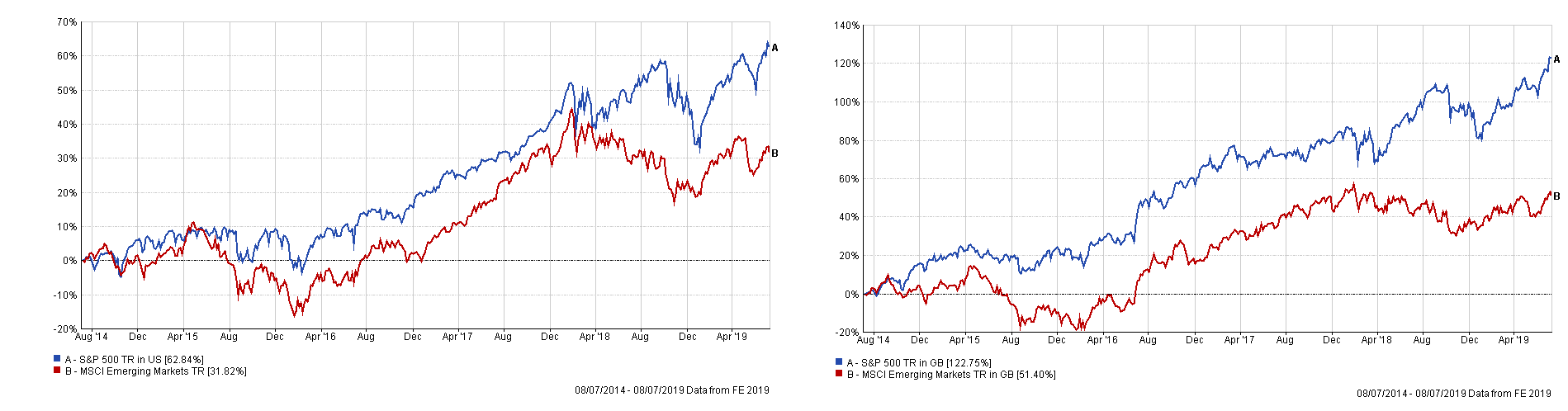

What does this mean for investors? At EBI, all our overseas bond funds are Sterling hedged and thus see no effect from this phenomenon, but equity funds CAN experience an impact. As a rule of thumb, the weaker ones investing base currency, (Sterling for most of us), the more positive the return (and vice versa). The charts below show returns of two equity markets in both Local currency terms and that of Sterling; the pound’s weakness over the last 5 years has boosted returns significantly. This is not guaranteed of course, but if we assume that competitive devaluations have no net effect (in the long term as per the argument above a), the translation effect (converting an overseas investment into one’s domestic currency), will not likely be longstanding or material. Should Sterling start to rise anew, Governor Carney will be under great pressure to react in the appropriate fashion.

As we have also said many times, the Dollar remains the World’s Reserve Currency (via the dominance of the Dollar in the Global payments system) and there is as of yet no real alternative to it as a store of value. Whenever trouble strikes, investors head for the US Dollar as they know it is a safe and liquid market. Donald Trump may not like it but he may as well get used to it. There have been concerted attempts by China and Russia, as well as Iran, to by-pass the Dollar in recent years, but so far they have come to nothing. In one sense Trump may hope that they succeed, but there would be consequences for US asset markets. Luckily for him, there is no sign that this will change in the medium term.

[1] One outlier might be the Bank of England, who has done relatively little in this regard, but the slow-motion car crash that is Brexit may be doing most of the work for them. The continuous stream of warnings about higher UK rates to come has not (and likely will not) come to pass for the same reason as with every other nation. Nobody wants the world’s strongest currency. The Swiss Central Bank has accumulated a vast US equity portfolio as part of its attempts to avoid this fate.

[2] Except that this is not quite true. The consumer would be worse off as the cost of imported goods rise; but as they have no lobbying power, they are for all intents and purposes ignored.

[3] This article highlights the extent of this phenomenon in Europe in both multiple countries and bond maturities.