“What You Gain On The Swings, You Lose On The Roundabouts.” – Robert Jordan (US Author), from his book “The Path of Daggers”.

The subject of currencies has started to crop up quite frequently of late (and we have been at least partly responsible for this). Clients have been getting more interested in the effects of FX moves on portfolio returns, but it seems that there are still some misapprehensions regarding what effect the choice of the different share classes of the same fund has on returns. So we will try to show the effects by way of a simple example. In this instance, we shall compare the investment fortunes of an investor in Vanguard’s S&P 500 Index fund, buying the fund in Euros, or alternatively in US Dollars; the principles apply across all funds where non-base currency investments are made, but I have used Euros and Dollars as an example as there is no directly comparable GBP share class visible on their website.

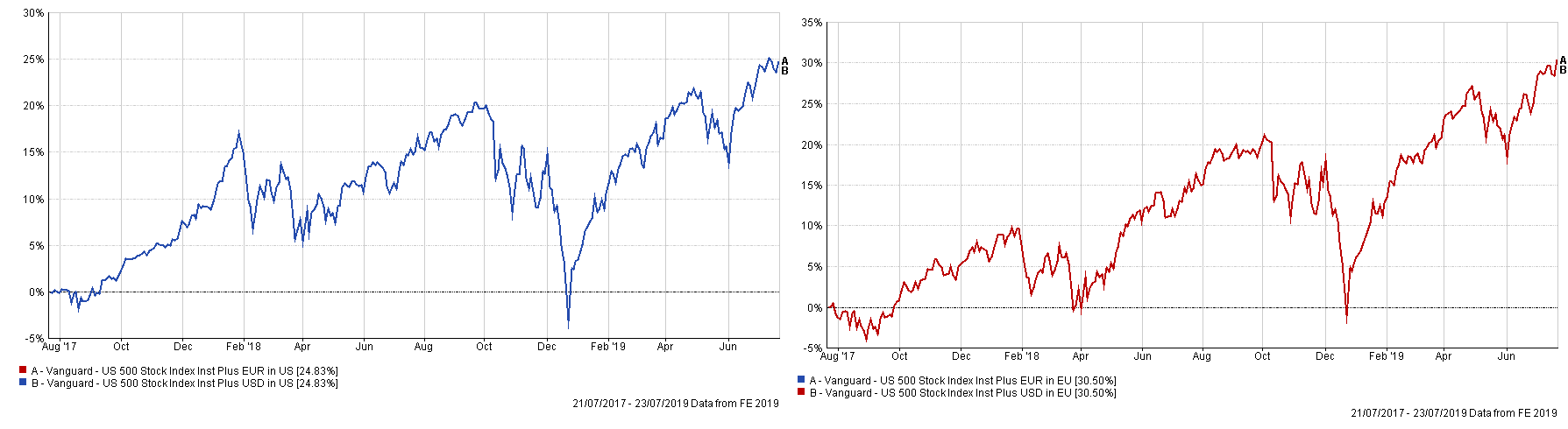

As you can see from the Factsheets, the fund’s holdings are exactly the same, whether you are invested in the USD fund, the Euro version. Some believe that they can buy the USD class to benefit from an expected Euro decline (or vice versa), but this is not true. As the chart shows, it makes no difference! The returns are exactly the same regardless of FX rate changes or market moves – see below [1] for how one can demonstrate this.

This reality is due to the fact that if they were different, there would be an arbitrage opportunity, for risk-free profits. It thus makes no difference to the investor whether they convert their Euro capital into US Dollars and give it to the fund manager in USD or give it to the fund manager (who then converts it themselves into US Dollars) to make the investment. Given that fund managers can get far better exchange rates than are available to the rest of us, it makes sense to “outsource” this process to them, but if they are doing their job correctly it will not affect the overall net return, regardless of in which class one invests in.

The basic reason is that one still has to invest in the currency of the investment asset (USD in the case of the S&P 500) – so regardless of one’s initial base currency, the investor is exposed to movements in the value of the underlying asset’s currency.

The overall return to an investment in a non-base currency is equal to the market return, plus or minus the change in the currency exchange rate over the investment horizon and the currency one starts from has no effect on the overall return, as it is the investment currency (not the investor’s base currency) that determines the investment performance.

The situation is somewhat more nuanced in other regions – for example, in Emerging Markets, the predominant investment currency is US Dollars (and many individual companies can be accessed via ADRs (American Depository Receipts, or Global Depository Receipts), which enable fund managers to own shares in EM countries without needing, for example, to be members of the relevant exchange. In this instance, there will still be some need to invest in the Malaysian Ringgit or the Saudi Riyal for example, but ADRs/GDRs can reduce this requirement substantially. But the essential FX exposure remains (US Dollars), for the same reasons as above.

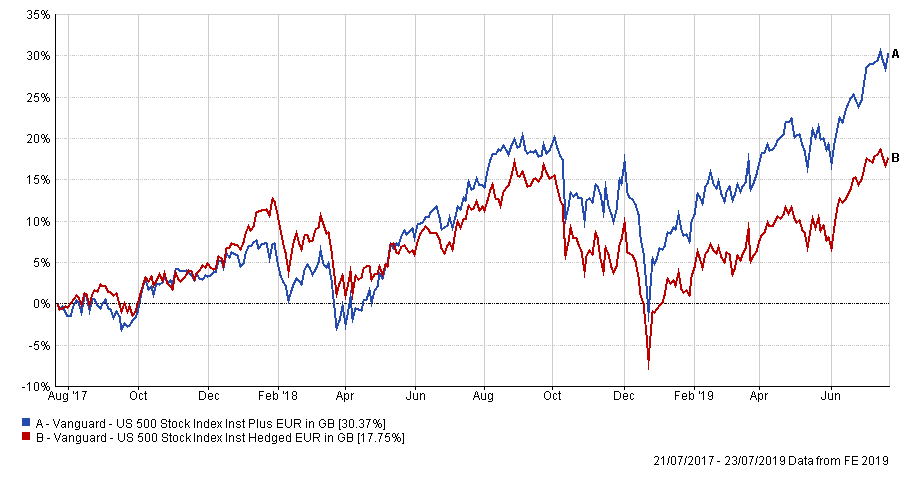

Of course, one could buy a share class which is hedged to one currency or another; this effectively “locks in” an FX rate (the value at the point of investing), for the duration of the investment horizon. This can work, but only if one has the correct view on the direction of FX rates. As the chart below highlights, hedging the S&P 500 to Euros worked well up to the start of 2018, as the Euro rose to a high of €1.25 against the Dollar, but since then, the fall back to the €1.12 level has led to severe underperformance relative to the unhedged version as the hedged fund has not had the benefit of the rise in the value of the US Dollar vis-a-vis the Euro, (around 11%). The lag is even greater than the actual rise in the Dollar due to the costs of implementing the hedge, (which due to the interest rate differentials between the Dollar and the Euro is currently very expensive to maintain) – which is another reason why EBI does not hedge overseas equity exposures.

In bonds, however, the situation is rather different – we DO hedge FX risk, but NOT for the reasons previously noted; we use hedged bond funds because (generally speaking) FX volatility is higher than bond market volatility, (unlike with equities), such that it is very possible for exchange rate moves to overwhelm the price effect on bonds, so that one could lose money on bonds not due to interest rates / credit risks, etc. but solely due to FX changes. As bonds are in our portfolios as a risk-reducing investment, by NOT hedging we would thereby increase overall risks, with no compensatory benefits. As bond yields go sub-terranean on a global scale, these risks get even greater.

Of course, by hedging out one’s FX exposures one may outperform an un-hedged version of the same fund, but weighing up all the factors, we see no value in “taking a view” on currencies either way. As we have no expertise in this arena, it does not make much sense to attempt to finesse the FX market, so we do not do so. If one does have a strong opinion on the direction of a currency, it can be employed by choosing to hedge (or not to hedge). But this is a battle we do not wish to fight.

[1] Let us assume that we invest €50,000 into the fund – at an exchange rate of €1.12 to the Dollar, this equates to a USD investment of €50,000 x 1.12 = $56,000. Assuming a 10% market rise and an unchanged FX rate (a condition which we shall relax later), this gives a US Dollar value of $61,600. But this then needs to be converted back into Euros, which gives us a value of €55,000, which is the same as a 10% rise in the initial Euro investment of €50,000.

But FX rates rarely stay the same, so we shall do the same, but assuming a rise in the Euro to €1.15 at the point of selling the investment and assume no change in market values. €50,000 invested in the S&P 500 would give an initial investment of $56,000 but when converted back Euros this would be worth €48,696 – this (loss) would be exactly equal to the loss in the value of the US Dollar over the period (1.15/1.12= -2.609%).

Let us now assume both a 5% market rise AND a 5% rise in the value of the Euro (to €1.176). An investment in the Dollar class would yield an initial value of €50,000 x1.12 = $56,000, being invested in the Index. This then rises by 5% to give a total of $58,800, but once converted back into Euros at the lower rate (for the Dollar) of €1.176 gives a return of €50,000, exactly where we started. In both cases, the rise of the Euro has completely offset the gain from the US market.

These calculations can be done in the same manner using Sterling as the base currency with no change in the effect. Trying to “avoid” Sterling depreciation by investing in Dollars or Euros etc. is both futile AND counterproductive.