Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem.

No more things should be presumed to exist than are absolutely necessary. (Occam’s Razor).

One of the defining trends of recent years has been the rise of ETF’s /Index funds which have taken hold over the course of the period post the Financial Crisis. There have been a proliferation of “Factors”, or possibilities of Alpha generation, many of which turn out to be either useless (i.e. they never worked) or redundant (they don’t now). This study suggests that there have been 59 new Factors “discovered ” between 2010 and 2012 alone!

So, what is a “Factor”? It consists of a set of rules or characteristics that produce above expected returns or systematically reduce portfolio risk, thereby creating portfolios that are close to or on the Efficient Frontier, as defined by Harry Markowitz in his concept of Modern Portfolio Theory. The main ones (i.e. those that have stood the test of time and practicality), are Beta (i.e the market), Value, Size, Momentum, Profitability, Term (Bonds have a higher return the longer the maturity), and Carry ( which is the idea that a return can be generated from the yield that the asset generates-the higher the yield, the higher the return, assuming prices do not change)[2].

How does one begin to decide which Factor to employ? To be useful, they must meet specific criteria, or else risk being found (after the investment event) wanting.

1) They must have delivered a premium to market returns and have explanatory power (in other words they should be statistically responsible for the returns generated in some meaningful way).

2) They must be persistent, across both time and different markets (there is little point in using a factor that only works in Asia for example), and thus pervasive.

3) They should be robust to various definitions (e.g for Value stocks, some use Price/Book, others use Price to earnings, still others Price to Cash Flow). Thus, the returns are not dependent on one specific variable.

4) They must be investable; if the trading costs wipe out the returns, the factor cannot work in practice.

5) They should be intuitive; are there logical (or behavioral ) reasons for the Factor’s existence and more importantly, its continuation?

Of course, it isn’t quite that straightforward (is it ever?); for a start, return premiums are as unreliable as a vote-chasing politician. Long periods (which in the case of Value recently, has seemed like eons) can pass with no signs of the premium in question. It is therefore important to both maintain one’s investment discipline AND to diversify across these factors (though not so much as to dilute their individual effect). One way to consider this is to take into account the cycle length of the factors one is looking to invest in. Helpfully, Northern Trust has provided some research on this subject, in which they advocate the factor alignment of one’s portfolio with one’s investment horizon, such that the investor does not risk the possible forced liquidation of the portfolio prior to the completion of the Factor’s cycle of return (the Premium Maturity problem) [3]. According to NT, the Size premium has a cycle length of of c.106 months (8.8 years) in contrast to Value (47 months) and Momentum (39 months). Ignoring the other factors mentioned, a portfolio allocation to these factors needs to be long term in nature, with the longer the investment horizon, the greater the allocation to Size and Value. As the horizon, shortens, one should allocate more towards the shorter cycle factors ( which they identify as Min Vol, High Yield (Carry) and to a lesser extent, Momentum) [4].

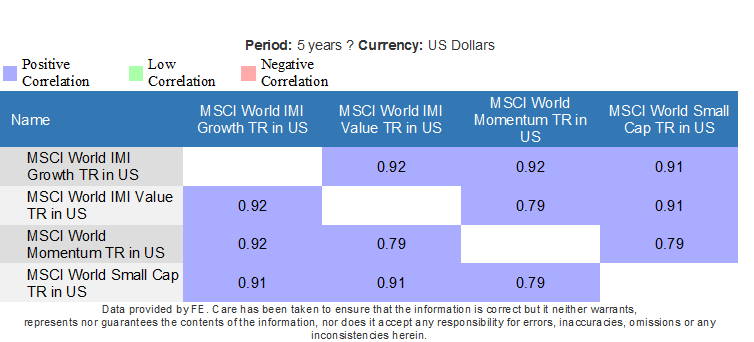

It is also important to increase diversification by choosing Factors that have low or negative correlations between them, to smooth out Factor cycles. The lower the correlation of two factors the better the fit between them in a portfolio. Using the table below as an example (though it is not necessarily long enough to serve as an exact template and is presented as an illustration only), it is clear that the lowest correlations are between Value and Momentum and Momentum and Small. (That the correlations are relatively high is a function of the liquidity tsunami unleashed by Global Central Banks over the last decade or so which may have distorted the relationship between the differing factors). Combining Value and Momentum and Small with Momentum can create diversification benefits, though in the case of Value and Momentum, they have similar cycle lengths, so are in sync with each other, such that they could peak or trough at roughly the same time. It is therefore necessary to adjust relative weightings accordingly to take this into account, as portfolio returns will most likely be disproportionately affected by the returns of the shortest premium maturity. (So, one would be relatively overweight Value or Small versus Momentum).

As can be seen from the above, there are a number of difficulties in efficiently and effectively implementing this strategy; but it is clearly a more efficient way of capturing return premiums and avoids the need to stock pick on a continual basis. Doing so actually creates a tilt within the portfolio that the manager may not be aware of, via his or her own investment biases (or preferences). During the course of our Q2 research for clients, one often finds that portfolios have done well (or badly) primarily as a result of exposures that may have excessively influenced performance (for good or ill). The most recent example is the recent “Income” investing fad, which has served investors extremely well since 2009, but which has lagged the FTSE All Share Index in the last 2 years. A fund manager (or investor) going into this sector over the last 2 years has seen under performance which is not necessarily related to poor stock picking (though that is often present too). It is possible that these fund managers were simply performing in line with their factor exposures, which wax and wane over time, which in turn may have little to do with their ability. ( It has been well documented that Pension funds (and individual investors) tend to hire fund managers after strong returns and then fire them again when they lag). Neil Woodford’s Equity Income fund, for example, has beaten the IA Equity Income sector by 3% per annum since June 2014 but lagged by 1.5% p.a. in the last 2 years. It would be hard to argue that he has suddenly become a lousy fund manager (though he may never have been as good as some have suggested!).

For us at EBI, Factor investing is an extension of what we have already been doing. We have long had “tilts” towards those parts of the market that appear to exhibit premiums over and above that of the market return. (Value and Small Cap are the most prominent examples). Notwithstanding the issues raised above, it seems the most efficient way to invest for the long term buy and hold investor. As long as the portfolio is appropriately diversified and the investor can live with the uncertainty as to the timing of factor performance, we should pick up the returns commensurate with the risks being taken. Absent a crystal ball, that is just about all an investor can do.

[1]. We now live in a highly computerised world. Where once it took days to produce results supporting an investment thesis, it is now possible to “crunch the numbers” in seconds, enabling analysts to justify all manner of ideas and strategies. Unfortunately, this has led to all manner of spurious correlations; given enough computing power, and enough time, one can find back-tested data to support almost any strategy, but they are just as likely to be the consequence of randomness or selection bias. For every one factor that is deemed viable, how many have been discarded in the process of its discovery? A cynic might ask if the main purpose of all this “Factor Production” is for Academic tenure or Investment product purposes rather than for the benefit of investors.

As has been said, if you torture the data long enough, it will confess to anything. Hence the emergence of the “Factor Zoo”, a term coined by Professor John Cochrane in his presidential address to the American Finance Association in 2011, a veritable plethora of characteristics that mostly tell the investor nothing about future returns.

[2] Opinions vary on this of course. Put two analysts in a room and you are likely to get three views! At EBI, we employ several of these factors, in our Vantage portfolios as well as the Varius funds, though not always via ETF’s and not always directly; (for example, we have holdings in Small Cap stocks, but in Varius we also own the Vanguard Global Liquidity ETF. The latter is a proxy for Small Caps, (as Small Caps tend to be less liquid than their larger cap brethren and this is a cheaper way to gain the same exposure).

[3] Defined as the length of time an investor would expect to hold an asset to capture the excess return from that Factor.

[4] NT calculate that the Standard Deviation of these cycles is approximately HALF the length of the cycle itself, implying that one needs an investment horizon roughly twice that of the Cycle to reduce the risk of duration mismatch. They believe that the relative weightings are unaffected by Expected Return and Volatility assumptions (though this is slightly more debatable).

Disclaimer

We do not accept any liability for any loss or damage which is incurred from you acting or not acting as a result of reading any of our publications. You acknowledge that you use the information we provide at your own risk.

Our publications do not offer investment advice and nothing in them should be construed as investment advice. Our publications provide information and education for financial advisers who have the relevant expertise to make investment decisions without advice and is not intended for individual investors.

The information we publish has been obtained from or is based on sources that we believe to be accurate and complete. Where the information consists of pricing or performance data, the data contained therein has been obtained from company reports, financial reporting services, periodicals, and other sources believed reliable. Although reasonable care has been taken, we cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any information we publish. Any opinions that we publish may be wrong and may change at any time. You should always carry out your own independent verification of facts and data before making any investment decisions.

The price of shares and investments and the income derived from them can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the amount they invested.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance.